Credits for Better Site design Revision as of 19:04, 17 January 2013 by Mtrojan (talk | contribs) (→Site reforestation or prairie restoration credit)

The six better site design approaches that could be eligible for water quality volume reduction stormwater credits include:

- Natural Area Conservation

- Site Reforestation or Prairie Restoration

- Drainage to Stream or Shoreline Buffers

- Surface Impervious Cover Disconnection

- Rooftop Disconnection

- Use of Grass Channels

For consistency with other sections of this Manual, the formulas for computing water quality volumes and related credits are based on the requirements contained in the MPCA Construction General Permit (CGP). These formulas provide just one option for local authorities to consider. The approach used in these examples subtracts the credit volume from the water quality volume (Vwq); the volume of a permanent pool (Vpp) in a stormwater pond or wetland is not adjusted. Other options that could be considered include applying credits to Vpp, or proportional application of a credit to both Vpp and Vwq.

It is not the intention of this system of credits to eliminate the need for a water quality volume. It is possible that the area proposed for conservation exceeds the area proposed as impervious surface. In this circumstance, it is recommended that a minimum water quality volume equal to 0.2 watershed inches be maintained (see Unified sizing criteria).

Local authorities should keep in mind that the current MPCA CGP, which expires in 2008, does not incorporate a technique for application of these credits. This CGP does allow up to a maximum of 1% of a site, up to three acres to drain untreated to natural areas, in sites where any BMP is not feasible.

Although stormwater credits are not currently used under the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Construction General Permit (CGP), they can be applied at the local and watershed levels to supplement the CGP or be used for projects not covered under the CGP. Credits can also be used as part of the financial evaluation under a local stormwater utility program, similar to the Minneapolis approach. Further evaluation of the use of credits in the CGP process will occur as part of the permit update process over the next year.

Although not explicitly allowed under the current MPCA CGP, there are situations where a local authority could create a water quality credit system which does not conflict with the CGP. For example, a local authority that requires a water quality volume that is greater than the CGP water quality volume, could apply credits against the difference between the two volumes. Another situation appropriate for credits could be retrofit projects that do not create new impervious surfaces. These projects are not subject to permanent stormwater management requirements of the CGP. Local authorities interested in establishing a credit system prior to expiration of the CGP in 2008, are encouraged to contact the MPCA to explore if the local proposal is compatible with the CGP.

The last section presents tips on how to establish and administer a local stormwater credit system, with an emphasis on review and verification during concept design, final design and construction.

Contents

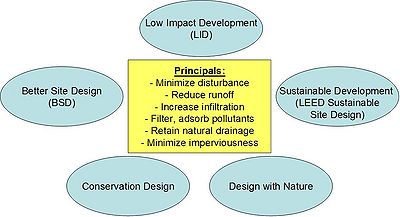

Better site design and stormwater credits

There are more than a dozen better site design techniques that can be applied at development sites. When applied early in the design process, these techniques can dramatically reduce stormwater runoff and pollutants generated from development sites (CWP, 1999). In recent years, several states have sought to encourage greater use of better site design techniques by allowing for computation of stormwater credits that reduce the required water quality volume that must be provided at a development site.

Agencies that utilize stormwater credits can sharply reduce water quality and stormwater management BMP size requirements and recommendations. This translates directly into cost savings for developers since the size and cost of stormwater conveyance and treatment systems needed for the site are reduced, and less land area is needed for BMPs. The use of credits by developers is strictly voluntary, although they do offer a meaningful incentive to reduce the cost of stormwater compliance.

Stormwater credits are tied directly to the water quality volume requirements (Vwq and Vpp). In addition, credits can be used to reduce the storage volumes needed to manage larger storm events, such as any locally-required channel protection and overbank floods (by increasing times of concentrations and reducing curve numbers in post-development hydrological modeling). Not all credits will be available for each site, and certain site-specific conditions should be met to receive each credit. These minimum conditions include site factors such as maximum flow length or contributing area that avoid situations that could lead to runoff concentration and erosion. Stormwater credits do not relieve designers from the normal standard of engineering practice of safe conveyance and drainage design. Multiple credits can be used at a development site, although two credits cannot be taken for the same physical area of the site.

Summary of stormwater credits function illustrating how to calculate water quality volume, channel protection and overbank storm volumes for different Better Site Design credits.

Link to this table.

| Stormwater credit | Adjusted water quality volume | Channel protection and overbank storms |

|---|---|---|

| Natural area conservation | Subtract CA from site IC when computing Vwq | Adjust CN for CA to woods in good condition |

| Site reforestation/prairie restoration | Subtract 1/2 RA from site IC when computing Vwq | Adjust CN for RA to woods or prairie in fair condition |

| Streams and shoreline buffers | Subtract ADB from site IC when computing Vwq | Adjust CN for ADB to woods in good condition |

| Surface impervious cover and disconnection | Subtract DIA from site IC when computing Vwq | Adjust CN for DIA to grass in good condition. Adjust Tc |

| Rooftop disconnection | Subtract DRA from site IC when computing Vwq | Adjust CN for DIA to grass in good condition. Adjust Tc |

| Grass channels | Subtract GA from site IC when computing Vwq | Adjust Tc |

Note: Unless otherwise noted, all units below are measured in acres

- CA = combined area of all natural areas conserved at site

- RA – Total area of site reforestation or prairie restoration

- ADB – Total area draining to buffer with appropriate flow path distance

- DIA – Total area of surface impervious cover that can be effectively disconnected

- DRA – Aggregate rooftop area that can be effectively disconnected

- GA - total non-roadway area draining to swale (rooftop, yard and driveway)

- CN – Runoff curve number for area (units: dimensionless) (see Ch.8 and App. B)

- Tc – Time of Concentration (units: time)

Vwq – Water quality volume, as defined by relevant MPCA sizing rule - IC - Impervious area of site (acres)

Stormwater credit categories

Six credit categories are addressed in this section.

- Natural Area Conservation Credit

- Site Reforestation or Prairie Restoration Credit

- Drainage to Stream, Wetland or Shoreline Buffer Credit

- Surface Impervious Cover Disconnection Credit

- Rooftop disconnection credit

- Grass channel credit

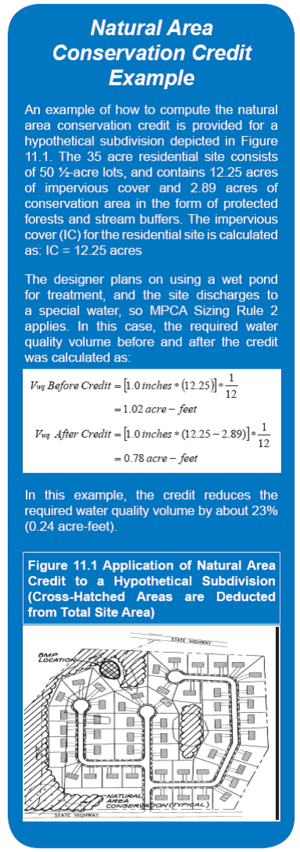

Natural area conservation credit

Natural area conservation protects natural resources and environmental features that help maintain the pre-development hydrology of a site by reducing runoff, promoting infiltration and preventing soil erosion. Natural areas should be eligible for stormwater credit if they remain undisturbed during construction and are protected by a permanent conservation easement prescribing allowable uses and activities on the parcel and preventing future development. Examples of conservation areas include any areas of undisturbed vegetation preserved at the development site, such as forests, prairies (native grasslands), floodplains and riparian areas, ridge tops and steep slopes, and stream, wetland and shoreline buffers. Floodplain credits should not be issued to areas that cannot be developed due to existing floodplain ordinance restrictions.

The undisturbed soils and native vegetation of conservation areas promote rainfall interception and storage, infiltration, runoff filtering and direct uptake of pollutants. Portions of the site devoted to natural area conservation are eligible for two credits, such as the addition of a buffer credit.

Water quality

The total combined area of all conservation areas can be subtracted from total site area when computing the water quality volume (Vwq) portion of the total storage volume. In the context of the four MPCA Vwq [[Unified sizing criteria|sizing rules, the credit is numerically expressed as:

Rule 1 (Stormwater Ponds and Constructed Wetlands) and Rule 3 (Non-Ponds):

Vwq=1815(IC−CA)

where:

- Vwq = required water quality volume in cubic feet;

- IC = new site impervious cover, in acres;

- CA = total natural area conserved at site, in acres; and

- 1815 = conversion factor (to cubic feet)

Rule 2 (Stormwater Ponds and Constructed Wetlands Draining to Special Waters) and Rule 4 (Non-Ponds Draining to Special Waters):

Vwq=3630(IC−CA)

where:

- Vwq = required water quality volume in cubic feet;

- IC = new site impervious cover, in acres;

- CA = total natural area conserved at site, in acres; and

- 3630 = conversion factor (to cubic feet)

Larger storm events

The post-development curve number (CN) used to compute the Vcp, Vp10, and Vp100 for all natural conservation areas can be assumed to be “woods or prairie in good condition” when calculating the total site CN.

Conditions for credit

- The minimum combined area of all natural areas conserved at the site must exceed one acre. Full ecological function for natural grassland (prairie) begins at 5 acres and for forested land starts at 20-40 acres. Credits could be increased beyond 1:1 for acreages that approach and exceed these values.

- No disturbance may occur in the conservation area during or after construction (i.e., no clearing or grading except for temporary disturbances associated with incidental utility construction or restoration operations, or removal of nuisance vegetation).

- The limits of disturbance around each conservation area should be clearly shown on all construction drawings.

- A long-term vegetation management plan must be prepared to maintain the conservation area in a natural vegetative condition. Managed turf is not considered an acceptable form of vegetation management, and only the passive recreational areas of dedicated parkland are eligible for the credit (e.g., ball fields and golf courses are not eligible).

- The conservation area must be protected by a perpetual easement that clearly specifies that no future development or disturbance can occur within the area.

- The credit cannot be granted for natural areas already protected by existing federal, state, or local law.

- Conservation areas should be preserved to maximize contiguous area and avoid habitat fragmentation.

- Credits should be considered for establishing native plant community corridors or naturally vegetated connections between sites.

Site reforestation or prairie restoration credit

[[File:Site reforestation credit example.png|thumb|300px|alt=schematic showing an example for calculating credits for site reforestation|Schematic showing an example for calculating credits for site reforestation. see NOTESCite error: Invalid <ref> tag;

invalid names, e.g. too many==

- Capiella, K, T. Schueler and T. Wright. 2005. Conserving and planting trees at development sites. USDA Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry. Center for Watershed Protection. Ellicott City, MD.

- Center for Watershed Protection (CWP). 1998. Better Site Design: a handbook for changing development rules in your community. US EPA. Center for Watershed Protection. Ellicott City, MD.

- Center for Watershed Protection (CWP). 1999. Nutrient loading from conventional and innovative site development. Chesapeake Research Consortium. Center for Watershed Protection. Ellicott City, MD.

- Chang, M., M. McBroom, R. Beasley. 2004. Roofing as a source of nonpoint water pollution. Journal of Environmental Management. 73: 307-315.

- Chollak, T and R. Rosenfield 1998. Guide for landscaping with compost amended soils. Department of Public Works. City of Redmond, WA.

- City of Portland. 2004. Portland’s Stormwater Management Manual. Bureau of Environmental Services. Portland Oregon.

- City of Seattle, 2003. How soil amendments and compost can aid in Salmon recovery.

- Horsely, S. 1996. Memorandum dated July 10, 1996. Methods for Calculating Pre and Post-development Recharge Rates. Prepared for State of Massachusetts Stormwater Technical Advisory Group.

- Metropolitan Council (MC). 2001. Minnesota urban small sites BMP Manual: Stormwater best management practices for cold climates. Metropolitan Council Environmental Services. St. Paul. MN.

- Minnehaha Creek Watershed District (MCWD), 2001. Benefits of Wetland Buffers: A Study of Functions, Values, and Size. Prepared for MCWD by EOR. Oakdale, MN. 41pp.

- Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, 2000. Conserving Wooded Areas in Developing Communities; Best Management Practices in Minnesota. www.dnr.state.mn.us/forestry/urban/bmps.html.

- Minnesota Forest Resources Council. 1999. Sustaining Minnesota Resources: Voluntary Site-Level forest Management Guidelines for Landowners, Loggers, and Resource Managers. (General Guidelines pp. 22-23). Minnesota Forest Resources Council, St. Paul, MN.

- Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA). 2002. Protecting Water Quality in Urban Areas. St Paul. MN.

- Pitt, R. 1989. Small Storm Hydrology: The integration of flow and water quality for management practices University of Alabama-Birmingham.

- State of Maryland. 2000. Maryland Stormwater Design Manual. Volume I and II. Maryland Department of Environment. Baltimore, MD.

- State of New York. 2003. Stormwater Management Design Manual. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY.

- State of Vermont, 2002. The Vermont Stormwater Management Manual-Final Draft. Vermont Agency of Natural Resources, Waterbury, VT.

- USDA. 1986. TR-55 Urban Hydrology for Small Watersheds.

- Winer, R. 2000. National Pollutant Removal Database for Stormwater Treatment Practices: 2nd Edition. Center for Watershed Protection. Ellicott City, MD.

Notes

- ↑ Several images in this section, including this image, were taken from the 2008 Stormwater Manual. Terms may differ somewhat from the text on this page. For example, equations have been rearranged so that a single numeric value is used for conversion to cubic feet. Also note that references to table or figure numbers are from the 2008 manual and have no relevance for this website.