Potential stormwater hotspots

Potential Stormwater Hotspots (PSHs) are activities or practices that have the potential to produce relatively high levels of stormwater pollutants. Designation as a PSH does not imply that a site is a hotspot, but rather that the potential to generate high pollutant runoff loads or concentrations exists. PSHs include locations where there is a potential risk for spills, leaks, or illicit discharges. Stormwater hotspots may also be areas which produce higher concentrations of pollutants than normally found in urban runoff. Because stormwater hotspots are found in a variety of land uses, there is no common pollutant for any type of hotspot. Instead the pollutants tend to be a unique mixture of pollutants (CWP, 2005). Hotspots can be classified as Regulated, subject to state or federal permits, or Unregulated. In Minnesota Regulated hotspots are subject to the NPDES Multi-Sector General Permit for Industrial Activity, and/or local ordinances.

Contents

Pollutant generating operations and activities

The potential for hotspots is related to the activities on the site more than the land use or category of operation. The table below summarizes the most common pollutants generated at stormwater hotspots based on common operations at a site. These operations are discussed in greater detail below.

Pollutants of Concern from Operations (adapted from CWP, 2005).

Link to this table.

| Pollutant of concern | Vehicle operations | Waste management | Site maintenance practices | Outdoor materials | Landscaping |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrients | X | X | X | ||

| Pesticides | X | X | |||

| Solvents | X | X | |||

| Fuels | X | ||||

| Oil and grease | X | X | |||

| Toxic chemicals | X | X | |||

| Sediment | X | X | X | X | |

| Road salt | X | X | |||

| Bacteria | X | X | |||

| Trace metals | X | X | |||

| Hydrocarbons | X | X |

Vehicle operations

Vehicle operations include maintenance, repair, recycling, fueling, washing, and long-term parking. Vehicle operations can be a significant source of trace metals, oil, grease, and hydrocarbons, and are the first operations inspected during a hotspot source investigation. Vehicle maintenance and repair operations often produce waste oil, fluids and other hazardous products, particularly if work areas are connected to the storm drain system. Routing protective rooftop runoff through a fueling area has become a common practice in Minnesota; simple re-routing of runoff away from a potential fuel wash-off location could eliminate this from the hotspot list. Examples of pollutant-generating activities associated with vehicle operations include the following.

- Improper disposal of fluids down shop and storm drains

- Spilled fuel, leaks and drips from wrecked vehicles

- Hosing of outdoor work areas

- Wash water from cleaning

- Uncovered outdoor storage of liquids/oils/batteries/spills

- Pollutant wash-off from parking lots

Outdoor materials

Improper handling or storage of materials outdoors can create stormwater problems. Techniques for properly handling materials outdoors include inventorying the type and hazard level of materials at the site, examining loading and unloading areas to see if materials are exposed to rainfall and/or are connected to the storm drain system, and investigating any materials stored outdoors that could potentially be exposed to rainfall or runoff. Public and private road salt and sand storage areas are of particular concern. Examples of pollutant-generating activities associated with outdoor materials include the following.

- Spills at loading areas

- Hosing/washing of loading areas into shop or storm drains

- Wash-off of uncovered bulk materials and liquids stored outside, of particular concern in MN are road salt storage areas

- Leaks and spills

Waste management

Every business generates waste as part of its daily operations, most of which is temporarily stored at the site pending disposal. The manner in which waste products are stored and disposed of at a site, particularly in relation to the storm drain system, determine the likelihood of becoming a hotspot. In some sites, simple practices such as dumpster management can reduce pollutants, whereas other sites may require more sophisticated spill prevention and response plans. Examples of pollutant-generating activities associated with waste management include the following.

- Spills and leaks of fluids

- Dumping into storm drains

- Leaking dumpsters

- Wash-off of dumpster spillage

- Accumulation of particulate deposits

Physical plant maintenance

Plant maintenance relates to practices used to clean, maintain or repair the physical plant, which includes the building, outdoor work areas and parking lots. Routine cleaning and maintenance practices can cause runoff of sediment, nutrients, paints, and solvents from the site. Sanding, painting, power-washing, and resealing or resurfacing roofs or parking lots are activities that can result in increased pollutant loading or concentrations, especially when performed near storm drains. Examples of pollutant-generating activities associated with plant maintenance include the following.

- Discharges from power washing and steam cleaning

- Wash-off of fine particles from painting/sandblasting operations

- Rinse water and wash water discharges during cleanup

- Temporary outdoor storage

- Runoff from degreasing and re-surfacing

Turf and landscaping

Many commercial, institutional and municipal sites hire contractors to maintain turf and landscaping, apply fertilizers or pesticides, and provide irrigation. Current landscaping practices should be thoroughly evaluated at each site to determine whether they are generating runoff of nutrients, pesticides, organic carbon, or are producing non-target irrigation flows. Examples of pollutant-generating activities associated with turf and landscaping include the following.

- Non-target irrigation

- Runoff of nutrients and pesticides

- Deposition and subsequent washoff of soil and organic matter on impervious surfaces

Determining if a PSH is a hotspot

As stated previously, the designation of PSH does not mean a site is a hotspot, only that activities have the potential to generate higher pollution runoff loads or concentrations compared to the land uses in which they occur. When designing a stormwater management system at these sites, it is important to determine if the PSH is an actual hotspot. If it is a hotspot, additional stormwater management controls may be needed. A recommended process for determining whether a PSH is a hotspot is as follows.

- Step 1: Consider where the activities take place. If all activities using hazardous materials occur inside a building and no materials can be tracked outside, then the site is not a hotspot. The various activities involving hazardous materials should be monitored at regularly scheduled intervals to ensure that nothing changes that would cause the hazardous materials to come in contact with stormwater runoff.

- Step 2: Review the Stormwater Pollution Prevention Plan/Program (SWPPP), if present. Sites subject to NPDES requirements through the Industrial Multi-Sector Permit or the MS4 Municipal General Permit may have created SWPPPs that guide the operations and housekeeping at sites where the potential exists for increased concentrations of certain pollutants in the runoff.

- Step 3: Conduct a site inspection. The Center for Watershed Protection (CWP) has developed inspection forms that can be used to record physical operations and observations at a site to assess whether the site should be designated as a hotspot. For sites with a SWPPP, the inspection should include whether the site is operated in compliance with the requirements in the SWPPP. The CWP form includes an overall assessment of whether to designate the site as a hotspot. To access the CWP information go to this link and find Urban Subwatershed Restoration Manual Series Manual 8: Pollution Source Control Practices to open the document as a pdf. Hotspot prevention profile sheets are found on pages 109-158. A discussion of stormwater hotspots is found on pages 13-24.

- Step 4: Sample collection and analysis. Further analysis may be required to determine if the PSH is a hotspot. Samples of the stormwater runoff at the site should be collected and analyzed for the pollutants of concern. Samples need to be collected from the runoff that is in contact with the waste to ensure that there is accurate site characterization. There is no specific criteria for concluding a location is a stormwater hotspot, although concentrations in runoff may be compared to water quality criteria to make this determination. See surface water quality standards or drinking water standards. Recommendations for design adjustments are included in the following section.

The U.S. EPA developed a hotspot inspection checklist that can be used to score a site to determine the likelihood that it is a stormwater hotspot.

General guidelines for managing stormwater at a PSH

Even if a PSH is determined to not be a hotspot, some additional considerations are needed for stormwater management. Runoff management at PSHs and hotspots should be linked to the pollutant(s) of greatest concern. Understanding the pollutants potentially generated by a site operation provides designers with important information on proper selection, siting, design, and maintenance of nonstructural (e.g., source control or pollution prevention) and structural practices that will be most effective at the site. Active inspection and monitoring of the site activities is required to ensure that a PSH does not become a hotspot. The table below provides a general summary of pollutants of concern from different operations. For a more detailed list of operations and associated pollutants, see Table 7 on page 18 of the CWP report Pollution Source Control Practices, Version 2.0. To access the CWP information go to this link and find Urban Subwatershed Restoration Manual Series Manual 8: Pollution Source Control Practices to open the document as a pdf.

Pollutants of Concern from Operations (adapted from CWP, 2005).

Link to this table.

| Pollutant of concern | Vehicle operations | Waste management | Site maintenance practices | Outdoor materials | Landscaping |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrients | X | X | X | ||

| Pesticides | X | X | |||

| Solvents | X | X | |||

| Fuels | X | ||||

| Oil and grease | X | X | |||

| Toxic chemicals | X | X | |||

| Sediment | X | X | X | X | |

| Road salt | X | X | |||

| Bacteria | X | X | |||

| Trace metals | X | X | |||

| Hydrocarbons | X | X |

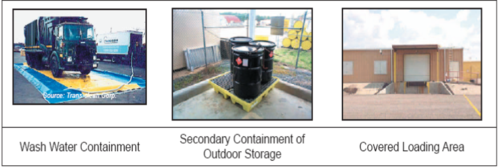

Non-structural approaches such as sweeping, indoor storage, employee training, and frequent trash collection should be employed as much as possible. Not only will they prevent stormwater generation, they are also the most cost effective approach. To implement these effectively, it is necessary to have a thorough understanding of a site and the respective areas of the site where specific operations will occur. Hogland, et al. (2003) suggest the following principles for design at PSHs and hotspots.

- Develop detailed mapping of the different areas of the site along with associated planned activities and the preliminary drainage design. Identify PSHs on the site (i.e. areas where pollutants may potentially be released) and attempt to eliminate or minimize the likelihood there will be a release. Within PSHs,

- prevent or confine drips and spills, and

- enclose or cover pollutant generating activity areas and regularly provide cleanup of these areas.

- Provide spill prevention and clean-up equipment at strategic locations on site.

- Provide pre-treatment and spill containment measures such as catch basins and inserts, oil-water separators, etc.

- Strategically locate slopes and separation berms to prevent co-mingling of the runoff that does and does not come in contact with the pollutant of concern.

- Retain and reuse stormwater for irrigation, wash down water, or other onsite uses.

- Maintain equipment to minimize leaks.

- Train and educate employees, management and customers.

Meeting the design intent of the non-structural practices above typically involves simple and low-cost measures to address routine operations at a site. For example, the non-structural design components for a vehicle maintenance operation might involve the use of drip pans under vehicles, tarps covering disabled vehicles, dry cleanup methods for spills, proper disposal of used fluids, and covering and secondary containment for any outdoor storage areas.

Each of these practices also requires employee training and strong management commitment. In most cases, these practices save time and money, reduce liability and do not greatly interfere with normal operations. A more complete summary of 15 basic pollution prevention practices applied at PSH operations is provided in the table below.

Summary of common pollution prevention practices for PSH operations (Source: Scheuler et al., 2004).

Link to this table

| PSH operation | Profile sheeta | Pollution prevention practices |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle maintenance and repair | H-1 | Drip pans, tarps, dry clean-up methods for spills, cover outdoor storage areas, secondary containment, discharge washwater to sanitary system,proper disposal of used fluids, disconnect storm drains, automatic shutoff nozzles, signs, employee training, spill response plans |

| Vehicle fueling | H-2 | |

| Vehicle washing | H-3 | |

| Vehicle storage | H-4 | |

| Loading and unloading | H-5 | Cover loading areas, secondary containment, storm drain disconnection or treatment, inventory control, dry cleaning methods, employee training |

| Outdoor storage | H-6 | |

| Spill prevention and response | H-7 | Inventory materials, employee training, spill planning, spill clean up materials, dumpster management, disconnect from storm drain or treat. Liquid separation/containment |

| Dumpster management | H-8 | |

| Building repair and remodeling | H-9 | Temporary covers/tarps, contractor training, proper cleanup and disposal procedures, keep wash and rinse-water from storm drain, dry cleaning methods |

| Building maintenance | H-10 | |

| parking lot maintenance | H-11 | |

| Turf management | H-12 | Integrated pest management, reduce non-target irrigation, careful applications, proper disposal of landscaping waste, avoid leaf blowing and hosing to storm drain |

| Landscaping/grounds care | H-13 | |

| Swimming pool discharges | H-14 | Varies, depending on the unique hotspot operation |

| Other unique hotspots | H-15 |

aDue to the volume of material, the reader is referred to Scheuler et al. (2004) to see the profile sheets. Each profile sheet explains how the practice influences water quality and lists the type of PSH operation where it is normally applied. The sheets also identify the primary people at the hotspot operation that need to be trained in pollution prevention. Next, each sheet reviews important feasibility and implementation considerations and summarizes available cost data. Each profile sheet concludes with a directory of the best available internet resources and training materials for the pollution prevention practice. To access this information go to Urban Subwatershed Restoration Manual Series Manual 8: Pollution Source Control Practices. Hotspot prevention profile sheets are found on pages 109-158. A discussion of stormwater hotspots is found on pages 13-24.

It should be noted that the profile sheets developed by Scheuler et al. (2004) are written primarily from the perspective that the site(s) in question is an existing site and pollution prevention measures are recommended as a retrofit approach. Designers of new sites, however, can still use the guidance effectively.

Wright et al. (2004) provide a detailed description of the rapid field assessment protocol for identifying PSHs and the appropriate pollution prevention practices for the activities causing pollution. The protocol is known as the Unified Subwatershed and Site reconnaissance (USSR) and the PSH assessment is called a Hotspot Site Investigation. These methods are not directly applicable to greenfield development or redevelopment situations; however, they have significant application for NPDES Phase II communities that are working towards compliance with Minimum Control Measures 1, 2, 3, and 6 (public education and outreach, public participation/involvement, illicit discharge detection and elimination, and pollution prevention/good housekeeping, respectively).

After considering the non-structural elements to incorporate into a site, designers need to assess what structural practices will provide the greatest pollutant loading reductions for targeted pollutants, if the pollutant is present in the runoff, given site constraints. Details on BMP design and performance can be found within web pages for individual BMPs.

Caution, the literature contains a large amount of information concerning BMP removal capability for a range of common pollutants. When using this information, be aware of the assumptions and limitations of the data. Some of this data has been compiled for this Manual. Targeted pollutants are phosphorus, total suspended solids, total nitrogen, hydrocarbons, bacteria, and metals.

The receiving water designation or watershed classification often drives the criteria and associated practices that are acceptable for use. However, at PSHs there is a set of general guidelines to consider when designing structural stormwater management systems. The following should be carefully considered by designers when specifying and siting practices at PSHs, specifically when it is determined that the site is an actual hotspot.

- Pretreatment. This includes properly sizing sediment trapping features such as forebays and sedimentation chambers; incorporating appropriate proprietary and nonproprietary practices for spill control purposes and treatment redundancy; oversizing pretreatment features for infiltration facilities such as swales, filter strips, and level spreaders; and ensuring full site stabilization before bringing practices online. If infiltration is to be utilized, appropriate site and conveyance designs are needed and the pretreatment BMP size should be increased or design redundancies included.

- If pollutant generating activities exist on a site, runoff from these areas should be treated separately from other runoff at the site. BMPs such as bioretention, constructed ponds, and constructed wetlands that receive runoff from pollutant generating activities should be designed with the necessary features to minimize the chance of groundwater contamination. This includes using impermeable liners. The use of ponds and wetlands without liners should also be avoided where water tables are shallow and the practice would likely intercept the water table. Bioretention BMPs can be designed and constructed with adjusted media content and media depth according to the Bioretention Design Guidelines to accommodate the pollutants of concern.

- Consider use of liners, underdrains, or comparable safeguards against infiltration when runoff exceeds target concentrations.

- Locate practices offline and minimize offsite run-on with appropriate diversions.

- Establish rigorous maintenance and inspection schedules for practices receiving the runoff from the hotspot areas of concern.

Infiltration guidance

Infiltration practices require scrutiny prior to implementation at a PSH. Preventing the introduction of contaminated runoff to groundwater is an essential consideration in developing effective stormwater management plans at PSHs. This is because

- ground water contamination is hard to detect immediately and therefore can persist over long periods of time prior to any mitigation;

- there is an immediate public health threat associated with ground water contamination in areas where ground water is the primary drinking water source, and

- mitigation, when needed, is often difficult and is usually very expensive.

With appropriate site and conveyance design it is possible to incorporate infiltration into many sites to treat areas sufficiently separated from pollutant generating activities. Most design modifications are simple and in the form of enhanced pretreatment, over-design, or design redundancies. Others are added features that limit the likelihood of groundwater recharge. For example, practice groups such as bioretention, ponds and wetlands that receive runoff from pollutant generating activities should be designed with the necessary features to minimize the chance of groundwater contamination. This includes using impermeable liners. The use of ponds and wetlands without liners should also be avoided where water tables are shallow and the practice would likely intercept the water table. Where uncertainty is present, designers should avoid infiltration practices.

The table below provides general infiltration guidelines associated with operational areas of concern.

Infiltration guidelines for potential stormwater hotspots.

Link to this table.

| Operational area | Potential infiltration guidelines |

|---|---|

| Landscaping | Infiltration is acceptable provided there is no run-on or co-mingling from higher pollutant loading areas and appropriate pretreatment is provided for the specified practice. Chemical management is needed to limit the amount of fertilizer and pesticides. |

| Downspouts | Infiltration is acceptable provided there is no run-on or co-mingling from higher pollutant loading areas, there is no polluting exhaust from a vent or stack deposits on the rooftop, and there is appropriate pretreatment provided for the specific practice. |

| Vehicle operations | Infiltration is acceptable with the following provisions:

|

| Waste management and outdoor material storage1 | Infiltration is typically not recommended but may be utilized if spill prevention and containment measures are in place, such as catch basin inserts and oil and grit separators; or if redundant treatment is provided, such as filtering prior to infiltration. Infiltration should be prohibited in areas of exposed salt and mixed sand/salt storage and processing. |

| Loading docks1 | Infiltration is typically not recommended but may be utilized if spill prevention and containment measures are in place, such as catch basin inserts and oil and grit separators; or if redundant treatment is provided, such as filtering prior to infiltration. |

| Vehicle fueling1 | Infiltration is not allowed under the CGP. |

| Highways1 | Infiltration is possible where enhanced pretreatment is provided. Where highways are within source water protection areas and other sensitive watersheds, additional measures should be in place such as spill prevention and containment measures (e.g., non-clogging catch basin inserts and oil and grit separators. |

1indicates operational area with likelihood of having higher pollutant loadings

Links

- Stormwater Pollution Prevention Guidance - Vehicle Maintenance and Repair, Fueling, Washing or Storage Loading and Unloading, Outdoor Storage. Maryland Department of the Environment Stormwater Pollution Prevention Guidance. 2013.

- Hotspot inspection form. U.S. EPA

Related pages

- Overview of stormwater infiltration

- Pre-treatment considerations for stormwater infiltration

- BMPs for stormwater infiltration

- Pollutant fate and transport in stormwater infiltration systems

- Surface water and groundwater quality impacts from stormwater infiltration

- Stormwater infiltration and groundwater mounding

- Stormwater infiltration and setback (separation) distances

- Karst

- Shallow soils and shallow depth to bedrock

- Shallow groundwater

- Soils with low infiltration capacity

- Potential stormwater hotspots

- Stormwater and wellhead protection

- Stormwater infiltrations and contaminated soils and groundwater

- Decision tools for stormwater infiltration

- Stormwater infiltration research needs

- References for stormwater infiltration

This page was last edited on 2 February 2023, at 20:49.