Types of tree BMPs Revision as of 19:29, 22 October 2014 by Mtrojan (talk | contribs) (→Design considerations for trees growing in structural soil)

Many different types of tree BMP’s exist. The most prevalent types are described below.

Contents

- 1 Tree preservation

- 2 Incorporating trees into traditional bioretention practices

- 3 Techniques for providing uncompacted soil volume for tree growth and stormwater management under paved surfaces

- 4 References

- 5 Related pages

Tree preservation

Where existing trees exist, tree preservation is highly recommended, as existing trees are typically bigger than newly planted trees and bigger trees provide significantly more benefits than smaller trees.

Incorporating trees into traditional bioretention practices

Incorporating trees into traditional bioretention practices is Highly Recommended.

Accordingly, North Carolina’s bioretention standards recommend incorporating trees in all bioretention practices except for grassed cells: “A minimum of one (1) tree, three (3) shrubs, and three (3) herbaceous species should be incorporated in the bioretention planting plan unless it is a grassed cell. A diverse plant community is necessary to avoid susceptibility to insects and disease.”

Techniques for providing uncompacted soil volume for tree growth and stormwater management under paved surfaces

Where there is not enough open space for traditional bioretention, several techniques exist to protect soil volume under pavement from traffic compaction so that this soil can be used both for bioretention and tree root growth. Examples of these techniques are discussed below.

Structural cells (suspended pavement)

In areas that do not have enough open space to grow large trees, techniques like structural cells (suspended pavement) can be used to extend tree rooting volume under HS-20 load bearing surfaces and create favorable conditions to grow large trees in urban areas. This rooting volume can also be used for bioretention. While suspended pavement has been built in several different ways, all suspended pavement is held slightly above the soil by a structure that “suspends” the pavement above the soil so that the soil is protected from the weight of the pavement and the compaction generated from its traffic.

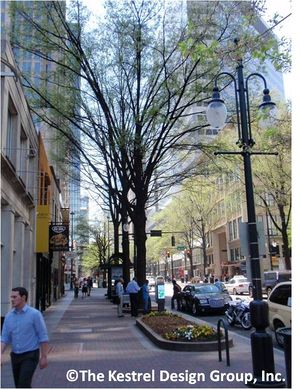

One of the earliest examples of trees grown in suspended pavement is in Charlotte, North Carolina, where a reinforced concrete sidewalk was installed over the top of poured in place concrete columns. While this is an effective way to grow large trees, it is labor intensive and requires intensive surveying to ensure that column heights are precise.

A more recently developed, and less labor intensive, technique to build suspended pavement is through the use of soil cells. An example is Silva Cells, modular proprietary pre-engineered structural cells manufactured by Deeproot Green Infrastructure. The modular design allows flexibility to size the rooting/bioretention volume as needed for each site. Underground utilities can be accommodated within Silva Cells systems. The Silva Cell system consists of silva cell frames that are 48 inches (1200 millimeters) long by 24 inches (600 millimeters) wide by 16 inches (400 millimeters) high. Frames can be stacked up to three high, and a deck is installed above the top frame. An air space between the top of the soil and the deck prevents tree roots in the upper soil layers from lifting the overlying pavement.

Because this soil in the Silva Cells is protected from compaction from loads on pavement above the cells, a wide range of soils can be used in the Silva Cells, so soil can be tailored to desired functions (e.g. tree growth and stormwater management). The Silva Cell system can support vehicle loading up to AASHTO H-20 rating of 32,000 pounds (14,500 kilogram) per axle. According to Deeproot’s website “This rating refers to the ability of a roadway to safely accommodate 3 and 4 axle vehicles, such as a large semi-truck and trailer.” The cells are made of “an ultra high-strength compound of glass and polypropylene, with galvanized steel tubes to add support and prevent plastic creep.”

Another example of a soil cell is StrataCell, which is supplied by Greenleaf. StrataCell’s matrix units lock together and form a monolithic framework with high modular strength. The open structure not only provides a growth zone for roots, but also permits conduits, service pipes and aeration mechanisms to be incorporated.

Despite their ability to support healthy tree growth, there may be limitations to the use of soil cells.

- Soil cell technologies cannot be prescribed, or detailed in manuals because they are proprietary products.

- Soil cell technology takes planning and coordination to integrate with complex utility systems.

- As proprietary products, their cost may be a barrier.

Rock based structural soil

Rock based structural soils are engineered to be able to be compacted to 95 percent Proctor density without impeding root growth. Rock based structural soils are typically gap graded engineered soils with the following components.

- Stones to provide load bearing capacity and protect soil in its void spaces from compaction. Desired characteristics for the stone base used in rock based structural soils include the following.

- The stones should be uniformly graded and crushed or angular for maximum porosity, compaction, and structural interface (Bassuk et al,, 2005).

- Mean pore size should be large enough to accommodate root growth (Lindsey, 1994).

- Significant crushing of stone should not occur during compaction (Lindsey 1994).

- Soil in rock void spaces for tree root growth. Soil needs to have adequate nutrient and water holding capacity to provide for the tree’s needs.

- Tackifier to keep the soil uniformly distributed in the rock void spaces (tackifier is only found in some kinds of rock based structural soil). Two (2) inch stones would be able to support most tree roots. The tackifier, if used, should be non-toxic and non-phototoxic.

Types of structural soils

Several types of rock based structural soils have been developed, including, for example:

- Cornell University (CU) structural soil: 80 percent stone with size ranging from 0.75 to 1.5 inches and 20 percent loam to clay loam soil with minimum 20 percent organic matter, by dry weight, and hydrogel to uniformly mix the stone and soil (CU, 2005). Patented formula available only from licensed producers to ensure quality control.

- University of California (UC) Davis structural soil: 75 percent lava rock (0.75 inches) and 25 percent loam soil (by volume) (Xiao and McPherson, 2008).

- Stalite structural soil: 80% Stalite, a porous expanded slate rock (0.75 inches), and 20 percent sandy clay loam soil (by volume)(Xiao and McPherson, 2008).

- Swedish structural soil (see [1])

Design considerations for trees growing in structural soil

Soil pH

Care must be taken to select species tolerant of structural soil pH. For example, if limestone-based structural soil is used, trees tolerant of alkaline pH must be selected, as limestone can raise the pH of soil to 8.0 or higher (Bassuk, 2010 soil debate).

Drainage Rate

Because rock based structural soils drain quickly ( greater than 24 inches per hour), designers should select tree species tolerant of extremely well drained soils (Bassuk 2010).

Volume of rock based structural soil needed for healthy tree growth

Because only 20 percent of the volume of a rock based structural soil is actually soil, a greater total volume of rock based structural soil is needed compared to growing the same size tree in a sandy loam soil. A pot study by Loh et al., (2003) found that 5 parts of structural soil were needed to provide the soil value of 1 part of loam soil (Loh et al, 2003). Similarly, an on-going study at Bartlett Tree labs is finding that over the past 9 years, trees growing in loam soil in suspended pavement have been consistently outgrowing trees growing in equal volumes of rock based structural soils, stalite soil, and compacted soil. See Task 4.1.C “Research Comparing Value of Rock Based Structural Soil to Traditional Tree Soils” for more information on thesestudies. Based on the above studies, Urban (2008) recommends:

- “Given the extreme inefficiency of the ratio of excavated volume to soil usable by the tree, strips of structural soil less than 20 feet wide might be better constructed as soil trenches or structural cells, where more soil can be included for less cost. A 5-foot wide soil trench set of structural cells…will provide more soil usable by the tree than a 20 foot wide trench of soil/aggregate structural soil.

- Soil/aggregate structural soils may have applications as a transition to other options, and to add soil in places where other options may not be practical. These might include tight, contorted spaces and fills around utility lines and against foundations where full compaction is required (p. 306)”

More information about rock based structural soils is available online,for example, at Cornell University’s website and a joint website by Cornell University’s, Virginia Tech, Rutgers University, and University of California Davis

Sand based structural soil

Sand based structural soils were first developed in Amsterdam when some trees were in poor condition because of an “unfavorable rooting environment” (Couenberg 1993). Because the natural soils in Amsterdam (bog-peat) were non-load bearing, the top 2 meters of soil had been replaced with a medium coarse sand which had insufficient nutritional value. Amsterdam soils were developed in an effort to grow better trees but still provide adequate bearing capacity for pavement bearing light loads, such as sidewalks. The Dutch studied various mixes for tree growth, soil settlement, and several other parameters. The resulting Amsterdam Tree Soil contains medium coarse sand with 4 to 5 percent organic matter and 2 to 4 percent clay by weight and also meets other criteria, including the following.

- The medium coarse sand must meet specific gradation requirements.

- The soil mix must be free of salt.

- The mix must contain less than 2 percent particles below 2 micrometers.

- the amount of particles below 2 micrometers must be considerably less than the amount of organic materials (Couenberg 1993).

All medium coarse sand (the layer above the Amsterdam Tree Soil) is compacted to 95 to 100 percent Proctor density. Amsterdam Tree Soil is not compacted to 100 percent density, but “is compacted until the soil has a penetration resistance between 1.5 and 2 MegaPascal (187 to 250 pounds per square inch)...Comparison of soil density values after filling with soil density at 100 percent Proctor Density has shown that soil density of Amsterdam Tree Soil after filling amounts to 70 to 80 percent Proctor Density” (Couenberg 1993). Amsterdam Tree Soil was found to settle 19 millimeters [0.75 inches] in 3 years compared to the surrounding pavement, which was acceptable according to Dutch standards (Couenberg 1993). This settling may not be acceptable to many communities in the United States due to litigation risk associated with trip and fall hazards.

The standard design in Amsterdam includes the following from bottom to top.

- ground water table 1 to 1.2 meters below ground level;

- saturation zone 10-20 cmentimeters;

- layer of compacted, non-saturated sand;

- Amsterdam Tree Soil compacted in 2 layers of 40 to 50 centimeters;

- compacted layer of 10 cm medium coarse sand for paving; and

- pavement, typically concrete pavers 30 by 30 by 5 centimeters (Couenberg 1993)

Soil boxes

Soil boxes are concrete boxes designed for bioretention. They are typically proprietary products, such as, for example, the boxes made by Filterra and Contech.

Rooting volume capacity of these boxes is typically limited to large shrubs. Soil volumes provided by these boxes are typically not sufficient to grow healthy large trees. A standard 6 foot by 6 foot Filterra box, for example, provides 72 cubic feet of soil, assuming a 2 foot depth of soil. Given that the recommended soil volume for trees is 2 cubic feet of soil per 1 square foot of tree canopy, this is only enough to support a tree with a 5 foot radius canopy.

References

- Bassuk, Nina. 2010. Using CU-Structural Soil to Grow Trees Surrounded by Pavement. In The Great Soil Debate Part II: Structural soils under pavement. ASLA Annual Meeting Handout.

- Bassuk, Nina, Jason Grabosky, and Peter Trowbridge. 2005. Using CU-Structural Soil™ in the Urban Environment.

- Cornell university. 2005. Using CU-Structural Soil™ in the Urban Environment.

- Couenberg Els. A.M. 1993. Amsterdam Tree Soil. In: The Landscape Below Ground. Proceedings of an international workshop on tree root development in urban soils.

- Grabosky, Jason, Edward Haffner, and Nina Bassuk. 2009. Plant Available Moisture in Stone-soil Media for Use Under Pavement While Allowing Urban Tree Root Growth. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry 35(5): 271-278.

- Lenth, John and Rebecca Dugopolski (Herrera Environmental Consultants), Marcus Quigley, Aaron Poresky, and Marc Leisenring (Geosyntec Consultants). 2010. Filterra® Bioretention Systems: Technical Basis for High Flow Rate Treatment and Evaluation of Stormwater Quality Performance. Prepared for Americast, Inc.

- Lindsey, Patricia, Ed. 1994. The Design of Structural Soil Mixes for Trees in Urban Areas – Part II. Growing Points 1(2). University of California.

- Xiao, Qingfu, and E. Greg McPherson. 2008. Urban Runoff Pollutants Removal Of Three Engineered Soils. USDA Center for Urban Forest Research and UC Davis Land, Air and Water Resources.

Related pages

- Overview for trees

- Types of tree BMPs

- Plant lists for trees

- Street sweeping for trees

- References for trees

- Supporting material for trees

The following pages address incorporation of trees into stormwater management under paved surfaces

- Design guidelines for tree quality and planting - tree trenches and tree boxes

- Design guidelines for soil characteristics - tree trenches and tree boxes

- Construction guidelines for tree trenches and tree boxes

- Protection of existing trees on construction sites

- Operation and maintenance of tree trenches and tree boxes

- Assessing the performance of tree trenches and tree boxes

- Calculating credits for tree trenches and tree boxes

- Case studies for tree trenches and tree boxes

- Soil amendments to enhance phosphorus sorption

- Fact sheet for tree trenches and tree boxes

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using trees as a BMP in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using trees with an underdrain as a BMP in the MIDS calculator