TCMA Chloride Management Plan - TCMA Chloride Conditions

Contents

TCMA Chloride Conditions

Chloride data across the TCMA was compiled and assessed to support the development of the CMP. As part of the TCMA Chloride Project, the MPCA worked with local partners to develop and implement a chloride monitoring program. The objective of the monitoring program was to better inform an understanding of chloride conditions across the TCMA, including seasonality, trends over time, and the potential for high chloride concentrations in the deepest part of lakes. Seventy-four lakes, 27 streams, and eight storm sewers were monitored as part of this effort from 2010-2013. The Chloride Monitoring Guidance for Lakes and Chloride Monitoring Guidance for Streams and Stormsewers were developed by the MPCA and local experts from the TCMA Chloride MSG and can be found on the MPCA’s TCMA Chloride Project website. The monitoring guidance provides recommendations on sample collection, times of the year to sample, as well as guidance for monitoring high risk waters. In addition to data collected in 2010-2013 following the TCMA Chloride Project monitoring program, chloride data from a host of other sources and timeframes were compiled. The data were collected by several local organizations including the MPCA, the United States Geological Survey (USGS), Capitol Region Watershed District (CRWD), Metropolitan Council Environmental Services (MCES), Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board (MPRB), Minnehaha Creek Watershed District (MCWD), Mississippi Watershed Management Organization (MWMO), Ramsey County Environmental Services, Ramsey-Washington Metro Watershed District (RWMWD), Rice Creek Watershed District, Scott County Watershed Management Organization, and Three Rivers Park District. A large portion of the data were compiled and submitted to the State of Minnesota’s Environmental Quality Information System database (EQuIS). All data collected by Metropolitan Council are available on their Environmental Information Management System (EIMS) database, and data collected by USGS are available on their water-quality data for the Nation database: waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/qw.

The impacts of climate change create uncertainty related to winter salt application and chloride levels in TCMA waters in the future. Predictions provided by the United States Global Change Research Program for the TCMA area include warmer winter temperatures by 5 - 6 degrees Fahrenheit, longer freeze-free seasons increasing by 20-30 days, greater winter precipitation, and the likelihood of more frequent extreme events (Kunkel et al. 2013). On the one hand, these predictions of climate change may result in reduced salt use. On the other hand, more frequent snow events, more extreme events, and potentially more frequent ice storms may result in greater needs for deicing roads. Continued monitoring of climate change and chloride concentrations in the TCMA waters, tracking of salt use on all paved surfaces, and an adaptive process will be needed to restore and protect the TCMA waters from chloride impairments with the prospects of a changing climate.

The remainder of this section will present an overview of the assessments conducted based on the available data, including determinations of impairment, time and spatial trends in chloride concentrations, the TMDLs developed for impaired waters, and waters showing a high-risk for future impairment.

Condition Status

This section describes the current status of water resources within the TCMA with respect to applicable chloride criteria. The status of surface waters including lakes, wetlands and streams is presented first. The status of groundwater resources is presented second.

Surface Water

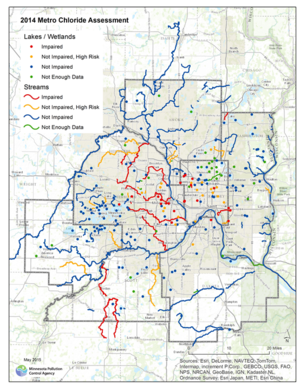

The MPCA’s approach to determining whether or not a stream, lake, or wetland is impaired by chloride relies on an assessment of available data. The MPCA conducted an assessment for chloride in the TCMA waterbodies in 2013. Two or more exceedances of the chronic criterion of 230 mg/L within a three-year period are considered an impairment. One exceedance of the acute criterion of 860 mg/L is considered an impairment. The 2013 TCMA chloride assessment resulted in 29 new chloride impairments (6 streams, 19 lakes, and 4 wetlands) added to the 2014 draft impaired waters list, resulting in a total of 39 chloride impairments in the TCMA. Shingle Creek and Nine Mile Creek were previously listed as impaired with completed chloride TMDLs. Approximately 11% of the 340 waterbodies assessed were determined to be impaired. An additional 38 (11%) were classified as high risk and 11% did not have enough data. High risk was defined as a waterbody having one sample in the last 10 years that was within 10% of the chronic criteria (207 mg/L). An interactive map showing assessed, impaired, not impaired, and high risk waters is on the MPCA Chloride Project website (MPCA Chloride Project Website Map of Assessments and Impairments). The assessed lakes, wetlands, and streams are shown on Figure 1. The highest density of impairments is in the heavily urbanized area in Hennepin and Ramsey Counties, though three streams in the outlying suburban areas are also impaired by chloride. The chloride causing impairments in the streams in the outlying areas of the metro is largely effluent from the WWTPs, rather than deicing salt.

It is important to keep in mind that of the over 1,000 lakes, wetlands and streams in the TCMA, less than one-third had chloride data to make an assessment of impairment/attainment of water quality criteria. Also, of those waters with adequate data to make an assessment, only 30% were part of the TCMA Chloride Project monitoring program, which was developed to collect samples at critical times of the year and critical locations. As a result, data used to evaluate water quality conditions in waters not part of the TCMA Chloride Project monitoring program, may not have been representative of critical conditions. Critical times of the year for collecting chloride samples are typically during the winter snowmelt runoff (February through March) and during low flow periods, and critical areas for collecting chloride samples in a lake are near the bottom.

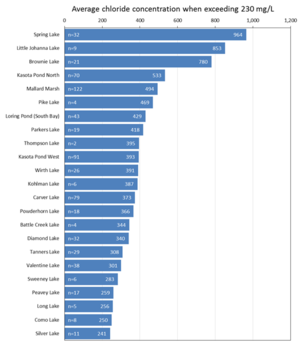

The impaired lakes, wetlands, and streams were compared by the concentrations of chloride ranked from highest to lowest concentrations. These rankings are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. These figures are not a direct reflection of the 303(d) listing assessment; they are intended to make a relative comparison of the extent of impairment across impaired waters. The values presented in these figures were calculated by identifying the maximum chloride concentration measured in a waterbody on individual sampling days, then averaging all individual sampling day maximums that exceeded the standard of 230 mg/L from 2003-2013. These figures indicate the variability in one waterbody or watershed to the next by the severity of the impairment. These rankings can be used by chloride users to prioritize management activities by area. Since only a portion of the TCMA waters have chloride monitoring data, the rankings can also be used to determine specific areas that are close to impaired and high-risk watersheds for further monitoring and higher levels of management.

Groundwater

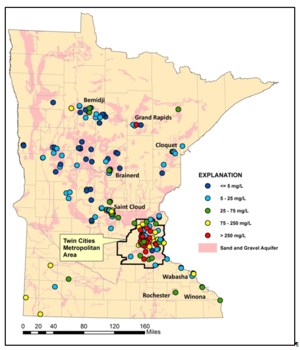

Chloride concentrations in shallow groundwater are increasing, likely as a result of the application of deicing salt. This correlation is observed in a recent study by the MPCA, The Condition of Minnesota’s Groundwater, 2007-2011, which found that chloride concentrations were higher in wells sampled in urban areas, where salt is more commonly applied in winter months, compared to wells sampled in areas that were undeveloped (Table 2).

Average chloride concentrations in groundwater based on land use

Link to this table

| Land Use | Chloride (mg/L) |

|---|---|

| Residential | 45 mg/L |

| Commercial/Industrial | 60 mg/L |

| Undeveloped | 15 mg/L |

The median chloride concentration in sand and gravel aquifers in the TCMA was 86 mg/L, compared to a median concentration of 17 mg/L in sand and gravel aquifers outside the TCMA. Twenty-seven percent of sand and gravel monitoring wells in the TCMA had chloride concentrations greater than 250 mg/L, the secondary maximum contaminant level set by the EPA (Figure 4). Very few monitoring wells outside the TCMA (about 1%) had chloride concentrations exceeding 250 mg/L.

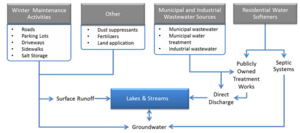

Chloride Sources

Chloride enters the TCMA lakes, streams, wetlands, and groundwater from a variety of sources. The relative significance of each source of chloride is dependent on the watershed. For highly developed urban areas, winter maintenance activities are typically the primary source. In less developed areas where point source discharges exist, the municipal wastewater treatment facilities may be the primary source of chloride, which in most cases is due to water softening. A conceptual model diagram of the primary anthropogenic sources is shown in Figure 5. A chloride budget for the TCMA estimated that only 22%-30% of the chloride applied in the TCMA was exported out of the TCMA via streamflow in the Mississippi, Minnesota, and St. Croix Rivers (Stefan et al. 2008). Therefore, 70%-78% of the applied chloride remains in TCMA lakes, wetlands, and groundwater and it may also be stored in soil-water where infiltration is slow. Since chloride is an element and does not breakdown over time, the high percentage retained in the TCMA suggests that chloride will continue to accumulate and eventually make its way to the deep aquifers. This implies that, on average, chloride concentrations in the TCMA waterbodies are increasing with time. If the chloride loading remains steady, the concentrations will level out when equilibrium develops between loadings and transport out of the TCMA. By the same token, if loadings are reduced sufficiently and persistently, the chloride concentrations in the TCMA waterbodies will begin to decrease and will continue to decrease until a new equilibrium is reached. Each of these sources is briefly described below.

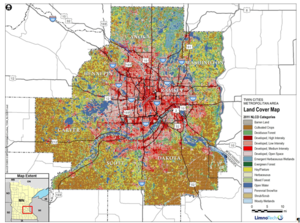

As shown in Figure 6, land use in the TCMA is largely urban in the core of Minneapolis and St. Paul with a transition to rural and agricultural moving outward through the suburbs. The primary source of chloride may shift locally depending on land use. Section 2.3 discusses the correlation of road density and chloride concentrations in surface waters.

Winter Maintenance Activities

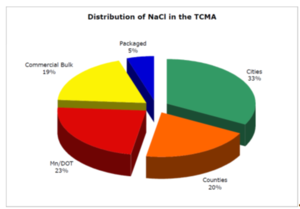

Winter maintenance activities include snow and ice removal. Application of deicing and anti-icing chemicals, primarily salt, is common. Salt is applied to a variety of surfaces including roads, parking lots, driveways, and sidewalks. Runoff from salt storage facilities is another potential source of salt. The St. Anthony Falls Laboratory at the UMN developed an inventory of salt uses in the TCMA for a Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) Local Roads Research Board study (Sander et al. 2007). The inventory estimated the total amount of salt used for winter maintenance activities in the TCMA, based on purchasing records, to be 349,000 tons per year. Estimates of use by various entities are shown in Figure 7.

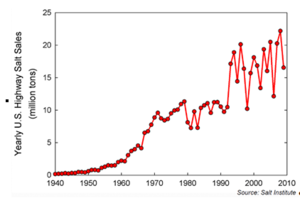

Salt sales data in the United States shows a dramatic increase in the amount of salt being purchased. Figure 8 below from the Salt Institute illustrates this increasing trend. Along with the increased use of salt, increasing levels of chloride in lakes, wetlands, and streams should be expected.

Roads

The TCMA is estimated to have over 26,000 lane miles of roadways (Sander et al. 2007). Application rates range from 3 to 35 tons of road salt, per lane mile, per year, based on the salt purchasing records and the number or lane miles of MnDot, counties, and cities in the TCMA (Wenck 2009)

A survey of municipal winter maintenance professionals in the TCMA, done by LimnoTech in 2013, found that typical application rates range from 100 - 600 pounds of salt applied per lane mile per event, which is consistent with previous evaluations of road salt application rates. However, rates can be much higher on hills, near intersections, and other ice problem areas. Higher speed roadways will typically have higher road salt application rates. Some events may require multiple passes of salt application and increase the application rate per event.

=Commercial Parking Lots, Driveways, and Sidewalks

Commercial sources of deicing salt can vary greatly between different watersheds and includes salt applied to parking lots, driveways, and sidewalks on commercial property. The land owner or tenant may conduct winter maintenance activities, or winter maintenance may be contracted with private winter maintenance providers. Commercial sources are likely responsible for 10% and 20% of the total salt applied to paved surfaces in the TCMA (Wenck 2009). The MPCA and Fortin Consulting conducted research to validate and refine assumptions regarding commercial and private salt application rates specific to Minnesota (Fortin 2012a). There is a range of reported application rates, which is to be expected, because rates should vary based on temperature, type of snow event, surface to where material is applied, number of passes over an area during an event, and type of material used. Application rates of salt on parking lots are estimated to range from 0.1 to 1 ton per acre per event, and typically 6.4 tons per acre per year. For sidewalks, the application rate is estimated to range from 8 to 25 pounds per 1,000 square feet per event (0.2 to 0.5 tons per acre per event). More area specific residential and commercial estimates of chloride usage can be determined on a watershed basis by digitizing all of the residential and commercial impervious surfaces and multiplying by the estimated application rates.

Review of available information and additional research included application rates from across the United States’ and Canada’s snowbelt, with an emphasis on Minnesota specific data. It was determined that an average rate of 6.4 tons per acre per event is the appropriate application rate to expect on parking lots. As a percent of the total deicing salt usage, it is estimated that anywhere between 5% and 45% is used for commercial applications (parking lots, sidewalks, residential, private roads). The amount of chloride from commercial sources is variable, and is dependent on the characteristics of the watershed, including the amount of impervious area. Additional estimates of commercial salt use are presented below.

- The Nine Mile Creek Chloride TMDL report, used data on salt purchases from Sander et al. (2007) and Novotny et al. (2008), but weighted the data based on land use. It was determined that the relative contribution for commercial and packaged deicer in the Nine Nile Creek watershed was 38% of the total amount of road salt that is applied (Barr Engineering 2010).

- In the Shingle Creek TMDL, it was estimated that 7.5% of salt application was by commercial/private applicators. This figure was based on the estimates used in Canada. “Cheminfo (1999) estimated that commercial and industrial consumers represented approximately 5 to 10% of the deicing salt market. In quantifying total deicing salt application in Canada, Environment Canada used the midpoint of these data (7.5%) to represent commercial and industrial salt application (Environment Canada 1999).” (Wenck 2006).

- Sander et al. (2007) estimated that the bulk deicing salt applied by commercial snow and ice control companies accounted for 19% of the total salt used in the TCMA, while packaged deicer for home and commercial use was estimated to account for 5% of the total in the TCMA.

- Novotny et al. (2008) used market share amounts from the USGS annual mineral reports and the market share report published annually from the Salt Institute. TCMA amounts were estimated based on national amounts combined with the commercial bulk (19%) and packaged (5%) deicer estimates for a total of 24%.

- On a national basis, the Salt Institute estimated that 20% of bulk road salt purchases were by non-governmental entities.

- The USGS estimated 13% of ice control salt is for commercial use.

- A chloride TMDL study in New Hampshire reported a chloride application rate of 5.7 to 6.4 tons per acre per year for parking lots and drives (Sassan and Kahl 2007). Parking lots were 47% of paved surfaces in the watershed and accounted for 36% of the chloride load. The study also estimated that 45% of salt was applied by private applicators.

Private Parking Lots, Driveways, and Sidewalks (residential)

Residential winter maintenance salt use has been estimated from purchasing records. Packaged deicer for home and commercial use is estimated to account for 5% of the total in the TCMA (Sander et al. 2007). See Figure 7.

A Sidewalk Salt Survey was conducted to qualitatively assess the use of sidewalk salt by the general public in the TCMA. The survey was disseminated by local partners including RWMWD, MCWD, and MnDOT. The survey was administered through an on-line Survey Monkey link on the MCWD website (www.minnehahacreek.org) from November 2011 through March 2012. The survey was completed by 606 people online and 148 completed a paper survey. Approximately 47% of the respondents lived in St. Paul or Minneapolis, and other respondents lived in surrounding cities including Woodbury, Richfield, Plymouth, and Maplewood. Although the survey sampled 754 residents, the results represent a small percentage of the TCMA population and are non-random/voluntary; therefore, the survey is not representative of all residents in the TCMA. However, the data provide valuable information on the use of sidewalk salt by TCMA residents.

The majority of residents that responded to the survey used sidewalk salt (57%), particularly on sidewalks and steps. Most people selected products based on performance in colder temperatures and environmental safety. The majority of respondents did not know how much sidewalk salt to use (59%), and if they did know, they determined how much to use based on the instructions on the packaging or used as little as possible. For complete results of the survey see Appendix C.

Municipal and Industrial Treatment Facilities

Municipal wastewater, backwash from municipal WWTPs, and industrial facilities with waste streams may contain chloride. The primary source of chloride in a municipal waste stream comes from water softeners. Many cities do not soften drinking water before it is distributed to residents. Many residents soften the water in their home with personal water softeners. The most common water softening