Difference between revisions of "Calculating credits for bioretention"

m |

m |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

==Overview== | ==Overview== | ||

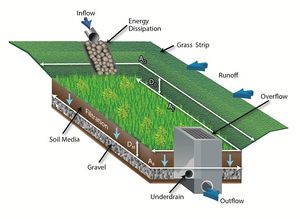

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:Biofiltration 1 for credit page.jpg|thumb|300px|alt=schematic showing bioinfiltration system|<font size=3>Schematic illustrating the components and processes for a bioinfiltration system.</font size>]] |

Biofiltration, commonly termed [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Bioretention bioretention] with underdrains, is primarily a stormwater quality control practice. Some water quantity reduction can be achieved through infiltration below the underdrain, particularly if the underdrain is raised above the bottom of the Best Management Practice (BMP), and through [[Glossary#E|evapotranspiration]]. | Biofiltration, commonly termed [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Bioretention bioretention] with underdrains, is primarily a stormwater quality control practice. Some water quantity reduction can be achieved through infiltration below the underdrain, particularly if the underdrain is raised above the bottom of the Best Management Practice (BMP), and through [[Glossary#E|evapotranspiration]]. | ||

Revision as of 16:43, 18 February 2015

This site is under construction. Anticipated completion date is March, 2015.

Credit refers to the quantity of stormwater or pollutant reduction achieved either by an individual BMP or cumulatively with multiple BMPs. Stormwater credits are a tool for local stormwater authorities who are interested in

- providing incentives to site developers to encourage the preservation of natural areas and the reduction of the volume of stormwater runoff being conveyed to a best management practice (BMP);

- complying with permit requirements, including antidegradation (see [1]; [2]);

- meeting the MIDS performance goal; or

- meeting or complying with water quality objectives, including Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Wasteload Allocations (WLAs).

This page provides a discussion of how biofiltration practices can achieve stormwater credits.

Contents

Overview

Biofiltration, commonly termed bioretention with underdrains, is primarily a stormwater quality control practice. Some water quantity reduction can be achieved through infiltration below the underdrain, particularly if the underdrain is raised above the bottom of the Best Management Practice (BMP), and through evapotranspiration.

Typically biofiltration consists of an engineered soil layer designed to treat stormwater runoff via filtration through plant and soil media, and evapotranspiration from plants. Pretreatment is REQUIRED for all biofiltration facilities to settle particulates before entering the BMP. Biofiltration includes an underdrain layer to collect the filtered runoff for downstream discharge. Other common components may include a stone aggregate layer to allow for increased retention storage and an impermeable liner on the bottom or sides of the facility if located near buildings, subgrade utilities, or in karst formations. Biofiltration is a versatile stormwater treatment method applicable to all types of settings such as landscaping islands, cul-de-sacs, parking lot margins, commercial setbacks, open space, rooftop drainage, and streetscapes.

Pollutant removal mechanisms

Biofiltration has one of the highest nutrient and pollutant removal efficiencies of any BMP (Mid-America Regional Council and American Public Works Association Manual of Best Management Practice BMPs for Stormwater Quality (2012). Biofiltration pollutant removal primarily occurs through filtering by the engineered soil media and vegetation. Biofiltration also provides pollutant removal and volume reduction through evaporation, infiltration, transpiration, biological and microbiological uptake, and soil adsorption; the extent of these benefits is highly dependent on site specific conditions and design. In addition to phosphorus and total suspended solids (TSS), which are discussed in greater detail below, biofiltration treats a wide variety of other pollutants.

Removal of phosphorus is dependent on the engineered media. Media mixes with high organic matter content typically leach phosphorus and can therefore contribute to water quality degradation. The Manual provides a detailed discussion of media mixes, including information on phosphorus retention.

Location in the treatment train

Stormwater treatment trains are multiple Best Management Practice (BMPs) that work together to minimize the volume of stormwater runoff, remove pollutants, and reduce the rate of stormwater runoff being discharged to Minnesota wetlands, lakes and streams. Under the Treatment Train approach, stormwater management begins with simple methods that prevent pollution from accumulating on the land surface, followed by methods that minimize the volume of runoff generated, and is completed by BMPs that reduce the pollutant concentration and/or volume of stormwater runoff. Biofiltration facilities are typically located in upland areas of the stormwater treatment train, controlling stormwater runoff close to the source.

Calculating credits

Biofiltration generates credits for Total Suspended Solids (TSS) and Total Phosphorus (TP). Biofiltration does not substantially reduce the volume of runoff but may qualify for a partial volume credit as a result of evapotranspiration, infiltration occurring through the sidewalls above the underdrain, and infiltration below the underdrain piping. Biofiltration is also effective at reducing concentrations of other pollutants including nitrogen, metals, bacteria, and hydrocarbons. This article does not provide information on calculating credits for pollutants other than TSS and TP, but references are provided that may be useful for calculating credits for other pollutants.

Assumptions and approach

In developing the credit calculations, it is assumed the bioretention practice is properly designed, constructed, and maintained in accordance with the Minnesota Stormwater Manual. If any of these assumptions is not valid, the BMP may not qualify for credits or credits should be reduced based on reduced ability of the BMP to achieve volume or pollutant reductions. For guidance on design, construction, and maintenance, see the appropriate article within the bioretention section of the Manual.

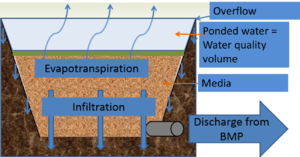

In the following discussion, the kerplunk method is assumed in calculating volume and pollutant reductions. This method assumes the water quality volume (WQV) is delivered instantaneously to the BMP. The WQV is stored as water ponded above the filter media and below the overflow point in the BMP. The WQV can vary depending on the stormwater management objective(s). For construction stormwater, the water quality volume is 1 inch off new impervious surface. For MIDS, the WQV is 1.1 inches.

In reality, some water will infiltrate through the bottom and sidewalls of the BMP as a rain event proceeds. The kerplunk method therefore may underestimate actual volume and pollutant losses.

Volume credit calculations

Volume credits for biofiltration are available only if the BMP permanently removes a portion of the stormwater runoff via infiltration through sidewalls or beneath the underdrain piping, or through evapotranspiration. These credits are assumed to be instantaneous values based on the design capacity of the BMP for a specific storm event. Instantaneous volume reduction, also termed event based volume reduction, can be converted to annual volume reduction percentages using the MIDS calculator or other appropriate modeling tools.

Volume credits for biofiltration basins with underdrains are calculated by a combination of infiltration through the unlined sides and bottom of the basin, the volume loss through evapotranspiration (ET), and the retention volume below the underdrain, if applicable (this is based on the assumption that this stored water will infiltrate into the underlying soil). The main design variables impacting the volume credits include whether the underdrain is elevated above the native soils and if an impermeable liner on the sides or bottom of the basin is used. Other design variables include surface area at overflow, media top surface area, underdrain location, and basin bottom locations, total depth of media, soil water holding capacity and media porosity, and infiltration rate of underlying soils.

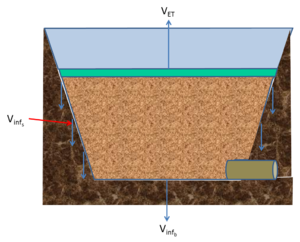

The volume credit (V) for biofiltration basins with underdrains, in cubic feet, is given by

\( V = V_{inf_b} + V_{inf_s} + V_{ET} + V_U \)

where:

- Vinfb = volume of infiltration through the bottom of the basin (cubic feet);

- Vinfs = volume of infiltration through the sides of the basin (cubic feet);

- VET = volume reduction due to evapotranspiration (cubic feet); and

- VU = volume of water stored beneath the underdrain that will infiltrate into the underlying soil (cubic feet).

Volume credits for infiltration through the bottom of the basin (Vinf_b) are accounted for only if the bottom of the basin is not lined. As long as water continues to draw down, some infiltration will occur through the bottom of the BMP. However, it is assumed that when an underdrain is included in the installation, the majority of water will be filtered through the media and exit through the underdrain. Because of this, the drawdown time is likely to be short. Volume credit for infiltration through the bottom of the basin is given by

\( V_{inf_B} = I_R/12 * A_B * DDT \)

where

- IR = design infiltration rate of underlying soil (inches per hour);

- AB = surface area at the bottom of the basin (square feet); and

- DDT = drawdown time for ponded water (hours).

If the kerplunk method is being applied and runoff water is delivered instantaneously to the BMP, the design infiltration rate (IR) will equal the saturated hydraulic conductivity. The drawdown time is typically a maximum of 48 hours, which is designed to be protective of plants grown in the media. The Construction Stormwater permit requires drawdown within 48 hours and recommends 24 hours when discharges are to a trout stream.

Volume credit for infiltration through the sides of the basin is accounted for only if the sides of the basin are not lined with an impermeable liner. Volume credit for infiltration through the sides of the basin is given by

\( V_{inf_s} = I_R/12 * (A_O - A_U) * DDT \)

where

- AO = the surface area at the overflow (square feet); and

- AU = the surface area at the underdrain (square feet).

This equation assumes water will infiltrate through the entire sideslope area during the period when water is being drawn down. This is not the case, however, since the water level will decline in the BMP. The MIDS calculator assumes a linear drop in water level and thus divides the right hand term in the above equation by 2.

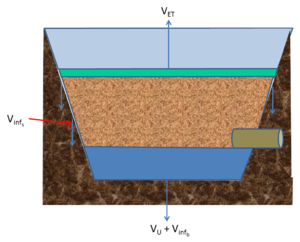

Volume credit for media storage capacity below the underdrain (VU) is accounted for only if the underdrain is elevated above the native soils. Volume credit for media storage capacity below the underdrain is given by

\( V_U = (A_U + A_B)/2 * n * D_U \)

where

- AB = surface area at the bottom of the media (square feet);

- n = media porosity (cubic feet per cubic foot); and

- DU = the depth of media below the underdrain (feet).

Per the kerplunk method, this is an instantaneous volume. This will somewhat overestimate actual storage when the majority of water is being captured by the underdrains. This equation also assumes this stored water will infiltrate into the underlying soil. Thus, using the entire porosity will overestimate the actual drainage. The MIDS calculator assumes water between the soil porosity and field capacity will infiltrate into the underlying soil.

The volume of water lost through ET is assumed to be the smaller of two calculated values: potential ET and measured ET. Potential ET (ETpot) is equal to the amount of water stored in the basin between field capacity and the wilting point. ETpot is converted to ET by multiplying by a factor of 0.5. Measured ET (ETmea) is the amount of water lost to ET as measured using available data and is assumed to be 0.2 inches/day. ET is considered to occur over a period equal to the drawdown time of the basin. Volume credit for evapotranspiration is given by the lesser of

\( ET_{mea} = 0.2/12 * A * 0.5 * t \) \( ET_{pot} = D * A * C_S \)

where

- t = time over which ET is occurring (hours);

- D = depth being considered (feet);

- A = area being considered (square feet); and

- CS = soil water available for ET.

Provided soil water content is greater than the wilting point, ET will continually occur during the non-frozen period. However, because the above volume calculations are event based, t will be equal to the time between rain events. In the MIDS calculator, a value of 3 days is used because this is the average number of days between precipitation events. ET will occur over the entire media depth. D may therefore be set equal to the media depth (DM). In this case, the value for A would be the average area through the entire depth of the media. The MIDS calculator limits ET to the area above the underdrain. If infiltration is being computed through the bottom and sidewalls of the basin, then CS would be field capacity minus the wilting point of soils (cubic feet per cubic foot) since water above the field capacity would infiltrate (or go to an underdrain).

The volume of water passing through underdrains can be determined by subtracting the volume loss (V) from the volume of water instantaneously captured by the BMP. No volume reduction credit is given for filtered stormwater that exits through the underdrain, but the volume of filtered water can be used in the calculation of pollutant removal credits through filtration.

The volume reduction credit (V) can be converted to an annual volume if desired. This conversion can be generated using the MIDS calculator or other appropriate modeling techniques. The MIDS calculator obtains the percentage annual volume reduction through performance curves developed from multiple modeling scenarios using the volume reduction capacity for biofiltration, the infiltration rate of the underlying soils, and the contributing watershed size and imperviousness.

Total suspended solids credit calculations

TSS reduction credits correspond with volume reduction through infiltration and filtration of water captured by the biofiltration basin and are given by

\( M_{TSS} = M_{TSS_i} + M_{TSS_f} \)

where

- MTSS = TSS removal (pounds);

- MTSS_i = TSS removal from infiltrated water (pounds); and

- MTSS_f = TSS removal from filtered water (pounds).

Pollutant removal for infiltrated water is assumed to be 100 percent. The mass of pollutant removed through infiltration, in pounds, is given by

\( M_{TSS_i} = 0.0000624 * (V_{inf_b} + V_{inf_s} + V_U) * EMC_{TSS} \)

where

- EMCTSS is the event mean TSS concentration in runoff water entering the BMP (milligrams per liter).

The EMCTSS entering the BMP is a function of the contributing land use and treatment by upstream tributary BMPs.

Removal for the filtered portion is less than 100 percent. The Stormwater Manual provides a recommended value of 85 percent removal for filtered water, while the MIDS calculator provides a value of 65 percent. Alternate justified percentages for TSS removal can be used if proven to be applicable to the BMP design.

The mass of pollutant removed through filtration, in pounds, is given by

\( M_{TSS_f} = 0.0000624 * (V_{total} - (V_{inf_b} + V_{inf_s} + V_U)) * EMC_{TSS} * R_{TSS} \)

where

- Vtotal is the total volume of water captured by the BMP (cubic feet); and

- RTSS is the TSS pollutant removal percentage for filtered runoff. Alternate justified percentages for TSS removal, including direct monitoring data, can be used if proven to be applicable to BMP credit calculation.

The above calculations may be applied on an event or annual basis using the appropriate units.

Total phosphorus credit calculations

Total phosphorus (TP) reduction credits correspond with volume reduction through infiltration and filtration of water captured by the biofiltration basin and are given by

\( M_{TP} = M_{TP_i} + M_{TP_f} \)

where

- MTP = TP removal (pounds);

- MTP_i = TP removal from infiltrated water (pounds); and

- MTP_f = TP removal from filtered water (pounds).

Pollutant removal for infiltrated water is assumed to be 100 percent. The mass of pollutant removed through infiltration, in pounds, is given by

\( M_{TP_i} = 0.0000624 * (V_{inf_b} + V_{inf_s} + V_U) * EMC_{TP} \)

where

- EMCTP is the event mean TP concentration in runoff water entering the BMP (milligrams per liter).

The EMCTP entering the BMP is a function of the contributing land use and treatment by upstream tributary BMPs.

The filtration credit for TP in biofiltration with underdrains assumes removal rates based on the soil media mix used and the presence or absence of amendments. Soil mixes with more than 30 mg/kg phosphorus (P) content are likely to leach phosphorus and do not qualify for a water quality credit. If the soil phosphorus concentration is less than 30 mg/kg, the mass of phosphorus removed through filtration, in pounds, is given by

\( M_{TP_f} = 0.0000624 * (V_{total} - (V_{inf_b} + V_{inf_s} + V_U)) * EMC_{TP} * R_{TP} \)

Again, assuming the phosphorus content in the media is less than 30 milligrams per kilogram, the removal efficiency (RTP) provided in the Stormwater Manual is a function of the fraction of phosphorus that is in particulate or dissolved form, the depth of the media, and the presence or absence of soil amendments. For the purpose of calculating credits it can be assumed that TP in storm water runoff consists of 55 percent particulate phosphorus (PP) and 45 percent dissolved phosphorus (DP). The removal efficiency for particulate phosphorus is 80 percent. The removal efficiency for dissolved phosphorus is 20 percent if the media depth is 2 feet or greater. The efficiency decreases by 1 percent for each 0.1 foot decrease in media thickness below 2 feet. If a soil amendment is added to the BMP design, an additional 40 percent credit is applied to dissolved phosphorus. Thus, the overall removal efficiency, (RTP), expressed as a percent removal of total phosphorus, is given by

\( R_{TP} = [0.8 * 0.55] + [0.45 * ((0.2 * (D_{MU_{max=2}})/2) + 0.40_{if amendment is used})] * 100 \)

where

- the first term on the right side of the equation represents the removal of particulate phosphorus;

- the second term on the right side of the equation represents the removal of dissolved phosphorus; and

- DMUmax=2 = the media depth above the underdrain, up to a maximum of 2 feet.

Methods for calculating credits

This section provides specific information on generating and calculating credits from biofiltration for volume, Total Suspended Solids (TSS) and Total Phosphorus (TP). Stormwater runoff volume and pollution reductions (“credits”) may be calculated using one of the following methods:

- Quantifying volume and pollution reductions based on accepted hydrologic models

- MIDS Calculator approach

- Quantifying volume and pollution reductions based on values reported in literature

- Quantifying volume and pollution reductions based on field measurements

Credits based on models

Users may opt to use a water quality model or calculator to compute volume, TSS and/or TP pollutant removal for the purpose of determining credits for biofiltration. The available models described in the following sections are commonly used by water resource professionals, but are not explicitly endorsed or required by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency.

Use of models or calculators for the purpose of computing pollutant removal credits should be supported by detailed documentation, including:

- Model name and version

- Date of analysis

- Person or organization conducting analysis

- Detailed summary of input data

- Calibration and verification information

- Detailed summary of output data

The following table lists water quantity and water quality models that are commonly used by water resource professionals to predict the hydrologic, hydraulic, and/or pollutant removal capabilities of a single or multiple stormwater BMPs. The table can be used to guide a user in selecting the most appropriate model for computing volume, TSS, and/or TP removal for biofiltration BMPs.

Comparison of stormwater models and calculators. Additional information and descriptions for some of the models listed in this table can be found at this link. Note that the Construction Stormwater General Permit requires the water quality volume to be calculated as an instantaneous volume, meaning several of these models cannot be used to determine compliance with the permit.

Link to this table

Access this table as a Microsoft Word document: File:Stormwater Model and Calculator Comparisons table.docx.

| Model name | BMP Category | Assess TP removal? | Assess TSS removal? | Assess volume reduction? | Comments | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constructed basin BMPs | Filter BMPs | Infiltrator BMPs | Swale or strip BMPs | Reuse | Manu- factured devices |

|||||

| Center for Neighborhood Technology Green Values National Stormwater Management Calculator | X | X | X | X | No | No | Yes | Does not compute volume reduction for some BMPs, including cisterns and tree trenches. | ||

| CivilStorm | Yes | Yes | Yes | CivilStorm has an engineering library with many different types of BMPs to choose from. This list changes as new information becomes available. | ||||||

| EPA National Stormwater Calculator | X | X | X | No | No | Yes | Primary purpose is to assess reductions in stormwater volume. | |||

| EPA SWMM | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | User defines parameter that can be used to simulate generalized constituents. | |||

| HydroCAD | X | X | X | No | No | Yes | Will assess hydraulics, volumes, and pollutant loading, but not pollutant reduction. | |||

| infoSWMM | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | User defines parameter that can be used to simulate generalized constituents. | |||

| infoWorks ICM | X | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| i-Tree-Hydro | X | No | No | Yes | Includes simple calculator for rain gardens. | |||||

| i-Tree-Streets | No | No | Yes | Computes volume reduction for trees, only. | ||||||

| LSPC | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | Though developed for HSPF, the USEPA BMP Web Toolkit can be used with LSPC to model structural BMPs such as detention basins, or infiltration BMPs that represent source control facilities, which capture runoff from small impervious areas (e.g., parking lots or rooftops). | |||

| MapShed | X | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | Region-specific input data not available for Minnesota but user can create this data for any region. | ||

| MCWD/MWMO Stormwater Reuse Calculator | X | Yes | No | Yes | Computes storage volume for stormwater reuse systems | |||||

| Metropolitan Council Stormwater Reuse Guide Excel Spreadsheet | X | No | No | Yes | Computes storage volume for stormwater reuse systems. Uses 30-year precipitation data specific to Twin Cites region of Minnesota. | |||||

| MIDS Calculator | X | X | X | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | Includes user-defined feature that can be used for manufactured devices and other BMPs. |

| MIKE URBAN (SWMM or MOUSE) | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | User defines parameter that can be used to simulate generalized constituents. | |||

| P8 | X | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| PCSWMM | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | User defines parameter that can be used to simulate generalized constituents. | |||

| PLOAD | X | X | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | No | User-defined practices with user-specified removal percentages. | |

| PondNet | X | Yes | No | Yes | Flow and phosphorus routing in pond networks. | |||||

| PondPack | X | [ | No | No | Yes | PondPack can calculate first-flush volume, but does not model pollutants. It can be used to calculate pond infiltration. | ||||

| RECARGA | X | No | No | Yes | ||||||

| SHSAM | X | No | Yes | No | Several flow-through structures including standard sumps, and proprietary systems such as CDS, Stormceptors, and Vortechs systems | |||||

| SUSTAIN | X | X | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | Categorizes BMPs into Point BMPs, Linear BMPs, and Area BMPs | |

| SWAT | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | Model offers many agricultural BMPs and practices, but limited urban BMPs at this time. | |||

| Virginia Runoff Reduction Method | X | X | X | X | X | X | Yes | No | Yes | Users input Event Mean Concentration (EMC) pollutant removal percentages for manufactured devices. |

| WARMF | X | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | Includes agriculture BMP assessment tools. Compatible with USEPA Basins | ||||

| WinHSPF | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | USEPA BMP Web Toolkit available to assist with implementing structural BMPs such as detention basins, or infiltration BMPs that represent source control facilities, which capture runoff from small impervious areas (e.g., parking lots or rooftops). | |||

| WinSLAMM | X | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| XPSWMM | X | X | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | User defines parameter that can be used to simulate generalized constituents. | |||

MIDS Calculator

The Minimal Impact Design Standards (MIDS) best management practice (BMP) calculator is a tool used to determine stormwater runoff volume and pollutant reduction capabilities of various low impact development (LID) BMPs. The MIDS calculator estimates the stormwater runoff volume reductions for various BMPs and annual pollutant load reductions for total phosphorus (including a breakdown between particulate and dissolved phosphorus) and total suspended solids (TSS). The calculator was intended for use on individual development sites, though capable modelers could modify its use for larger applications.

The MIDS calculator is designed in Microsoft Excel with a graphical user interface (GUI), packaged as a windows application, used to organize input parameters. The Excel spreadsheet conducts the calculations and stores parameters, while the GUI provides a platform that allows the user to enter data and presents results in a user-friendly manner.

Detailed guidance has been developed for all BMPs in the calculator, including biofiltration. An overview of individual input parameters and workflows is presented in the MIDS Calculator User Documentation.

Credits based on reported literature values

A simplified approach to computing a credit would be to apply a reduction value found in literature to the pollutant mass load or concentration (EMC) of the biofiltration device. A more detailed explanation of the differences between mass load reductions and concentration (EMC) reductions can be found on the pollutant removal page of this WIKI (here). Designers may use the pollutant reduction values reported in this WIKI (here) or may research values from other databases and published literature. Designers who opt for this approach should:

- Select the median value from pollutant reduction databases that report a range of reductions, such as from the International BMP Database.

- Select a pollutant removal reduction from literature that studied a biofiltration device with site characteristics and climate similar to the device being considered for credits.

- When using data from an individual study, review the article to determine that the design principles of the studied biofiltration are close to the design recommendations for Minnesota, as described in this WIKI, and/or by a local permitting agency.

- Preference should be given to literature that has been published in a peer-reviewed publication.

Credits based on field monitoring

Field monitoring may be used to calculate stormwater credits in lieu of desktop calculations or models/calculators as described. Careful planning is HIGHLY RECOMMENDED before commencing a program to monitor the performance of a BMP. The general steps involved in planning and implementing BMP monitoring include the following.

- Establish the objectives and goals of the monitoring.

- Which pollutants will be measured?

- Will the monitoring study the performance of a single BMP or multiple BMPs?

- Are there any variables that will affect the BMP performance? Variables could include design approaches, maintenance activities, rainfall events, rainfall intensity, etc.

- Will the results be compared to other BMP performance studies?

- What should be the duration of the monitoring period? Is there a need to look at the annual performance vs the performance during a single rain event? Is there a need to assess the seasonal variation of BMP performance?

- Plan the field activities. Field considerations include:

- Equipment selection and placement

- Sampling protocols including selection, storage, delivery to the laboratory

- Laboratory services

- Health and Safety plans for field personnel

- Record keeping protocols and forms

- Quality control and quality assurance protocols

- Execute the field monitoring

- Analyze the results

The following guidance manuals have been developed to assist BMP owners and operators on how to plan and implement BMP performance monitoring.

Geosyntec Consultants and Wright Water Engineers prepared this guide in 2009 with support from the USEPA, Water Environment Research Foundation, Federal Highway Administration, and the Environment and Water Resource Institute of the American Society of Civil Engineers. This guide was developed to improve and standardize the protocols for all BMP monitoring and to provide additional guidance for Low Impact Development (LID) BMP monitoring. Highlighted chapters in this manual include:

- Chapter 2: Designing the Program

- Chapters 3 & 4: Methods and Equipment

- Chapters 5 & 6: Implementation, Data Management, Evaluation and Reporting

- Chapter 7: BMP Performance Analysis

- Chapters 8, 9, & 10: LID Monitoring

AASHTO (American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials) and the FHWA (Federal Highway Administration) sponsored this 2006 research report, which was authored by Oregon State University, Geosyntec Consultants, the University of Florida, and the Low Impact Development Center. The primary purpose of this report is to advise on the selection and design of BMPs that are best suited for highway runoff. The document includes the following chapters on performance monitoring that may be a useful reference for BMP performance monitoring, especially for the performance assessment of a highway BMP:

- Chapter 4: Stormwater Characterization

- 4.2: General Characteristics and Pollutant Sources

- 4.3: Sources of Stormwater Quality data

- Chapter 8: Performance Evaluation

- 8.1: Methodology Options

- 8.5: Evaluation of Quality Performance for Individual BMPs

- 8.6: Overall Hydrologic and Water Quality Performance Evaluation

- Chapter 10: Hydrologic Evaluation

- 10.5: Performance Verification and Design Optimization

In 2014 the Water Environment Federation released this White Paper that investigates the feasibility of a national program for the testing of stormwater products and practices. The information contained in this White Paper would be of use to those considering the monitoring of a manufactured BMP. The report does not include any specific guidance on the monitoring of a BMP, but it does include a summary of the existing technical evaluation programs that could be consulted for testing results for specific products (see Table 1 on page 8).

The most current version of this manual was released by the State of California, Department of Transportation in November 2013. As with the other monitoring manuals described, this manual does include guidance on planning a stormwater monitoring program. However, this manual is among the most thorough for field activities. Relevant chapters include:

- Chapter 4: Monitoring Methods and Equipment

- Chapter 5: Analytical Methods and Laboratory Selection

- Chapter 6: Monitoring Site Selection

- Chapter 8: Equipment Installation and Maintenance

- Chapter 10: Pre-Storm Preparation

- Chapter 11: Sample Collection and Handling

- Chapter 12: Quality Assurance / Quality Control

- Chapter 13: Laboratory Reports and Data Review

- Chapter 15: Gross Solids Monitoring

This online manual was developed in 2010 by Andrew Erickson, Peter Weiss, and John Gulliver from the University of Minnesota and St. Anthony Falls Hydraulic Laboratory with funding provided by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. The manual advises on a four-level process to assess the performance of a Best Management Practice, involving:

- Level 1: Visual Inspection

- Level 2: Capacity Testing

- Level 3: Synthetic Runoff Testing

- Level 4: Monitoring

- Level 1 activities do not produce numerical performance data that could be used to obtain a stormwater management credit. BMP owners and operators who are interested in using data obtained from Levels 2 and 3 should consult with the MPCA or other regulatory agency to determine if the results are appropriate for credit calculations. Level 4, Monitoring, is the method most frequently used for assessment of the performance of a BMP.

Use these links to obtain detailed information on the following topics related to BMP performance monitoring:

- Water Budget Measurement

- [Sampling Methods http://stormwaterbook.safl.umn.edu/content/sampling-methods]

- [Analysis of Water and Soils http://stormwaterbook.safl.umn.edu/content/analysis-water-and-soils]

- [Data Analysis for Monitoring http://stormwaterbook.safl.umn.edu/content/monitoring-data-analysis]

Other pollutants

In addition to TSS and phosphorus, constructed basins can reduce loading of other pollutants. According to the International Stormwater Database, studies have shown that biofiltration BMPs are effective at reducing concentrations of pollutants, including metals, and bacteria. A compilation of the pollutant removal capabilities from a review of literature are summarized below.

Relative pollutant reduction from bioretention systems for metals, nitrogen, bacteria, and organics.

Link to this table

| Pollutant | Constituent | Treatment capabilities1 |

|---|---|---|

| Metals2 | Cadmium, Chromium, Copper, Zinc, Lead | High |

| Nitrogen2 | Total nitrogen, Total Kjeldahl nitrogen | Low/medium |

| Bacteria2 | Fecal coliform, e. coli | High |

| Organics | Petroleum hydrocarbons3, Oil/grease4 | High |

1 Low: < 30%; Medium: 30 to 65%; High: >65%

2 International Stormwater Database, (2012)

3 LeFevre et al., (2012)

4 Hsieh and Davis (2005).

See Reference list

References

- Brown, Robert A., and William F. Hunt III. 2010. Impacts of media depth on effluent water quality and hydrologic performance of undersized bioretention cells. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering 137, no. 3: 132-143.

- Brown, R. A., and W. F. Hunt. 2011. Underdrain configuration to enhance bioretention exfiltration to reduce pollutant loads. Journal of Environmental Engineering 137, no. 11: 1082-1091.

- Bureau of Environmental Services. 2006. Effectiveness Evaluation of Best Management Practices for Stormwater Management in Portland. Oregon. Bureau of Environmental Services, Portland, Oregon.

- California Stormwater Quality Association. 2003. California Stormwater BMP Handbook-New Development and Redevelopment. California Stormwater Quality Association, Menlo Park, CA.

- Chris, Denich, Bradford Andrea, and Drake Jennifer. 2013. Bioretention: assessing effects of winter salt and aggregate application on plant health, media clogging and effluent quality. Water Quality Research Journal of Canada. 48(4):387.

- Caltrans. 2004. BMP Retrofit Pilot Program Final Report. Report No. CTSW-RT-01-050. Division of Environmental Analysis. California Dept. of Transportation, Sacramento, CA.

- CDM Smith. 2012. Omaha Regional Stormwater Design Manual. Chapter 8 Stormwater Best Management Practices. Kansas City, MO.

- Davis, Allen P., Mohammad Shokouhian, Himanshu Sharma, and Christie Minami. 2001. Laboratory study of biological retention for urban stormwater management. Water Environment Research, 73, no. 1:5-14.

- Davis, Allen P., Mohammad Shokouhian, Himanshu Sharma, and Christie Minami. 2006. Water quality improvement through bioretention media: Nitrogen and phosphorus removal. Water Environment Research 78, no. 3: 284-293.

- Davis, Allen P., Mohammad Shokouhian, Himanshu Sharma, Christie Minami, and Derek Winogradoff. 2003. Water quality improvement through bioretention: Lead, copper, and zinc removal. Water Environment Research 75, no. 1: 73-82.

- DiBlasi, Catherine J., Houng Li, Allen P. Davis, and Upal Ghosh. 2008. Removal and fate of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon pollutants in an urban stormwater bioretention facility. Environmental science & technology 43, no. 2: 494-502.

- Dorman, M. E., H. Hartigan, F. Johnson, and B. Maestri. 1988. Retention, detention, and overland flow for pollutant removal from highway stormwater runoff: interim guidelines for management measures. Final report, September 1985-June 1987. No. PB-89-133292/XAB. Versar, Inc., Springfield, VA (USA).

- Geosyntec Consultants and Wright Water Engineers. 2009. Urban Stormwater BMP Performance Monitoring. Prepared under Support from U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Water Environment Research Foundation, Federal Highway Administration, Environmental and Water Resource Institute of the American Society of Civil Engineers.

- Gulliver, J. S., A. J. Erickson, and P.T. Weiss. 2010. safl. umn. edu Stormwater treatment: Assessment and maintenance. University of Minnesota, St. Anthony Falls Laboratory. Minneapolis, MN.

- Hathaway, J. M., W. F. Hunt, and S. Jadlocki. 2009. Indicator bacteria removal in storm-water best management practices in Charlotte, North Carolina. Journal of Environmental Engineering 135, no. 12: 1275-1285.

- Hong, Eunyoung, Eric A. Seagren, and Allen P. Davis. 2006. Sustainable oil and grease removal from synthetic stormwater runoff using bench-scale bioretention studies. Water Environment Research 78, no. 2: 141-155.

- Hsieh, Chi-hsu, and Allen P. Davis. 2005. Evaluation and optimization of bioretention media for treatment of urban storm water runoff. Journal of Environmental Engineering 131, no. 11: 1521-1531.

- Hunt, W. F., A. R. Jarrett, J. T. Smith, and L. J. Sharkey. 2006. Evaluating bioretention hydrology and nutrient removal at three field sites in North Carolina. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering 132, no. 6: 600-608.

- Jaffe, et. al. 2010. The Illinois Green Infrastructure Study. Prepared by the University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning. Center for Neighborhood Technology, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant College Program.

- Jurries, Dennis. 2003. Biofilters (Bioswales, Vegetative Buffers, & Constructed Wetlands) for Storm Water Discharge Pollution Removal. Quality, State of Oregon, Department of Environmental Quality (Ed.).

- Lefevre G.H., Hozalski R.M., Novak P. 2012. The role of biodegradation in limiting the accumulation of petroleum hydrocarbons in raingarden soil. Water Res. 46(20):6753-62.

- Leisenring, M., J. Clary, and P. Hobson. 2012. International Stormwater Best Management Practices (BMP) Database Pollutant Category Summary Statistical Addendum: TSS, Bacteria, Nutrients, and Metals. July: 1-31.

- Li, Houng, and Allen P. Davis. 2009. Water quality improvement through reductions of pollutant loads using bioretention. Journal of Environmental Engineering 135, no. 8: 567-576.

- Komlos, John, and Robert G. Traver. 2012. Long-term orthophosphate removal in a field-scale storm-water bioinfiltration rain garden. Journal of Environmental Engineering 138, no. 10: 991-998.

- Mid-America Regional Council, and American Public Works Association. 2012. Manual of best management practices for stormwater quality.

- New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services. 2008. New Hampshire Stormwater Manual. Volume 2 Appendix B. Concord, NH.

- North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources. 2007. Stormwater Best Management Practices Manual. North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Raleigh, North Carolina.

- Passeport, Elodie, William F. Hunt, Daniel E. Line, Ryan A. Smith, and Robert A. Brown. 2009. Field study of the ability of two grassed bioretention cells to reduce storm-water runoff pollution. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering 135, no. 4: 505-510.

- Oregon State University Transportation Officials. Dept. of Civil, Environmental Engineering, University of Florida. Dept. of Environmental Engineering Sciences, GeoSyntec Consultants, and Low Impact Development Center, Inc. 2006. Evaluation of Best Management Practices for Highway Runoff Control. No. 565. Transportation Research Board.

- Schueler, T.R., Kumble, P.A., and Heraty, M.A. 1992. A Current Assessment of Urban Best Management Practices: Techniques for Reducing Non-Point Source Pollution in the Coastal Zone. Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, Washington, D.C.

- TetraTech. 2008. BMP Performance Analysis. Prepared for US EPA Region 1, Boston, MA.

- Torres, Camilo. 2010. Characterization and Pollutant Loading Estimation for Highway Runoff in Omaha, Nebraska. M.S. Thesis, University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

- United States EPA. 1999. Stormwater technology fact sheet-bioretention. Office of Water, EPA 832-F-99 12.

- Water Environment Federation. 2014. Investigation into the Feasibility of a National Testing and Evaluation Program for Stormwater Products and Practices. A White Paper by the National Stormwater Testing and Evaluation of Products and Practices (STEPP) Workgroup Steering Committee.

- WEF, ASCE/EWRI. 2012. Design of Urban Stormwater Controls. WEF Manual of Practice No. 23, ASCE/EWRI Manuals and Reports on Engineering Practice No. 87. Prepared by the Design of Urban Stormwater Controls Task Forces of the Water Environment Federation and the American Society of Civil Engineers/Environmental & Water Resources Institute.

- Weiss, Peter T., John S. Gulliver, and Andrew J. Erickson. 2005. The Cost and Effectiveness of Stormwater Management Practices Final Report.. Published by: Minnesota Department of Transportation .

- Wossink, G. A. A., and Bill Hunt. 2003. The economics of structural stormwater BMPs in North Carolina. Water Resources Research Institute of the University of North Carolina.