Difference between revisions of "Green stormwater infrastructure - planning case studies"

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

==Rochester GSI Planning Case Study: 1st Avenue and 3rd Street Pocket Park, Rochester, MN== | ==Rochester GSI Planning Case Study: 1st Avenue and 3rd Street Pocket Park, Rochester, MN== | ||

| + | [[File:Rochester pocket park.png|300px|thumb|alt=location of pocket park in Rochester|<font size=3>Location of pocket park in downtown Rochester</font size>]] | ||

| + | |||

'''Brief overview of project''' | '''Brief overview of project''' | ||

| − | In 2019, the City of Rochester (the “City”) completed construction on a pocket park in downtown Rochester that includes green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) such as rain gardens | + | In 2019, the City of Rochester (the “City”) completed construction on a pocket park in downtown Rochester that includes green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) such as rain gardens (bioretention) and permeable pavers. These GSI practices capture and treat runoff from a nearby parking ramp and street corridor, and reduce the pollutant load contribution to the [https://www.pca.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/wq-iw7-45e.pdf South Fork Zumbro River], which is impaired for bacteria and turbidity. This project, [https://www.rochestermn.gov/home/showpublisheddocument/18349/636584481519930000 funded by an EPA 319 Grant], emphasizes environmental education with an informational placard and an interactive push-button water pump that allows visitors to “play” with the GSI by bubbling water through the infiltration basin. The park also boasts public art – a limestone bubbling fountain – from Rochester-native artist Jenna Didier and benches for visitors to enjoy the green space. This park and its many social, economic, environmental, and aesthetic co-benefits paved the way for future GSI projects in the City. |

'''Planning Process Highlights''' | '''Planning Process Highlights''' | ||

| − | The City’s Public Works Department led the planning for the 1st avenue and 3rd street pocket park, starting circa 2015 with the development of GIS tools to help site GSI in Rochester’s challenging environment that includes ultra-urban neighborhoods and an underlying | + | The City’s Public Works Department led the planning for the 1st avenue and 3rd street [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pocket_park pocket park], starting circa 2015 with the development of Geographic Information System (GIS) tools to help site GSI in Rochester’s challenging environment that includes <span title="Highly urban and ultra-urban settings have a large percentage of impermeable surface and typically have limited space to install surface BMPs. An example would be a downtown area."> '''ultra-urban'''</span> neighborhoods and an underlying <span title="Karst is a landscape formed by the dissolution of a layer or layers of soluble bedrock. The bedrock is usually carbonate rock such as limestone or dolomite but the dissolution has also been documented in weathering resistant rock, such as quartz. The dissolution of the rocks occurs due to the reaction of the rock with acidic water. Rainfall is already slightly acidic due to the absorption of carbon dioxide (CO2), and becomes more so as it passes through the subsurface and picks up even more CO2. Cracks and fissures form as the runoff passes through the subsurface and reacts with the rocks. These cracks and fissures grow, creating larger passages, caves, and may even form sinkholes as more and more acidic water infiltrates into the subsurface."> [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Karst '''Karst''']</span> geology. Around this time, the US EPA also announced their 319 Grant Solicitations to fund projects that will reduce nonpoint source (NPS) pollution. The City used the GIS tools to identify potential locations for GSI that could be funded under the 319 Grant Program. Initially the City sought to partner with private developers on a new development project. Interest by private developers was limited however, because some of the grant requirements – such as including an educational component – went above and beyond what the developers were willing to invest at the time. The City subsequently pivoted to identify public facilities that could be retrofitted to include GSI. In 2018, the City performed a feasibility analysis to create a pocket park with GSI to capture and treat the runoff from a parking ramp and adjacent roadway. With the entire project footprint on public right-of-way, there was no need to include private partners. The public works department largely led this effort on its own with some input and collaboration from the City’s parks department. The public works Department also leads the maintenance of the GSI system, primarily due to the specialty maintenance required by the water pumps in the park. |

To qualify for the 319 grant, the City was required to develop a Nine Element Watershed Based Plan (the “Nine Element Plan”), which is a detailed plan of how the proposed GSI will address (reduce) nonpoint source pollution. Quantifying the expected load reductions from the GSI was important to the Nine Element Plan as well as the City since these potential reductions have a direct beneficial impact to the South Fork Zumbro River, which is located downstream of the project and is impaired for turbidity and bacteria. In addition to estimating load reductions, the Nine Element Plan also requires an educational component. To address this requirement, the City designed the pocket park as an inviting place for public enjoyment, using benches, an informational placard, and an interactive water feature to draw in the public and provide educational information on stormwater. The interactive water feature is a central piece of the pocket park and includes a push-button water pump that bubbles water through the infiltration basin. While not required by the grant, the City also included public art as part of the pocket park – a limestone fountain that serves as a statement piece to highlight the connection between the local limestone geology and the waterways that flow through the City of Rochester. | To qualify for the 319 grant, the City was required to develop a Nine Element Watershed Based Plan (the “Nine Element Plan”), which is a detailed plan of how the proposed GSI will address (reduce) nonpoint source pollution. Quantifying the expected load reductions from the GSI was important to the Nine Element Plan as well as the City since these potential reductions have a direct beneficial impact to the South Fork Zumbro River, which is located downstream of the project and is impaired for turbidity and bacteria. In addition to estimating load reductions, the Nine Element Plan also requires an educational component. To address this requirement, the City designed the pocket park as an inviting place for public enjoyment, using benches, an informational placard, and an interactive water feature to draw in the public and provide educational information on stormwater. The interactive water feature is a central piece of the pocket park and includes a push-button water pump that bubbles water through the infiltration basin. While not required by the grant, the City also included public art as part of the pocket park – a limestone fountain that serves as a statement piece to highlight the connection between the local limestone geology and the waterways that flow through the City of Rochester. | ||

| Line 105: | Line 107: | ||

Funding the project was a big part of the planning process and presented some challenges. The 319 grant funding allowed the City to pursue this project, but the projected construction costs exceeded the grant funds. The Public Works Department had to go to the City Council to make the case for the project and request more money to complete the project. The Public Works Department highlighted the project’s many co-benefits, including the public space amenity and art installation by a local artist to obtain the additional funds from City Council. | Funding the project was a big part of the planning process and presented some challenges. The 319 grant funding allowed the City to pursue this project, but the projected construction costs exceeded the grant funds. The Public Works Department had to go to the City Council to make the case for the project and request more money to complete the project. The Public Works Department highlighted the project’s many co-benefits, including the public space amenity and art installation by a local artist to obtain the additional funds from City Council. | ||

| − | Overall, the project timeline spanned approximately 5 years, starting with preliminary planning and tool development in 2015, grant application and feasibility analysis in 2016-2017, design in 2018, and construction starting in 2018 and finishing in 2019. | + | Overall, the project timeline spanned approximately 5 years, starting with preliminary planning and tool development in 2015, grant application and feasibility analysis in 2016-2017, design in 2018, and construction starting in 2018 and finishing in 2019. |

| − | This project, along with recent stormwater ordinance changes driven by MS4 permit requirements, has paved the way for future implementation of GSI. The new ordinance serves as a catalyst for GSI implementation while the pocket park serves as a GSI demonstration site to show GSI can be done in the City of Rochester. | + | |

| + | This project, along with recent stormwater ordinance changes driven by <span title="A municipal separate storm sewer system (MS4) is a means of transportation, individually or in a system, (e.g. roads with drainage systems, municipal streets, catch basins, curbs, gutters, ditches, man-made channels, storm drains, etc.) that are: owned or operated by a public entity (e.g. cities, townships, counties, military bases, hospitals, prison complexes, highway departments, universities, etc.) with jurisdiction over disposal of sewage, industrial wastes, stormwater, or other wastes. This includes special districts under State law (sewer, flood control, or drainage districts, etc.), an authorized Indian tribal organization, or a designated and approved management agency under section 208 of the Clean Water Act; designed or used for collecting or transporting stormwater; not a combined sewer; and not part of a publicly owned treatment works."> '''MS4'''</span> (Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System) permit requirements, has paved the way for future implementation of GSI. The new ordinance serves as a catalyst for GSI implementation while the pocket park serves as a GSI demonstration site to show GSI can be done in the City of Rochester. | ||

'''Additional Information:''' | '''Additional Information:''' | ||

Latest revision as of 16:42, 3 January 2023

This page summarizes three case studies on planning for green stormwater infrastructure projects. The cases studies cover a variety of topics and scenarios.

- Highland Bridge project, Capitol Region Watershed District and City of St. Paul, MN: Highlights a large development site project incorporating GSI features

- Duluth, MN GSI planning tool, highlights development of and use of a tool for identifying and prioritizing GSI projects

- Rochester, MN, highlights a project completed in downtown in which social factors were incorporated into the design and project

Highland Bridge, Capitol Region Watershed District and City of St. Paul, MN

Project Summary

The Highland Bridge project (formerly Ford Redevelopment Site) is the redevelopment of roughly 122 acres of land along the Mississippi River in Saint Paul, MN that was previously home to Ford’s Twin Cities Assembly Plant. This redevelopment project converted the industrial land to residential and commercial space, including 55 acres of parks, open spaces, and waterways. This project is unique in that it uses a non-conventional stormwater management system called the “Hidden Falls Headwaters approach”. In this novel approach, stormwater from the site is captured and treated by green stormwater infrastructure (GSI), stored in concrete chambers, and eventually filtered and delivered to the Hidden Falls Creek and the site’s central water feature, a meandering open water channel surrounded by green space. This approach also daylighted and re-established the historic Hidden Falls Creek which had been previously buried and paved over.

Planning Highlights

The planning process for the Highland Bridge project was extensive and decades in the making. Early planning conversations included Ford, the City of St. Paul, and the Capitol Region Watershed District (CRWD). The initial planning group grew over time to include the city’s public works department and finance department as well as the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) and the surrounding community.

MPCA became involved in the planning process to provide expertise and oversight of the remediation of the legacy soil contamination from the manufacturing materials at the old Ford plant. This remediation was an essential requirement to rezone the site from industrial land to residential and commercial space. The remediation and rezoning process provided a challenging hurdle in the planning process but was necessary to execute the overall vision of an aesthetic and safe green space amidst the mixed-used development.

Another key component of the Highland Bridge project was stakeholder engagement. The public was heavily involved in the planning process, particularly in the Ford Site Zoning and Public Realm Master Plan, whose development included over 45 public meetings. The early public engagement meetings included education on traditional stormwater management mechanisms, the green stormwater infrastructure solutions considered, and the potential benefits of the GSI. Later public meetings included opportunities for the community to provide input to the project vision. The stakeholder engagement also included an online platform for the public to access project information and meeting materials, and provide feedback.This allowed more of the public to engage with the project even when not able to attend the public forums.

The planning team was able to “make the case” for integrating GSI in the project by doing a triple bottom line analysis that showed the economic, environmental, and social benefits of the Hidden Falls Headwaters approach compared to a more traditional stormwater management approach. The analysis put a monetary value to the social and environmental benefits to ultimately quantify the full value of the project to the community and showed that the project outperformed traditional stormwater management by a factor of 2. The public was largely in favor of the redevelopment and the proposed GSI as it promised more housing, a public water feature surrounded by green space, reduced traffic concerns, and other public amenities.

The city finance department played a key role in the planning process to successfully seek and obtain public funding for the project. The redevelopment project was supported through public funding with some contribution from private investments. A key component to the financing of the project was the creation and adoption of a green infrastructure overlay district ordinance (RES 20-672). This ordinance requires developers to pay a one time connection fee and an annual O&M (operation and maintenance) fee that will support the continued maintenance of the stormwater management system.

Project Timeline

Concept planning began in 2007 with the formation of the Ford Site Planning Task Force. The first phase of the planning process and work involved visioning studies, remediation, and a stormwater study. The second phase of work started in 2015 and kicked off the more detailed planning process working towards a master plan. In 2017, The Ford Site Zoning and Public Realm Master Plan was adopted by the Saint Paul CIty Council. Construction on the Hidden Falls Headwaters stormwater management system began in 2020 and was largely completed by late 2021. Development on the remainder of the site began in late 2021 and buildout is estimated to take 10-12 years.

Social benefits An important component of this project was the incorporation of social aspects into the design. Some examples are briefly discussed below.

- Affordable housing: The Highland Bridge Master Plan requires 20% of all housing units to be affordable, with a mix of rental and owner-occupied housing options. At final build out, Highland Bridge will include approximately 763 new units affordable to households earning 60% or less of Area Median Income (AMI), with half of these affordable to extremely low-income households earning 30% or less of AMI. For more information, link here.

- Recreation: Although development is on-going and will continue for several years, the Master Plan includes several recreational features, including small parks, the Central Water feature, and access to adjacent trails and recreational opportunities (e.g. River Road trail system, Hidden Falls Park, Minneapolis parks and trails across the Mississippi River). For more information, link here. From the City of St. Paul's website: "Highland Bridge will introduce four new City Parks as part of over 55 acres of greenspace, right of way, and open space. The Civic Square and Civic Plaza are suited to host a variety of activities and events, and will anchor a vibrant mixed-use corridor. The central water feature will be the project’s marque public space, surrounded by native plantings, bike and pedestrian paths, and perfect for a selfie or your favorite outdoor activity.".

- Retail: The City of St. Paul hopes the project’s retail will include restaurants, fitness, lifestyle and destination entertainment in addition to its first confirmed retail tenant, Lunds & Byerlys. Retail partners will be announced on highlandbridge.com. Check the City's News page to read the latest, or check out the Office & Retail page.

- Transportation: The development site is conveniently located along two major bus lines, one of which is a rapid line. These lines connect to downtown St. Paul, the Green Light Rail Line, and the Blue Light Rail Line.

- Environmental sustainability: The development sites includes a variety of sustainable initiatives related to energy, stormwater, building design, transportation, and water. For more information link here.

Quick facts

- Location: St. Paul, MN

- Owner: Ryan Companies

- Designer: Barr Engineering

- Year of completion: Stormwater management components largely completed in late 2022

- Design features:

- Shared stacked green stormwater infrastructure

- Central water feature consisting of a meandering channel

- Re-establishment of Hidden Falls Creek

- Green space

- Pretreatment Features

- Bioretention : 4.8 ac

- Retention pond: 2.4 ac

- Total Drainage Area: 169 ac

- Total Construction Cost: projected cost 13.7M

- Documented Maintenance Practices:

- Central Stormwater Easement requires that the city of St. Paul:

- Maintain treatment efficiency of the central stormwater feature

- Remove sediment, trash, debris, blockage, and pollutant buildup in the central stormwater feature and pre-treatment as well as sediment removal from any upstream structures

- Weed and noxious species control

- Central Stormwater Easement requires that the city of St. Paul:

- Pollutant Removal

- Total suspended solids: 28 tons/yr

- Phosphorus: 147 lbs/yr

- The GSI is estimated to reduce total stormwater solids by 94% and phosphorus by 75% compared to pre-development conditions.

- Is the Site Publicly Accessible: Yes

- Notable Challenges: Remediation and rezoning

- Co-Benefits

- Added green space

- Recreational opportunities

- Restoration of historic creek

- Spaces atop GSI for parks, amphitheater, meeting space etc.

- Economically favorable compared to conventional stormwater management

Duluth GSI planning case study: Strategic Green Infrastructure Siting Tool

Brief Overview of Duluth’s Unique GSI Challenges

The City of Duluth (the “City”) faces unique challenges to green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) implementation. Hydrologic soil group D soils dominate the landscape of Duluth and provide little infiltration of rain or storm water into the ground – a large obstacle to infiltration-based GI practices. The groundwater table can also be fairly high in Duluth, and bedrock is often shallow or exposed which creates further challenges to implementing successful GSI projects in this area. Despite these challenges, Duluth is committed to implementing GSI where feasible. To that end, the City developed a GSI siting tool to help identify potentially suitable locations for GSI implementation. This tool takes into consideration the challenging landscape and identifies locations suitable for GSI implementation and has helped the City’s GSI planning efforts by increasing the number of potentially suitable GSI locations that otherwise would not have been identified as such. This tool is a catalyst for other GSI planning efforts.

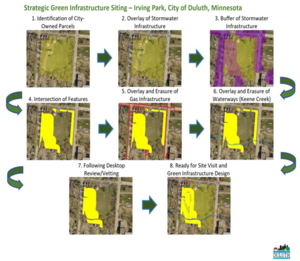

Overview of Duluth’s GSI Siting Tool

The City of Duluth developed a tool that identifies potential suitable locations for the implementation of GSI projects. This Geographic Information System (GIS)-based tool first identifies parcels that are city-owned, tax forfeited, or unbuilt road rights-of-way, then retains the portions of those parcels that are located within 75 feet of existing stormwater (e.g., storm sewers, catch basins, manholes, etc.), and finally removes areas with infrastructure conflicts (e.g., flowing streams, natural gas lines, etc.). After the GIS analysis, the locations that are identified by the tool undergo a desktop review. The review includes a manual assessment of other environmental, economic, or social information such as size of the selected site, social and environmental equity metrics (including MPCA’s environmental justice dataset), local slopes and topography, depth to infrastructure, potential impact on trout streams, known water impairments, etc. The GIS analysis and desktop review ultimately produces a shortlist of potentially suitable locations for GSI implementation, as illustrated in the adjacent figure. Sites that pass the desktop review process are then further inspected during a site visit.

While this tool was created specifically for Duluth, the approach and tool are replicable and applicable to other communities wishing to identify suitable GSI implementation locations. For reference, the City of Duluth spent approximately two to three weeks gathering the necessary GIS data, establishing the GIS methodology (including the queries used by the tool), and applying the tool. The desktop review process took approximately three to five additional weeks. This timeline can vary based on the availability and number of GIS data sets used in the analysis, the number of locations identified within GIS, and the parameters of interest considered in the desktop review.

How the GSI Siting Tool Informs Duluth’s GSI Planning Efforts

Using the GSI siting tool, the City has identified 203 feasible project areas across Duluth. This number fluctuates as stormwater infrastructure is updated or as understanding of the site-specific conditions develops. The City included these projects in their watershed management plans to identify the potential pollutant load reduction that could be achieved by these projects. Because the watershed management plans include a clear understanding of the watershed issues as well as an inventory of suitable GSI location, the City can use these in grant applications to obtain funding for GSI implementation. Because of the GSI siting tool, the City has been able to more competitively pursue Infrastructure and Investment Jobs Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law appropriations.

In addition to its primary use by the City for GSI siting on a large scale, the GSI siting tool also serves as a planning resource for collaboration and partnership with the City’s roads and other infrastructure projects. For example, city engineers planning a road design project can consult the GSI siting tool to identify if and where GSI can be incorporated into the project. This is particularly beneficial for smaller GSI projects that may not have been considered for construction as stand-alone projects but that make sense to include as part of a larger road reconstruction project.

References and Contact Information

- City of Duluth Sustainability page

- Climate Change and Green Infrastructure in Duluth, Minnesota

- A similar tool was developed by Murray County to identify suitable locations for solar development sites that would also contribute co-benefits such as agricultural preservation.

- For more information on the City of Duluth’s GSI siting tool, contact Ryan Granlund, Utility Programs Coordinator at the City of Duluth via phone at 218-730-4088 or via email at rgranlund@duluthmn.gov.

Rochester GSI Planning Case Study: 1st Avenue and 3rd Street Pocket Park, Rochester, MN

Brief overview of project In 2019, the City of Rochester (the “City”) completed construction on a pocket park in downtown Rochester that includes green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) such as rain gardens (bioretention) and permeable pavers. These GSI practices capture and treat runoff from a nearby parking ramp and street corridor, and reduce the pollutant load contribution to the South Fork Zumbro River, which is impaired for bacteria and turbidity. This project, funded by an EPA 319 Grant, emphasizes environmental education with an informational placard and an interactive push-button water pump that allows visitors to “play” with the GSI by bubbling water through the infiltration basin. The park also boasts public art – a limestone bubbling fountain – from Rochester-native artist Jenna Didier and benches for visitors to enjoy the green space. This park and its many social, economic, environmental, and aesthetic co-benefits paved the way for future GSI projects in the City.

Planning Process Highlights The City’s Public Works Department led the planning for the 1st avenue and 3rd street pocket park, starting circa 2015 with the development of Geographic Information System (GIS) tools to help site GSI in Rochester’s challenging environment that includes ultra-urban neighborhoods and an underlying Karst geology. Around this time, the US EPA also announced their 319 Grant Solicitations to fund projects that will reduce nonpoint source (NPS) pollution. The City used the GIS tools to identify potential locations for GSI that could be funded under the 319 Grant Program. Initially the City sought to partner with private developers on a new development project. Interest by private developers was limited however, because some of the grant requirements – such as including an educational component – went above and beyond what the developers were willing to invest at the time. The City subsequently pivoted to identify public facilities that could be retrofitted to include GSI. In 2018, the City performed a feasibility analysis to create a pocket park with GSI to capture and treat the runoff from a parking ramp and adjacent roadway. With the entire project footprint on public right-of-way, there was no need to include private partners. The public works department largely led this effort on its own with some input and collaboration from the City’s parks department. The public works Department also leads the maintenance of the GSI system, primarily due to the specialty maintenance required by the water pumps in the park.

To qualify for the 319 grant, the City was required to develop a Nine Element Watershed Based Plan (the “Nine Element Plan”), which is a detailed plan of how the proposed GSI will address (reduce) nonpoint source pollution. Quantifying the expected load reductions from the GSI was important to the Nine Element Plan as well as the City since these potential reductions have a direct beneficial impact to the South Fork Zumbro River, which is located downstream of the project and is impaired for turbidity and bacteria. In addition to estimating load reductions, the Nine Element Plan also requires an educational component. To address this requirement, the City designed the pocket park as an inviting place for public enjoyment, using benches, an informational placard, and an interactive water feature to draw in the public and provide educational information on stormwater. The interactive water feature is a central piece of the pocket park and includes a push-button water pump that bubbles water through the infiltration basin. While not required by the grant, the City also included public art as part of the pocket park – a limestone fountain that serves as a statement piece to highlight the connection between the local limestone geology and the waterways that flow through the City of Rochester.

There were no major roadblocks in the planning and development of the park. The City faced some public concern about the removal and conversion of 6 parking stalls to rain gardens. Neighboring businesses initially resisted the conversion of these parking stalls, concerned that removal of the stalls would negatively impact their business. The city actively engaged in discussions and outreach with the local businesses, making the case that the adjacent parking ramp provided enough parking stalls for customers and that the social, environmental, and aesthetic co-benefits of the project outweighed the loss in street parking. After these discussions, the neighboring businesses saw the value in having a pocket park in front of their businesses.

Funding the project was a big part of the planning process and presented some challenges. The 319 grant funding allowed the City to pursue this project, but the projected construction costs exceeded the grant funds. The Public Works Department had to go to the City Council to make the case for the project and request more money to complete the project. The Public Works Department highlighted the project’s many co-benefits, including the public space amenity and art installation by a local artist to obtain the additional funds from City Council.

Overall, the project timeline spanned approximately 5 years, starting with preliminary planning and tool development in 2015, grant application and feasibility analysis in 2016-2017, design in 2018, and construction starting in 2018 and finishing in 2019.

This project, along with recent stormwater ordinance changes driven by MS4 (Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System) permit requirements, has paved the way for future implementation of GSI. The new ordinance serves as a catalyst for GSI implementation while the pocket park serves as a GSI demonstration site to show GSI can be done in the City of Rochester.

Additional Information:

- Location: 1st Avenue and 3rd Street, Rochester, MN

- Owner & Designer : The City of Rochester

- Year of completion: 2019

- Design features

- Rain gardens

- Bioretention

- Permeable pavement

- Water reuse

- Pollutant Removal: Turbidity reduction

- Is the Site Publicly Accessible: Yes

- Notable Challenges

- Public buy-in

- Funding

- Co-Benefits

- Added greenspace

- Educational component

- Elevated aesthetics

This page was last edited on 3 January 2023, at 16:42.