MS4 fact sheet - Open Space Design

Open space design is a form of residential development that concentrates development in a compact area of the site to allow for greater conservation of natural areas. This form of development may also be called cluster design, conservation design, or low impact development (LID). Many of the typical management practices associated with open space design and LID include

- reducing impervious surfaces,

- using pervious pavements and green roofs,

- rainwater harvesting,

- urban forestry,

- use of vegetated swales and buffers, and

- establishing an infiltration standard.

This fact sheet presents guidance on the development of an ordinance to encourage the use of open space design and LID

Contents

Benefits and pollution reduction

Research has shown that open space designs can more effectively reduce a site’s overall impervious cover compared to conventional subdivisions, and command higher prices and more rapid sales because of the attraction of open space and preserved natural features (Zielinski, 2001). Other benefits include lower costs for grading, erosion control, stormwater and site infrastructure, as well as greater land conservation, without the loss of developable lots. Increased open space and less runoff directly translates into lower pollutant loads to downstream waters, protecting lakes, streams and wetlands. This is especially true when the preserved open space is tied into a well designed overall site runoff management plan. Open space design can revitalize city centers, increase the quality of life of its citizens and attract tax-paying businesses and residents to the area.

Program development and implementation

Open space design techniques

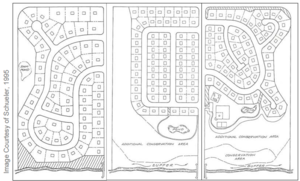

Open space design is a form of development that allows for greater conservation of natural areas. Approaches include relaxed minimum lot sizes, setbacks and frontage distances in order to maintain the same number of dwelling units at the site while creating more open space.

A mixed-use approach that integrates usable grassed park space with a trail system among restored native ecosystems and preserved drainageways and wetlands can be a very effective approach. Shared driveways and utilities is one example of impervious surface reduction that can facilitate the preservation of open space.

The residential development Fields of St. Croix, in Lake Elmo, MN, was completed in 2004 and is an example of open space design. The development includes 113 single family homes and 12 attached single family homes with lot sizes ranging from 0.35- to 1-acre. The 241-acre site leaves 144 acres (60 percent) as open space. The development maximized open space using cluster development techniques. Street widths are sized appropriate to their function ranging from 14-foot one-way lanes to 24-foot two-way lanes. More than 90 acres of farmland are preserved and functions as a community-supported agricultural farm with paying members. Additional open space consists of prairie and oak savanna and a pond and associated preserved shoreland. The site also uses a constructed wetland wastewater treatment system for the entire development.

For additional design techniques that identify ways to preserve more open space (e.g. smaller parking lots, slimmer sidewalks and streets), see the Reducing Impervious Surfaces fact sheet.

Open space design and LID practices are not limited to new construction. Most of the techniques can be done on existing developed land. For example, the cities of Maplewood and Burnsville both successfully incorporated a rain garden network into existing neighborhoods to capture street runoff, reducing the amount of runoff generated locally. In the case of Maplewood, this approach was chosen over more traditional curb and gutter installation. The LID approach can also be employed to comply with local regulations governing the volume, rate, and quality of runoff. See the Retrofitting: Infiltration, Filtration & Bioretention fact sheet for more information.

Open space development rules and ordinances

Development rules can be in conflict with alternate design standards that maximize the amount of open space associated with a development. Development rules can refer to subdivision codes, zoning regulations, parking and street standards and other local ordinances that regulate development. These rules will likely require review and adjustment to allow for open space design. Municipal fire, police and public works operations (ex. snow plowing) must be an integral part of the rule/ordinance planning so that their perspective is incorporated into any changes being considered.

The open space ordinance in the City of Inver Grove Heights’ Northwest Area (see page 8) requires 20 percent of upland buildable area (excluding area dedicated to stormwater treatment, protected wetlands, and other non-buildable space) to be maintained as undisturbed, natural area. In addition, the code allows an increased mixture of housing types for each zoning district in order to promote and enable cluster development to facilitate open space design.

Most local codes contain front yard setback requirements that dictate driveway length. In many communities, front yard setbacks for certain residential zoning categories may extend 50 or 100 feet or even longer, which increases driveway length well beyond what is needed for adequate parking and access to the garage. Shorter setbacks reduce the length and impervious cover for individual driveways. The Northwest Area of Inver Grove Heights, MN, allows a 20 foot setback.

The City of Lake Elmo city code introduces an option for additional units in its large lot residential zoning district. Additional units are allowed if total preserved open space represents at least 50 percent of the total buildable land area. Qualified preserved open space includes agricultural lands, natural habitat, pedestrian corridors, or neighborhood or community recreational areas. All preserved open space must be subject to a conservation easement.

Open space development in High density neighborhoods

One of the arguments against open space development is that it can only occur as part of high end, low density neighborhoods. Although new development with low density does offer the luxury of more options, it is not essential for open space development. EPA’s 2006 report entitled Protecting Water Resources with Higher-Density Development shows that high density development can actually lower per unit runoff because of such practices as shared infrastructure and multiple units under a single roof.

The City of Farmington, MN incorporated open space stormwater drainage design into a unique development with moderate densities. The development incorporates a prairie waterway in which open drainage ways were preserved in roadway medians, which route runoff to an adjacent stream while filtering it and allowing it to soak into the soil.

Maintenance considerations

Compared with natural open space, if lawn is preferred for open space, more maintenance is typically needed. Alternatively, open space can be easily maintained if planted with native grasses, forbs, shrubs and/or trees. If the latter approach is taken, the first two to three years will require weed control, but maintenance requirements will decrease with time. Once a LID best management practice is designed and installed properly, maintenance becomes essential to ensure that designed stormwater management performance and other benefits continue over the full life cycle of the installation. Maintenance and determining the responsible party(ies) for maintenance can be a stumbling block for LID. Responsible parties for maintenance should be mutually agreed upon by the homeowner and the MS4 early in the design process. The Minnesota Stormwater Manual contains advisory information on maintenance, as well as maintenance checklists. Some of the maintenance agreements and activities associated with LID practices are similar to those performed for conventional landscapes and stormwater systems; however, the scale, location, and the nature of an LID approach will require new maintenance strategies. Studies have shown that maintenance costs associated with LID are similar to traditional landscapes (Lakeville LID Study, 2006).

Typical cost

Open space development, having lower built acreage and imperviousness than conventional development, results in lower costs for grading, erosion control, stormwater and site infrastructure (Mohamed, 2006). Research has shown that on average, lots in subdivisions applying open space design (conservation subdivisions) carry a premium, are less expensive to build, and sell more rapidly than lots in conventional subdivisions (Mohamed, 2006; Zielinski 2001). Mohamed (2006) quantified the average savings at 💲7,400 per lot based on the results of 169 subdivisions.

A cost/benefit analysis was done in 2006 in the City of Lakeville, MN, on three alterative site designs: low impact development (LID), a conventionally designed development, and the actual built development which contained some LID components. Though the LID design was most profitable because of lower costs for stormwater infrastructure and thirty-year maintenance, the difference in profitability was not statistically significant. Therefore, both installation and long term maintenance costs can be said to be equal between the three designs.

The Green Values® Stormwater Calculator is a cost calculator that can help MS4s conduct cost/benefit analyses to optimize implementation of some of the open space design techniques discussed above.

This page was last edited on 23 January 2023, at 23:13.