Difference between revisions of "Biochar and applications of biochar in stormwater management"

m (→References) |

m (added links to subtitled videos on youtube) |

||

| (20 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Technical information page image.png|thumb|left|100px|alt=image]] | [[File:Technical information page image.png|thumb|left|100px|alt=image]] | ||

| + | [[File:Biochar page navigation.mp4|thumb|left|200px|alt=link to video for navigating this page|<font size=3>3-minute video summarizing content and navigation for this page ([https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2aLTbA4uLG4 click here for subtitled version])</font size>]] | ||

[[file:Check it out.png|200px|thumb|left|alt=check it out image|<font size=3>Check out this video on [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6HlJHAVT0sY using biochar to rebuild urban soils] or this video on [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RXMUmby8PpU making biochar]</font size>]] | [[file:Check it out.png|200px|thumb|left|alt=check it out image|<font size=3>Check out this video on [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6HlJHAVT0sY using biochar to rebuild urban soils] or this video on [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RXMUmby8PpU making biochar]</font size>]] | ||

| Line 33: | Line 34: | ||

This page provides information on biochar. While providing extensive information on biochar, there is [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#Applications_for_biochar_in_stormwater_management a section focused specifically on stormwater applications for biochar]. | This page provides information on biochar. While providing extensive information on biochar, there is [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#Applications_for_biochar_in_stormwater_management a section focused specifically on stormwater applications for biochar]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <font size=5>[[Engineered (bioretention) media organic material properties and specifications|'''Link to a table comparing properties of different organic materials''']]</font size> | ||

==Overview and description== | ==Overview and description== | ||

| Line 79: | Line 82: | ||

Recommended reading | Recommended reading | ||

| − | * | + | *Emerging Best Management Practices in Stormwater: Biochar as Filtration Media - Pacific Northwest Pollution Prevention Resource Center |

*[https://www.deeproot.com/blog/blog-entries/improving-stormwater-control-measure-performance-with-biochar Improving Stormwater Control Measure Performance with Biochar] - Deeproot | *[https://www.deeproot.com/blog/blog-entries/improving-stormwater-control-measure-performance-with-biochar Improving Stormwater Control Measure Performance with Biochar] - Deeproot | ||

*[http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/IDEA/FinalReports/Highway/NCHRP182_Final_Report.pdf Reducing Stormwater Runoff and Pollutant Loading with Biochar Addition to Highway Greenways] - Final Report for NCHRP IDEA Project 182 | *[http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/IDEA/FinalReports/Highway/NCHRP182_Final_Report.pdf Reducing Stormwater Runoff and Pollutant Loading with Biochar Addition to Highway Greenways] - Final Report for NCHRP IDEA Project 182 | ||

| Line 96: | Line 99: | ||

*High ash biochars, such as manures and coffee husk, exhibit higher <span title="A measure of how many cations can be retained on soil particle surfaces"> '''cation exchange capacity'''</span>, which may increase nutrient capture, although high initial nutrient concentrations may offset this and even contribute to nutrient loss. | *High ash biochars, such as manures and coffee husk, exhibit higher <span title="A measure of how many cations can be retained on soil particle surfaces"> '''cation exchange capacity'''</span>, which may increase nutrient capture, although high initial nutrient concentrations may offset this and even contribute to nutrient loss. | ||

| − | The [https://biochar-international.org/ | + | The [https://biochar-international.org/ International Biochar Initiative (see Appendix 6)] provides a classification system for biochar feedstocks, shown below. |

*Unprocessed Feedstock Types | *Unprocessed Feedstock Types | ||

**Rice hulls & straw | **Rice hulls & straw | ||

| Line 200: | Line 203: | ||

Biochar may have several properties for managing stormwater, such as increased water and pollutant retention, improving soil physical properties, and attenuating bacteria and pathogens. Biochar has been examined as a potential amendment to <span title="Engineered media is a mixture of sand, fines (silt, clay), and organic matter utilized in stormwater practices, most frequently in bioretention practices. The media is typically designed to have a rapid infiltration rate, attenuate pollutants, and allow for plant growth."> [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Design_criteria_for_bioretention#Materials_specifications_-_filter_media '''engineered media''']</span> in bioretention or other stormwater control practices. With respect to phosphorus, information from the literature is mixed. Below are summaries from several studies. | Biochar may have several properties for managing stormwater, such as increased water and pollutant retention, improving soil physical properties, and attenuating bacteria and pathogens. Biochar has been examined as a potential amendment to <span title="Engineered media is a mixture of sand, fines (silt, clay), and organic matter utilized in stormwater practices, most frequently in bioretention practices. The media is typically designed to have a rapid infiltration rate, attenuate pollutants, and allow for plant growth."> [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Design_criteria_for_bioretention#Materials_specifications_-_filter_media '''engineered media''']</span> in bioretention or other stormwater control practices. With respect to phosphorus, information from the literature is mixed. Below are summaries from several studies. | ||

| − | *[https:/ | + | *[https://wrc.umn.edu/biofiltration-media-opt-phase2 Erickson et al.] observed phosphorus release from media that included 15% biochar and 20% leaf compost. This research is continuing and initial results suggest phosphorus release also occurs with 10% compost. |

*[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Mohanty et al.] (2018) observed that biochar does not absorb phosphate efficiently. Phosphorus retention can be enhanced by impregnating biochar with cations such as magnesium and zinc. | *[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Mohanty et al.] (2018) observed that biochar does not absorb phosphate efficiently. Phosphorus retention can be enhanced by impregnating biochar with cations such as magnesium and zinc. | ||

*[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Reddy et al.] (2014) found that biochar reduced influent phosphate concentrations by 47% in column experiments. Influent concentrations were 0.57 and 0.82 mg/L for unwashed and washed biochar, respectively. These concentrations are on the high end of concentrations found in urban stormwater. | *[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Reddy et al.] (2014) found that biochar reduced influent phosphate concentrations by 47% in column experiments. Influent concentrations were 0.57 and 0.82 mg/L for unwashed and washed biochar, respectively. These concentrations are on the high end of concentrations found in urban stormwater. | ||

| Line 270: | Line 273: | ||

*Quilliam, R. S., Marsden, K. A., Gertler, C., Rousk, J., DeLuca, T. H. and Jones, D. L. 2012. ''Nutrient dynamics, microbial growth and weed emergence in biochar amended soil are influenced by time since application and reapplication rate''. Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Environment. 158:192–199. | *Quilliam, R. S., Marsden, K. A., Gertler, C., Rousk, J., DeLuca, T. H. and Jones, D. L. 2012. ''Nutrient dynamics, microbial growth and weed emergence in biochar amended soil are influenced by time since application and reapplication rate''. Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Environment. 158:192–199. | ||

*Schultz, H. and Glaser, B. 2012. Effects of biochar compared to organic and inorganic fertilizers on soil quality and plant growth in a greenhouse experiment. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 175:410–422. | *Schultz, H. and Glaser, B. 2012. Effects of biochar compared to organic and inorganic fertilizers on soil quality and plant growth in a greenhouse experiment. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 175:410–422. | ||

| − | *Yoo, G. and Kang, H. 2010. | + | *Yoo, G. and Kang, H. 2010. ''Effects of biochar addition on greenhouse gas emissions and microbial responses in a short-term laboratory experiment''. Journal of Environmental Quality. 41:1193–1202. |

==Standards, classification, testing, and distributors== | ==Standards, classification, testing, and distributors== | ||

| Line 282: | Line 285: | ||

===Biochar standards=== | ===Biochar standards=== | ||

| − | The Internation Biochar Initiative (IBI) developed Standardized Product Definition and Product Testing Guidelines for Biochar That Is Used in Soil, also referred to The Biochar Standards. These standards provide guidelines and is not a formal set of industry specifications. The goal of The Biochar Standards is to "universally and consistently define what biochar is, and to confirm that a product intended for sale or use as biochar possesses the necessary characteristics for safe use. The IBI Biochar Standards also provide common reporting requirements for biochar that will aid researchers in their ongoing efforts to link specific functions of biochar to its beneficial soil and crop impacts." The IBI also provides a certification program. Information on the standards and certification are found on [https://biochar-international.org/characterizationstandard/ International Biochar Institute's website] or at the [https://www.biochar-international.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/IBI_Biochar_Standards_V2.1_Final.pdf IBI's Standardized Product Definition and Product Testing Guidelines for Biochar That Is Used in Soil]. | + | The Internation Biochar Initiative (IBI) developed ''Standardized Product Definition and Product Testing Guidelines for Biochar That Is Used in Soil'', also referred to ''The Biochar Standards''. These standards provide guidelines and is not a formal set of industry specifications. The goal of ''The Biochar Standards'' is to "universally and consistently define what biochar is, and to confirm that a product intended for sale or use as biochar possesses the necessary characteristics for safe use. The IBI Biochar Standards also provide common reporting requirements for biochar that will aid researchers in their ongoing efforts to link specific functions of biochar to its beneficial soil and crop impacts." The IBI also provides a certification program. Information on the standards and certification are found on [https://biochar-international.org/characterizationstandard/ International Biochar Institute's website] or at the [https://www.biochar-international.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/IBI_Biochar_Standards_V2.1_Final.pdf IBI's Standardized Product Definition and Product Testing Guidelines for Biochar That Is Used in Soil]. |

The IBI also provides [https://biochar-international.org/biochar-classification-tool/ a biochar classification tool]. Currently, four biochar properties are classified: | The IBI also provides [https://biochar-international.org/biochar-classification-tool/ a biochar classification tool]. Currently, four biochar properties are classified: | ||

| Line 296: | Line 299: | ||

===Test methods=== | ===Test methods=== | ||

| − | There is no universally accepted standard for biochar testing. The International Biochar Initiative (IBI) developed [https:// | + | There is no universally accepted standard for biochar testing. The International Biochar Initiative (IBI) developed [https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Standardized-Product-Definition-and-Product-Testing-Ibi/d7f179afe9080d86b27be014109d4ebbd4b46a1b Standardized Product Definition and Product Testing Guidelines for Biochar That Is Used in Soil]. The goals of this document are to provide "stakeholders and 5 commercial entities with standards to identify certain qualities and characteristics of biochar materials according to relevant, reliable, and measurable characteristics." The document provides information and test parameters and test nethods for three categories. |

*Test Category A – Basic Utility Properties (required) | *Test Category A – Basic Utility Properties (required) | ||

*Test Category B – Toxicant Assessment (required) | *Test Category B – Toxicant Assessment (required) | ||

*Test Category C – Advanced Analysis and Soil Enhancement Properties | *Test Category C – Advanced Analysis and Soil Enhancement Properties | ||

| − | The IBI document also provides information on sampling procedures, laboratory standards, timing and frequency of testing, feedstcok and production parameters, frequency of testing, reporting, and additional information for specific types of biochar. The document also | + | The IBI document also provides information on sampling procedures, laboratory standards, timing and frequency of testing, feedstcok and production parameters, frequency of testing, reporting, and additional information for specific types of biochar. The document also provides a discussion of H:C ratios, which are used to indicate the stability of a particular biochar. |

==Effects of aging== | ==Effects of aging== | ||

| Line 307: | Line 310: | ||

Below is a summary of some research findings. | Below is a summary of some research findings. | ||

| − | *[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Mia et al.] (2019) observed an increase in carboxylic and phenolic groups, a reduction of oxonium groups and the transformation of pyridine to pyridone with oxidation. This led to increased adsorption of ammonium and reduced adsorption of phosphate. Addition of biochar derived organic matter improved phosphate retention. | + | *[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Mia et al.] (2017; 2019) observed an increase in carboxylic and phenolic groups, a reduction of oxonium groups and the transformation of pyridine to pyridone with oxidation. This led to increased adsorption of ammonium and reduced adsorption of phosphate. Addition of biochar derived organic matter improved phosphate retention. |

*[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Paetsch et al.] (2018) studied effects of fresh and aged biochar on water availability and microbial parameters of a grassland soil. They observed improved water retention and microbial function with aged biochar. This was attributed to increased soil mineralization in soils with aged biochar. | *[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Paetsch et al.] (2018) studied effects of fresh and aged biochar on water availability and microbial parameters of a grassland soil. They observed improved water retention and microbial function with aged biochar. This was attributed to increased soil mineralization in soils with aged biochar. | ||

*[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Paetsch et al.] (2018) observed increased C:N ratios as biochar aged. | *[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Paetsch et al.] (2018) observed increased C:N ratios as biochar aged. | ||

| Line 313: | Line 316: | ||

*[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Quan et al]. (2020) and Spokas (2013) observed biologically-mediated changes in aged biochar. Mineralization resulted in decreased carbon content in aged biochar. | *[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Quan et al]. (2020) and Spokas (2013) observed biologically-mediated changes in aged biochar. Mineralization resulted in decreased carbon content in aged biochar. | ||

*[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Hale et al.] (2012) determined that aged biochar retained its ability to adsorb PAHs. | *[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Hale et al.] (2012) determined that aged biochar retained its ability to adsorb PAHs. | ||

| − | *[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Cao et al.] found that aged biochar had decreased carbon and nitrogen contents; reduced pH values, reduced porosity and specific surface area, and increased oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface. In general, the surface characteristics of the aged biochar varied with soil type. | + | *[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Biochar_and_applications_of_biochar_in_stormwater_management#References Cao et al.] (2017) found that aged biochar had decreased carbon and nitrogen contents; reduced pH values, reduced porosity and specific surface area, and increased oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface. In general, the surface characteristics of the aged biochar varied with soil type. |

==Storage, handling, and field application== | ==Storage, handling, and field application== | ||

| − | The following guidelines for field application of biochar are presented by Major (2010). | + | The following guidelines for field application of biochar are presented by [https://www.biochar-international.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/IBI_Biochar_Application.pdf Major] (2010). |

*Biochar dust particles can form explosive mixtures with air in confined spaces, and there is a danger of spontaneous heating and ignition when biochar is tightly packed. This occurs because fresh biochar quickly sorbs oxygen and moisture, and these sorption processes are exothermic, thus potentially leading to high temperature and ignition of the material. | *Biochar dust particles can form explosive mixtures with air in confined spaces, and there is a danger of spontaneous heating and ignition when biochar is tightly packed. This occurs because fresh biochar quickly sorbs oxygen and moisture, and these sorption processes are exothermic, thus potentially leading to high temperature and ignition of the material. | ||

*Volatile compounds present in certain biochar materials may also represent a fire hazard, but the amount of such compounds found in biochar can be managed by managing the pyrolysis temperature and heating rate. Certain chemicals can be added to biochar to decrease its flammability (e.g. boric acid, ferrous sulfate). The best way to prevent fire is to store and transport biochar in an atmosphere which excludes oxygen. Formulated biochar products such as mixtures with composts, manures, or the production of biochar-mineral complexes will potentially yield products which are much less flammable. | *Volatile compounds present in certain biochar materials may also represent a fire hazard, but the amount of such compounds found in biochar can be managed by managing the pyrolysis temperature and heating rate. Certain chemicals can be added to biochar to decrease its flammability (e.g. boric acid, ferrous sulfate). The best way to prevent fire is to store and transport biochar in an atmosphere which excludes oxygen. Formulated biochar products such as mixtures with composts, manures, or the production of biochar-mineral complexes will potentially yield products which are much less flammable. | ||

| Line 333: | Line 336: | ||

==Sustainability== | ==Sustainability== | ||

| − | Because biochar is produced from biomass, including wastes, it is sustainable from an availability or supply standpoint. Sustainable biochar production, however, is less certain based on current economic constraints. Biochar has several potential markets and exploiting these markets is necessary for biochar production to be sustainable. Examples of specific markets include stormwater media, soil health and fertility, and carbon sequestration [ | + | Because biochar is produced from biomass, including wastes, it is sustainable from an availability or supply standpoint. Sustainable biochar production, however, is less certain based on current economic constraints. Biochar has several potential markets and exploiting these markets is necessary for biochar production to be sustainable. Examples of specific markets include stormwater media, soil health and fertility, and carbon sequestration [http://www.biogreen-energy.com/biochar-production/ Biogreen] (accessed December 10, 2019). Sustainable biochar production must also meet certain environmental and economic criteria, includign the following. |

*Biochar systems should be, at a minimum, carbon and energy neutral. | *Biochar systems should be, at a minimum, carbon and energy neutral. | ||

*Biochar systems should prioritize the use of biomass residuals for biochar production. | *Biochar systems should prioritize the use of biomass residuals for biochar production. | ||

| Line 350: | Line 353: | ||

*Brewer, C.E. 2012. [https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3291&context=etd Biochar characterization and engineering]. PhD thesis. Iowa State University. | *Brewer, C.E. 2012. [https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3291&context=etd Biochar characterization and engineering]. PhD thesis. Iowa State University. | ||

*Budai; A. R. Zimmerman; A.L. Cowie; J.B.W. Webber; B.P. Singh; B. Glaser; C. A. Masiello; D. Andersson; F. Shields; J. Lehmann; M. Camps Arbestain; M. Williams; S. Sohi; S. Joseph. 2013. [https://www.biochar-international.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/IBI_Report_Biochar_Stability_Test_Method_Final.pdf Biochar Carbon Stability Test Method: An Assessment of methods to determine biochar carbon stability]. Accessed December 12, 2019. | *Budai; A. R. Zimmerman; A.L. Cowie; J.B.W. Webber; B.P. Singh; B. Glaser; C. A. Masiello; D. Andersson; F. Shields; J. Lehmann; M. Camps Arbestain; M. Williams; S. Sohi; S. Joseph. 2013. [https://www.biochar-international.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/IBI_Report_Biochar_Stability_Test_Method_Final.pdf Biochar Carbon Stability Test Method: An Assessment of methods to determine biochar carbon stability]. Accessed December 12, 2019. | ||

| − | *Cao, T., Wenfu Chen, Tiexin Yang, Tianyi He, Zunqi Liu, Jun Meng. 2017. [https:// | + | *Cao, T., Wenfu Chen, Tiexin Yang, Tianyi He, Zunqi Liu, Jun Meng. 2017. [https://bioresources.cnr.ncsu.edu/resources/surface-characterization-of-aged-biochar-incubated-in-different-types-of-soil/ Surface Characterization of Aged Biochar Incubated in Different Types of Soil]. BioResources. 12:3: 6366-6377 |

*Chan, K. Y. and Xu, Z. 2009. ''Biochar: nutrient properties and their enhancement''. in J. Lehmann and S. Joseph (eds) Biochar for Environmental Management, Earthscan. London, pp 67–84. | *Chan, K. Y. and Xu, Z. 2009. ''Biochar: nutrient properties and their enhancement''. in J. Lehmann and S. Joseph (eds) Biochar for Environmental Management, Earthscan. London, pp 67–84. | ||

*Clough, T. J. and Condron, L. M. 2010. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46217413_Biochar_and_the_Nitrogen_Cycle_Introduction Biochar and the nitrogen cycle: introduction]. Journal of Environmental Quality. 39:1218–1223. | *Clough, T. J. and Condron, L. M. 2010. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46217413_Biochar_and_the_Nitrogen_Cycle_Introduction Biochar and the nitrogen cycle: introduction]. Journal of Environmental Quality. 39:1218–1223. | ||

| Line 358: | Line 361: | ||

*Ding, Y., Yu-Xue Liu, Wei-Xiang Wu, De-Zhi Shi, Min Yang, and Zhe-Ke Zhong. 2010. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225407749_Evaluation_of_Biochar_Effects_on_Nitrogen_Retention_and_Leaching_in_Multi-Layered_Soil_Columns Evaluation of Biochar Effects on Nitrogen Retention and Leaching in Multi-Layered Soil Columns]. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. Volume 213, Issue 1–4, pp 47–55. | *Ding, Y., Yu-Xue Liu, Wei-Xiang Wu, De-Zhi Shi, Min Yang, and Zhe-Ke Zhong. 2010. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225407749_Evaluation_of_Biochar_Effects_on_Nitrogen_Retention_and_Leaching_in_Multi-Layered_Soil_Columns Evaluation of Biochar Effects on Nitrogen Retention and Leaching in Multi-Layered Soil Columns]. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. Volume 213, Issue 1–4, pp 47–55. | ||

*Domingues, R.R., Paulo F. Trugilho, Carlos A. Silva, Isabel Cristina N. A. de Melo, Leoà nidas C. A. Melo, Zuy M. Magriotis, Miguel A. SaÂnchez-Monedero. 2017. [https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/efa3/11cb4ec367d4992fdc5a9be550bf67b20328.pdf?_ga=2.106287296.211059343.1634858948-2126831147.1634323415 Properties of biochar derived from wood and high-nutrient biomasses with the aim of agronomic and environmental benefits]. PLOS ONE12(5):e0176884. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. | *Domingues, R.R., Paulo F. Trugilho, Carlos A. Silva, Isabel Cristina N. A. de Melo, Leoà nidas C. A. Melo, Zuy M. Magriotis, Miguel A. SaÂnchez-Monedero. 2017. [https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/efa3/11cb4ec367d4992fdc5a9be550bf67b20328.pdf?_ga=2.106287296.211059343.1634858948-2126831147.1634323415 Properties of biochar derived from wood and high-nutrient biomasses with the aim of agronomic and environmental benefits]. PLOS ONE12(5):e0176884. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. | ||

| + | *Dong, X., G. Li, Q. Lin. and X. Zhao. 2017. ''Quantity and quality changes of biochar aged for 5 years in soil under field conditions''. Catena. 159:136-143. | ||

*Flesch, F., Pia Berger, Daniel Robles-Vargas , Gustavo Emilio Santos-Medrano, and Roberto Rico-Martínez. 2019. [https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/9/8/1706/htm Characterization and Determination of the Toxicological Risk of Biochar Using Invertebrate Toxicity Tests in the State of Aguascalientes, México]. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1706; doi:10.3390/app9081706. | *Flesch, F., Pia Berger, Daniel Robles-Vargas , Gustavo Emilio Santos-Medrano, and Roberto Rico-Martínez. 2019. [https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/9/8/1706/htm Characterization and Determination of the Toxicological Risk of Biochar Using Invertebrate Toxicity Tests in the State of Aguascalientes, México]. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1706; doi:10.3390/app9081706. | ||

*Gai X, Wang H, Liu J, Zhai L, Liu S, et al. 2014. [https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0113888 Effects of Feedstock and Pyrolysis Temperature on Biochar Adsorption of Ammonium and Nitrate]. PLoS ONE 9(12). 19 pages. doi:10. 1371/journal.pone.0113888. | *Gai X, Wang H, Liu J, Zhai L, Liu S, et al. 2014. [https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0113888 Effects of Feedstock and Pyrolysis Temperature on Biochar Adsorption of Ammonium and Nitrate]. PLoS ONE 9(12). 19 pages. doi:10. 1371/journal.pone.0113888. | ||

| Line 381: | Line 385: | ||

*Major, J. 2010. [https://www.biochar-international.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/IBI_Biochar_Application.pdf Guidelines on Practical Aspects of Biochar Application to Field Soil in Various Soil Management Systems]. | *Major, J. 2010. [https://www.biochar-international.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/IBI_Biochar_Application.pdf Guidelines on Practical Aspects of Biochar Application to Field Soil in Various Soil Management Systems]. | ||

*Mensah, A.K., and Kwame Agyei Frimpong. 2018. [https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b86b/6c94fb6f0e86fe9f9a50fc56ad242d13fae0.pdf?_ga=2.80206420.211059343.1634858948-2126831147.1634323415 Biochar and/or Compost Applications Improve Soil Properties, Growth, and Yield of Maize Grown in Acidic Rainforest and Coastal Savannah Soils in Ghana]. International Journal of Agronomy. Volume 2018, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6837404 | *Mensah, A.K., and Kwame Agyei Frimpong. 2018. [https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b86b/6c94fb6f0e86fe9f9a50fc56ad242d13fae0.pdf?_ga=2.80206420.211059343.1634858948-2126831147.1634323415 Biochar and/or Compost Applications Improve Soil Properties, Growth, and Yield of Maize Grown in Acidic Rainforest and Coastal Savannah Soils in Ghana]. International Journal of Agronomy. Volume 2018, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6837404 | ||

| + | *Mia S, Dijkstra FA, Singh B. 2017. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311943937_Long-Term_Aging_of_Biochar_A_Molecular_Understanding_With_Agricultural_and_Environmental_Implications Long-term aging of biochar: a molecular understanding with agricultural and environmental implications]. Advances in agronomy 141:1-51. 1st ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.agron.2016.10.001. | ||

| + | *Mia, S., B. Singh, and F.A. Dijkstra. 2019. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333430097_Chemically_oxidized_biochar_increases_ammonium_15N_recovery_and_phosphorus_uptake_in_a_grassland Chemically oxidized biochar increases ammonium 15N recovery and phosphorus uptake in a grassland]. Biology and Fertility of Soils 55:577–588. DOI:10.1007/s00374-019-01369-4. | ||

*Mohanty, S.K., Renan Valenca, Alexander W. Berger, Iris K.M. Yu, Xinni Xiong, Trenton M. Saunders, Daniel C.W. Tsang. 2018. ''Plenty of room for carbon on the ground: Potential applications of biochar for stormwater treatment''. Science of the Total Environment, 625: 1644-1658. | *Mohanty, S.K., Renan Valenca, Alexander W. Berger, Iris K.M. Yu, Xinni Xiong, Trenton M. Saunders, Daniel C.W. Tsang. 2018. ''Plenty of room for carbon on the ground: Potential applications of biochar for stormwater treatment''. Science of the Total Environment, 625: 1644-1658. | ||

*Mumme J, Getz J, Prasad M, Lüder U, Kern J, Mašek O, Buss W. 2018. ''Toxicity screening of biochar-mineral composites using germination tests''. Chemosphere. 207:91-100. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.05.042. | *Mumme J, Getz J, Prasad M, Lüder U, Kern J, Mašek O, Buss W. 2018. ''Toxicity screening of biochar-mineral composites using germination tests''. Chemosphere. 207:91-100. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.05.042. | ||

| Line 387: | Line 393: | ||

*Nguyen, N.T. 2015. ''Adsorption Of Phosphorus From Wastewater Onto Biochar: Batch And Fixed-bed Column Studies''. | *Nguyen, N.T. 2015. ''Adsorption Of Phosphorus From Wastewater Onto Biochar: Batch And Fixed-bed Column Studies''. | ||

*Oleszczuk, P., Izabela Jo´sko, Marcin Ku´smierz. 2013. [https://www.academia.edu/22488554/Biochar_properties_regarding_to_contaminants_content_and_ecotoxicological_assessment Biochar properties regarding to contaminants content and ecotoxicological assessment]. Journal of Hazardous Materials 260 (2013) 375– 382. | *Oleszczuk, P., Izabela Jo´sko, Marcin Ku´smierz. 2013. [https://www.academia.edu/22488554/Biochar_properties_regarding_to_contaminants_content_and_ecotoxicological_assessment Biochar properties regarding to contaminants content and ecotoxicological assessment]. Journal of Hazardous Materials 260 (2013) 375– 382. | ||

| + | *Paetsch, L., C.W. Mueller, I. Kögel-Knabner, M. von Lutzow, C. Girardin, and C. Rumpel 2018.[https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324872987_Effect_of_in-situ_aged_and_fresh_biochar_on_soil_hydraulic_conditions_and_microbial_C_use_under_drought_conditions Effect of in-situ aged and fresh biochar on soil hydraulic conditions and microbial C use under drought conditions]. Scientific Reports 8(1):6852. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-25039-x | ||

*Quan G, Fan Q, Zimmerman AR, Sun J, Cui L, Wang H, Gao B, Yan J. 2020. ''Effects of laboratory biotic aging on the characteristics of biochar and its water-soluble organic products''. J Hazard Mater. 2020 Jan 15;382:121071. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121071 | *Quan G, Fan Q, Zimmerman AR, Sun J, Cui L, Wang H, Gao B, Yan J. 2020. ''Effects of laboratory biotic aging on the characteristics of biochar and its water-soluble organic products''. J Hazard Mater. 2020 Jan 15;382:121071. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121071 | ||

*Quilliam, R. S., Marsden, K. A., Gertler, C., Rousk, J., DeLuca, T. H. and Jones, D. L. 2012. ''Nutrient dynamics, microbial growth and weed emergence in biochar amended soil are influenced by time since application and reapplication rate''. Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Environment. 158:192–199. | *Quilliam, R. S., Marsden, K. A., Gertler, C., Rousk, J., DeLuca, T. H. and Jones, D. L. 2012. ''Nutrient dynamics, microbial growth and weed emergence in biochar amended soil are influenced by time since application and reapplication rate''. Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Environment. 158:192–199. | ||

| Line 397: | Line 404: | ||

*Spokas, K.A. 2013. [https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/41695/Reprints/gcbb12005.pdf Impact of biochar field aging on laboratory greenhouse gas production potentials]. GCB Bioenergy (2013) 5, 165–176, doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12005 | *Spokas, K.A. 2013. [https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/41695/Reprints/gcbb12005.pdf Impact of biochar field aging on laboratory greenhouse gas production potentials]. GCB Bioenergy (2013) 5, 165–176, doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12005 | ||

*Ulrich, B.A., Megan Loehnert and Christopher P. Higgins. 2017. ''Improved contaminant removal in vegetated stormwater biofilters amended with biochar'' Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology. 3:726-734. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7EW00070G | *Ulrich, B.A., Megan Loehnert and Christopher P. Higgins. 2017. ''Improved contaminant removal in vegetated stormwater biofilters amended with biochar'' Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology. 3:726-734. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7EW00070G | ||

| + | *Verheijen, F.G.A., A.C. Bastos, HP Schmidt, M. Brandao. 2015. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275770511_Biochar_Sustainability_and_Certification Biochar Sustainability and Certification]. In book: Biochar for Environmental management, Science, Technology and Implementation. 2nd Edition. Chapter 28. Publisher: Routledge. Editors: Johannes Lehmann & Stephen Joseph. | ||

*Wang, K., Na Peng, Guining Lu, Zhi Dang, 2018. ''Effects of Pyrolysis Temperature and Holding Time on Physicochemical Properties of Swine-Manure-Derived Biochar''. Waste and Biomass Valorization. 1-12 DOI: 10.1007/s12649-018-0435-2 | *Wang, K., Na Peng, Guining Lu, Zhi Dang, 2018. ''Effects of Pyrolysis Temperature and Holding Time on Physicochemical Properties of Swine-Manure-Derived Biochar''. Waste and Biomass Valorization. 1-12 DOI: 10.1007/s12649-018-0435-2 | ||

*Yang, F., Yue Zhou, Weiming Liu, Wenzhu Tang, Jun Meng, Wenfu Chen, and Xianzhen Li. 2019. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335044552_Strain-Specific_Effects_of_Biochar_and_Its_Water-Soluble_Compounds_on_Bacterial_Growth Article Strain-Specific Effects of Biochar and Its Water-Soluble Compounds on Bacterial Growth]. Appl. Sci. 9(16), 3209; https://doi.org/10.3390/app9163209. | *Yang, F., Yue Zhou, Weiming Liu, Wenzhu Tang, Jun Meng, Wenfu Chen, and Xianzhen Li. 2019. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335044552_Strain-Specific_Effects_of_Biochar_and_Its_Water-Soluble_Compounds_on_Bacterial_Growth Article Strain-Specific Effects of Biochar and Its Water-Soluble Compounds on Bacterial Growth]. Appl. Sci. 9(16), 3209; https://doi.org/10.3390/app9163209. | ||

*Yao, Y., Bin Gao, Mandu Inyang, Andrew R. Zimmerman, Xinde Cao, Pratap Pullammanappallil, Liuyan Yang. 2011 ''Biochar derived from anaerobically digested sugar beet tailings:Characterization and phosphate removal potential''. Bioresource Technology. 102:6273-6278 | *Yao, Y., Bin Gao, Mandu Inyang, Andrew R. Zimmerman, Xinde Cao, Pratap Pullammanappallil, Liuyan Yang. 2011 ''Biochar derived from anaerobically digested sugar beet tailings:Characterization and phosphate removal potential''. Bioresource Technology. 102:6273-6278 | ||

*Yaoa, Y., Bin Gaoa, Mandu Inyanga, Andrew R. Zimmermanb, Xinde Caoc, Pratap Pullammanappallila, Liuyan Yangd. 2011. [https://people.clas.ufl.edu/azimmer/files/Publication-pdf/Yao11_Removal-of-phosphate-from-aqueous-solution-by-biochar-derived-from.pdf Removal of phosphate from aqueous solution by biochar derived from anaerobically digested sugar beet tailings]. Journal of Hazardous Materials 190:501–507 | *Yaoa, Y., Bin Gaoa, Mandu Inyanga, Andrew R. Zimmermanb, Xinde Caoc, Pratap Pullammanappallila, Liuyan Yangd. 2011. [https://people.clas.ufl.edu/azimmer/files/Publication-pdf/Yao11_Removal-of-phosphate-from-aqueous-solution-by-biochar-derived-from.pdf Removal of phosphate from aqueous solution by biochar derived from anaerobically digested sugar beet tailings]. Journal of Hazardous Materials 190:501–507 | ||

| − | *Yoo, G. and Kang, H. 2010. | + | *Yoo, G. and Kang, H. 2010. Effects of biochar addition on greenhouse gas emissions and microbial responses in a short-term laboratory experiment. Journal of Environmental Quality. 41:1193–1202. |

*Yuan-Ying Wang, Xiang-Rong Jing, Ling-Li Li, Wu-Jun Liu, Zhong-Hua Tong, Hong Jiang. 2017. ''Biotoxicity Evaluations of Three Typical Biochars Using a Simulated System of Fast Pyrolytic Biochar Extracts on Organisms of Three Kingdoms''. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 1, 481-488. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b01859 | *Yuan-Ying Wang, Xiang-Rong Jing, Ling-Li Li, Wu-Jun Liu, Zhong-Hua Tong, Hong Jiang. 2017. ''Biotoxicity Evaluations of Three Typical Biochars Using a Simulated System of Fast Pyrolytic Biochar Extracts on Organisms of Three Kingdoms''. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 1, 481-488. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b01859 | ||

*Zhang, M., Muhammad Riaz, Lin Zhang, Zeinab El-desouki, and Cuncang Jiang. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333737870_Biochar_Induces_Changes_to_Basic_Soil_Properties_and_Bacterial_Communities_of_Different_Soils_to_Varying_Degrees_at_25_mm_Rainfall_More_Effective_on_Acidic_SoilsImage_1TIFImage_2TIFImage_3TIFImage_4TI Biochar Induces Changes to Basic Soil Properties and Bacterial Communities of Different Soils to Varying Degrees at 25 mm Rainfall: More Effective on Acidic Soils]. 2019. Frontiers Microbio. 12:10:1321. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01321 | *Zhang, M., Muhammad Riaz, Lin Zhang, Zeinab El-desouki, and Cuncang Jiang. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333737870_Biochar_Induces_Changes_to_Basic_Soil_Properties_and_Bacterial_Communities_of_Different_Soils_to_Varying_Degrees_at_25_mm_Rainfall_More_Effective_on_Acidic_SoilsImage_1TIFImage_2TIFImage_3TIFImage_4TI Biochar Induces Changes to Basic Soil Properties and Bacterial Communities of Different Soils to Varying Degrees at 25 mm Rainfall: More Effective on Acidic Soils]. 2019. Frontiers Microbio. 12:10:1321. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01321 | ||

| Line 410: | Line 418: | ||

<noinclude> | <noinclude> | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Level 2 - Technical and specific topic information/soils and media]] |

</noinclude> | </noinclude> | ||

Latest revision as of 15:45, 29 August 2023

Biochar is a charcoal-like substance that’s made by burning organic material such as crop residues; yard, food and forestry wastes; and animal manures. Beneficial properties of biochar include the following.

Regarding water quality, additional research is needed, but generally:

Biochar is also found to be beneficial for composting. |

This page provides information on biochar. While providing extensive information on biochar, there is a section focused specifically on stormwater applications for biochar.

Link to a table comparing properties of different organic materials

Contents

- 1 Overview and description

- 2 Applications for biochar in stormwater management

- 3 Effects of feedstock and production temperature

- 4 Properties of biochar

- 5 Effects of biochar on physical and chemical properties of soil and bioretention media

- 6 Standards, classification, testing, and distributors

- 7 Effects of aging

- 8 Storage, handling, and field application

- 9 Sustainability

- 10 References

Overview and description

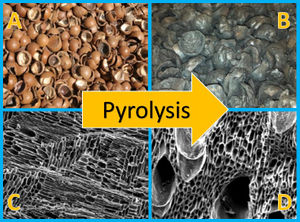

Biochar is a charcoal-like substance that’s made by burning organic material from biomass. The two most common proceesses for producing biochar are pyrolysis and gasification. During pyrolysis, the organic material is heated to 250-800oC in a limited oxygen environment. Gasification involves temperatures greater than 700oC in the presence of oxygen.

Biomass waste materials appropriate for biochar production include crop residues (both field residues and processing residues such as nut shells, fruit pits, bagasse, etc); yard, food and forestry wastes; and animal manures. Clean feedstocks with 10 to 20 percent moisture and high lignin content are recommended. Examples are field residues and woody biomass. Using contaminated feedstocks, including feedstocks from railway embankments or contaminated land, can introduce toxins into the soil, drastically increase soil pH and/or inhibit plants from absorbing minerals. The most common contaminants are heavy metals—including cadmium, copper, chromium, lead, zinc, mercury, nickel and arsenic, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

Biochar is black, highly porous, lightweight, fine-grained and has a large surface area. Approximately 70 percent of its composition is carbon. The remaining percentage consists of nitrogen, hydrogen and oxygen among other elements. Biochar’s chemical composition varies depending on the feedstocks used to make it and methods used to heat it.

Biochar benefits for soil may include but are not limited to

- enhancing soil structure and soil aggregation;

- increasing water retention;

- decreasing acidity;

- reducing nitrous oxide emissions;

- improving porosity;

- regulating nitrogen leaching;

- improving electrical conductivity; and

- improving microbial properties.

Biochar is also found to be beneficial for composting, since it reduces greenhouse gas emissions and prevents the loss of nutrients in the compost material. It also promotes microbial activity, which in turn accelerates the composting process. Plus, it helps reduce the compost’s ammonia losses, bulk density and odor (Spears, 2018; Hoffman-Krull, 2019).

Applications for biochar in stormwater management

Biochar has several potential applications for stormwater management.

- Biochar increases water holding capacity of soil, improves aggregation in fine-textured soils, increases saturated hydraulic conductivity (k) in fine- and medium-textured soils, and decreases hydraulic conductivity in very coarse-textured soils.

- Improves the fertility of nutrient-poor soils. In nutrient-poor soils, biochar appears to consistently improve nutrient cycling and availability for plants. Results for other soils are mixed and depend on the biochar and soil characteristics.

- Biochar generally improves retention of metals and PAHs.

- Results for bacteria and pathogens are mixed, but some studies indicate increased retention, primarily associated with straining resulting from increased surface area and micropore structure in biochar-amended soils.

- Biochar is likely to have limited effects on phosphorus retention unless specifically amended to retain phosphorus.

Possible implications for stormwater management include the following.

- Engineered media. Biochar incorporated into engineered media can increase water retention and infiltration. Low-nutrient biochars (e.g. wood-based versus manure- or sludge-based) produced at relatively low temperatures (less than 600oC) can improve phosphorus retention. Biochar may enhance nutrient cycling and improve fertility in media with relatively low nutrient concentrations (e.g. media mixes having lower fractions of compost).

- Contaminant hotspots. Biochar can be incorporated into treatment practices in areas with high or potentially high concentrations of metals and organic pollutants.

- Turf amendment/soil compaction. Biochar can be added to turf or compacted media to improve hydraulic performance and nutrient cycling.

- Filtration practices. Biochar can be used alone or mixed with other components for stormwater filtration applications, including but not limited to the following:

- filtration media in new treatment systems, especially roof downspout units and aboveground vaults;

- Supplemental or replacement media in existing treatment systems such as sand filters;

- Direct media addition to a stormwater storage vault ;

- Direct application in bioretention or swale systems;

- Filtration socks and slings;

- Hanging filters in catch basins.

- Underground infiltration basins and trenches. Many underground infiltration practices are constructed in very coarse textured soils that may have limited ability to retain pollutants. Biochar can reduce infiltration rates and adsorb pollutants in these systems.

- Climate-related effects. While not specifically a stormwater objective, biochar incorporated into stormwater practices can sequester carbon and reduce nitrous oxide emissions.

Potential biochar stormwater applications (adapted from Table 6 in Mohanty et al. (2018)).

Link to this table

| Practice | Potential benefits of biochar |

|---|---|

| Downspout filter boxes |

|

| Tree boxes |

|

| Green roofs |

|

| Biofiltration |

|

| Constructed ponds and wetlands |

|

| Sand filters |

|

| Level spreader/filter strips |

|

| Swales |

|

| Infiltration trench/basin |

|

Recommended reading

- Emerging Best Management Practices in Stormwater: Biochar as Filtration Media - Pacific Northwest Pollution Prevention Resource Center

- Improving Stormwater Control Measure Performance with Biochar - Deeproot

- Reducing Stormwater Runoff and Pollutant Loading with Biochar Addition to Highway Greenways - Final Report for NCHRP IDEA Project 182

- Mohanty et al. (2018)

Effects of feedstock and production temperature

Although the basic structure of all biochars is similar, the physical-chemical properties of biochar varies with the source material and with the temperature used in production.

Effect of feedstock (source material)

Since a wide variety of organic material can be used to produce biochar, it is not feasible to discuss each material separately. We provide the following general conclusions. Literature used to develop these conclusions is provided at the end of this section.

- Compared to wood derived biochar, non-wood feedstock such as grass, sludge, and manure yields biochar with fewer aromatic but more aliphatic groups and higher ash content. Greater concentrations of aliphatic compounds are associated with more reactive biochar.

- Manure- and sludge-based biochar contains higher concentration of nutrients than wood-based biochar and are therefore more likely to be a source of nutrient leaching.

- Manure- and sludge-based biochar attenuate metals more than wood based biochars

- Biochar parameters most affected by feedstock properties are total organic carbon, fixed carbon, and mineral elements of biochar. Feedstocks such as sawdust, wheat straw, and peanut shell have higher carbon concentrations than feedstocks such as manure, sludges, and waste paper.

- Capacity for carbon sequestration is primarily affected by feedstock, with higher carbon compounds having greater sequestration capacity.

- High ash biochars, such as manures and coffee husk, exhibit higher cation exchange capacity, which may increase nutrient capture, although high initial nutrient concentrations may offset this and even contribute to nutrient loss.

The International Biochar Initiative (see Appendix 6) provides a classification system for biochar feedstocks, shown below.

- Unprocessed Feedstock Types

- Rice hulls & straw

- Maize cobs & stover

- Non-maize cereal straws

- Sugar cane bagasse & trash

- Switch grass, Miscanthus & bamboo

- Oil crop residues e.g., sugar beet, rapeseed

- Leguminous crop residues e.g., soy, clover

- Hemp residues

- Softwoods (coniferous)

- Hardwoods (broadleaf)

- Processed Feedstock Types

- Cattle manure

- Pig manure

- Poultry litter

- Sheep manure

- Horse manure

- Paper mill sludge

- Sewage sludge

- Distillers grain

- Anaerobic digester sludge

- Biomass fraction of MSW – woody material

- Biomass fraction of MSW – yard trimmings

- Biomass fraction of MSW – food waste

- Food industry waste

Literature

- Zhaoa et al. (2013) examined cow manure, pig manure, shrimp hull, bone dregs, wastewater sludge, waste paper, sawdust, grass, wheat straw, peanut shell, Chlorella, and water weeds

- Domingues et al., (2017) examined wood-based biochars (eucalyptus sawdust, pine bark), sugarcane bagasse, chicken manure, and coffee husk

- Jindo et al. (2014) examined rice husk, rice straw, apple tree wood chips, and oak tree wood chips

- Mohanty et al. (2018) provide an extensive discussion and literature review of different feedstocks and associated biochar properties

- Gai et al. (2014) studied twelve biochars produced from wheat straw, corn straw, and peanut shell

- International Biochar Initiative provide a general discussion of feedstocks

- Conz et al. (2017) studied poultry litter, sugarcane straw, rice hull and sawdust

- Jahromi and Fulcher studied biosolids and green waste, corn straw and rice straw, gasifed rice hulls, hardwood, pelleted agricultural or forestry residues, switchgrass, and timber harvest residues

- Zhao et al. (2017) studied sewage sludge, agriculture biomass waste, and wood biomass waste

Effect of production temperature

Changes in the properties of biochar result from loss of volatile organic matter as temperature increases. This leads to a gradual loss in the number of functional groups on the biochar and increased aromaticity as temperature increases.

In general, the following conclusions are applicable for biochar used in stormwater applications.

- If retention of nutrients and most pollutants is desired, biochars produced at temperatures less than 600oC should be selected

- If the goal is to improve soil physical or hydraulic properties biochars produced at temperatures greater than 600oC should be selected

The following information comes from a literature review of the effects of production temperature on biochar

- Biochar yield and contents of N, hydrogen and oxygen decrease as pyrolysis temperature increases from 400˚C to 700˚C

- pH and contents of ash and carbon increase with greater pyrolysis temperature

- Particle size and porosity increase with greater pyrolysis temperature

- Hydrophobicity increases with greater pyrolysis temperature

- Mohanty et al., (2018)

- Zhaoa et al. (2013)

- Domingues et al., (2017)

- Klasson, (2017)

- Zhao et al., (2017)

- Jindo et al. (2014)

- Wang et al., (2018)

- Lyu et al. (2016)

- Gai et al. (2014)

- Conz et al. (2017)

Properties of biochar

This section includes a discussion of chemical and physical properties of biochar, and potential contaminants in biochar.

Chemical-physical properties of biochar

The properties of biochar vary depending on the feedstock and production temperature, as discussed above. Consequently there is considerable variability in the chemical and physical properties of different biochars. The table below summarizes data from our literature review. Some conclusions from the literature are summarized below.

- Biochar has a large surface area.

- Cation exchange capacity (CEC) decreases as pyrolysis temperature increases. This is due to the loss of volatile organic content and associated functional groups as temperature increases. As CEC decreases, the ability of biochar to retain negatively charged chemicals, such as phosphate, decreases.

- Non-wood vegetative feedstocks have a greater CEC than wood feedstocks. This is due to a greater percentage of aliphatic compounds and associated functional groups. Non-wood feedstocks primarily consist of grasses.

- Sludges and manure-based biochars have high nutrient content and are thus not satisfactory for managing stormwater.

Chemical and physical properties of biochar.

Link to this table

| Property | Range found in literature1 | Median value from literature |

|---|---|---|

| Total phosphorus (%) | 0.0061 - 1.086 | 0.0618 |

| Total nitrogen (%) | 1.2 - 2.4 | 0.88 |

| Total potassium (%) | 0.0079 - 1.367 | 0.181 |

| Total carbon (%) | 24.2 - 90.9 | 66 |

| Total hydrogen (%) | 0.67 - 4.3 | 2.8 |

| Total oxygen (%) | 2.69 - 28.7 | 16.3 |

| pH | 6.43 - 10.4 | 9.66 |

| Cation exchange capacity (cmol/kg) | 0.1 - 562 | 43.1 |

| Surface area (m2/g | 2.78 - 203 | 30.6 |

| Electrical conductivity (μs/cm) | 100 - 2221 | 231.5 |

| Pore volume (cm3/g) | 0.006 - 0.51 | 0.036 |

| Total calcium (%) | 0.0954 - 3.182 | 0.590 |

| Total magnesium (%) | 0.0297 - 0.2801 | 0.0587 |

| Total copper (%) | 0.0001 - 0.0078 | 0.00025 |

| Total zinc (%) | 0.0002 - 0.0152 | 0.00135 |

| Total aluminum (%) | 0.001 - 0.1929 | 0.0290 |

| Total iron (%) | 0.0009 - 0.2209 | 0.0333 |

| Total manganese (%) | 0.0001 - 0.1025 | 0.00145 |

| Total sulfur (%) | 0.01 - 0.44 | 0.05 |

Primary references for this data:

|

Potential contaminants in biochar

Potential contaminants associated with biochar are a function of the source material and production temperature. Of greatest concern are metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Oleszcuk et al. (2013) examined metal and PAH concentrations in four biochars (elephant grass, coconut shell, wicker, and wheat straw). Metal concentrations (mg/kg) in the biochars are summarized below. Tier 1 Soil Reference Values (SRVs) are included in parentheses (Tier 1 values correspond with no restrictions on use of the soil).

- Cadmium: 0.04-0.87 (25)

- Copper: nd-3.81 (100)

- Nickel: nd-9.95 (560)

- Lead: 20.6-23.7 (300)

- Zinc: 30.2-102.0 (8700)

- Chromium (Cr): nd-18.0 (44,000 for CrIII; 87 for CrVI)

Concentrations in biochar are well below Tier 1 SRVs.

In the study by Oleszcuk et al. (2013), total PAHs ranged from 1,124.2 ng/g to 28,339.1 ng/g (ppb). The dominant group of PAHs were 3-ring compounds which comprised 64.6% to 82.6% of total PAHs content. The primary compounds included, in order of abundance, phenanthrene, fluorene, anthracene, and pyrene. No 6-ring PAHs were observed. Concentrations of PAHs and other organic contaminants, such as dioxins, decreases with increasing pyrolysis temperature (Lyu et al., 2016).

In general, biochars mixed with soil do not inhibit germination or root growth. Biochar may enhance soil fertility by providing nutrients or more commonly by slowing the release of nutrients from materials such as compost. Toxic effects have been observed for some invertebrates, indicating that in sensitive environments, biochar testing is advisable (Oleszcuk et al., 2013; Mumme et al., 2018; Flesch et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2017) .

Effects of biochar on physical and chemical properties of soil and bioretention media

In this section we provide information on effects of biochar on pollutant attenuation and the physical properties of soil and bioretention media.

Effect of biochar on retention and fate of phosphorus

| Biochar is not likely to provide significant phosphorus retention in bioretention practices unless impregnated with cations (e.g. magnesium) during production at relatively low temperatures (e.g. less than 600oC.) |

Biochar may have several properties for managing stormwater, such as increased water and pollutant retention, improving soil physical properties, and attenuating bacteria and pathogens. Biochar has been examined as a potential amendment to engineered media in bioretention or other stormwater control practices. With respect to phosphorus, information from the literature is mixed. Below are summaries from several studies.

- Erickson et al. observed phosphorus release from media that included 15% biochar and 20% leaf compost. This research is continuing and initial results suggest phosphorus release also occurs with 10% compost.

- Mohanty et al. (2018) observed that biochar does not absorb phosphate efficiently. Phosphorus retention can be enhanced by impregnating biochar with cations such as magnesium and zinc.

- Reddy et al. (2014) found that biochar reduced influent phosphate concentrations by 47% in column experiments. Influent concentrations were 0.57 and 0.82 mg/L for unwashed and washed biochar, respectively. These concentrations are on the high end of concentrations found in urban stormwater.

- Yaoa et al. (2011) observed retention in biochar-(sugar beet source)amended soils that were fertilized. Adsorption was dominated by magnesium oxides and maximum adsorption occurred at pH values less than 4.

- Zhaoa et al. (2013) studied different feedstocks and observed high phosphorus concentrations in animal-based feedstocks and wastewater sludge (0.065 - 0.44%) compared to other feedstocks (0.007 - 0.07%)

- Iqbal et al. (2015) examined leaching of phosphorus from compost (80% yard and 20% food waste) and co-composted biochar (100% fir-forest slash). They found biochar amendments did not significantly reduce the leaching of phosphorus compared to the compost only treatment. Phosphorus leached from biochar, but because phosphorus concentrations in biochar are low, this leaching contributed little total phosphorus. Leached phosphorus was primarily in the form of orthphosphate.

- Han et al. (2018) found that addition of biochar to soil led to increased desorption of phosphorus during winter freeze-thaw cycles.

- Soinne et al. (2014) observed no effect of biochar on phosphorus retention in a sandy and two clay soils.

Effect of biochar on retention and fate of other pollutants

- Nitrogen. Biochar effects on nitrogen retention depend on the properties of the biochar and stormwater runoff. Biochars produced at relatively low temperatures (less than 600oC) provide some retention of organic nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen in stormwater runoff. Mechanisms for nitrogen retention include adsorption of ammounium and nitrogen immobilization. Leaching of nitrogen may decrease due to increased water holding capacity (Iqbal et al., 2015; Gai et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2013; Ding et al., 2010).

- Metals. Biochar enhances retention of metals in stormwater runoff. (Reddy et al., 2014; Domingues et al., 2017; Iqbal et al., 2015)

- Organics. Biochar significantly retains polynuclear aromatic hydrocrabons in stormwater runoff (Reddy et al., 2014; Domingues et al., 2017; Ulrich et al., 2017; Iqbal et al., 2015)

- Bacteria and viruses. Biochar effects on bacteria and virus retention are a function of the particle size of the biochar. Fine-grained biochars enhance removal of bacteria in stormwater runoff through straining of microorganisms (Reddy et al., 2014; Sasidharan et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2019).

- Dissolved organic carbon. Biochar shows limited retention of dissolved carbon in stormwater runoff (Iqbal et al., 2015).

- Greenhouse gas emissions. Biochar effectively sequesters carbon and reduces loss of greenhouse gases when incorporated into soil or media, particularly soil with high organic matter content (Zhaoa et al., 2013; Mohanty et al., 2018; 37. Agyarko-Mintah et al., 2017).

Effect of biochar on soil physical and hydraulic properties

Because of a large surface area and internal porosity, biochar can affect soil physical properties (Mohanty et al., 2018; Herrera Environmental Consultants, 2015; Iqbal et al., 2015; Imhoff, 2019; Jien and Wang, 2013). These effects are most pronounced in soils with low organic matter concentration.

- Porosity and surface area. Biochar significantly increases the porosity of most soils.

- Water holding capcity. Biochar significantly increases the water holding capacity of soil.

- Hydraulic conductivity. Biochar increases the hydraulic conductivity of fine- and medium-grained soils and may decrease the hydraulic conductivity of coarse-grained soils.

- Structure. Biochar enhances aggregation in soils, thus enhancing soil structure and potentially increasing soil macroporosity.

Effects of biochar on soil fertility, plant growth, and microbial function

| Effects of biochar on soil fertility, plant growth, and microbial function are affected by several factors, including feedstock, production method, soil, application rate, and biochar age. Biochar has few negative effects on fertility, plant growth and microbial function and in many cases has the potential to greatly improve soil physical, chemical and biological conditions. |

DeLuca et al. (2015) provide an extensive discussion of biochar effects on nutrient cycling, fertility, and microbial function in soil. Their paper is based on an extensive review of the literature at the time of their publication. The following discussion is primarily based on information contained in this document. A list of suggested articles is provided at the end of this section.

Biochars derived from nutrient rich sources such as manure and sludge may directly provide nutrients. Most biochars, however, have limited direct contribution to the nutrient pool with the exception of potassium and ammonium. Biochar may accelerate nutrient cycling over long time scales by serving as a short-term source of highly available nutrients, which become incorporated into living biomass and labile soil organic pools. Thus biochar, while typically providing modest inputs of nutrients, enhances the bioavailability of nutrients in soil.

Because biochar typically enhances soil physical properties, including increasing water holding capacity, improving gas exchange, increasing surface area and availability of microsites for microbes, and in some cases increasing cation exchange capacity, biochar enhances microbial activity in soil. In addition, carbon in biochar provides a sorptive surface that can retain nutrients and thus minimize leaching and volatilization of nutrients.

Several studies suggest biochar amendments in soil result in increased microbial biomass, while other studies show no effect. Mixed results have also been observed for the effects of biochar on microbial community composition.

Specific conclusions from the DeLuca et al. (2015) paper include the following.

- Biochar increases nitrogen mineralization is soils with low mineralization potential (e.g. forest soils). Wood-based biochars appear to have the greatest effect on mineralization.

- Aged biochar shows greater accumulation of inorganic nitrogen, suggesting reduced nitrogen availability and cycling over time. Additions of fresh biochar are recommended if continued enhanced nutrient cycling is desired.

- Low-temperature biochars have greater nitrogen immobilization due to more bioavailable carbon, but immobilization to these biochars is likely to be short-term.

- Biochar effects on nitrogen fixation are mixed, but studies of compost-biochar mixes show a decrease in nitrogen fixation while wood-based biochars show increased fixation.

- Phosphorus in wood-based biochars is largely immediately soluble and readily released to soil, where it becomes available to plants. However, the overall phosphorus concentration in wood-based biochars is much lower than in manure- or sludge-based biochars.

- Application of biochar at varying rates result in an increase in available soil phosphorus, but there is little evidence this translates into increased plant uptake. This may be due to presence of abundant sites for adsorption in fresh biochars. Phosphorus decreases over time as biochar ages.

- Laboratory studies have shown that biochar addition induces an increase in phosphatase activity which would increase the release of P from soil organic matter and organic residues.

- Biochar effects on phosphorus are likely to be greatest in acidic soils, where addition of biochar raises pH and increases the potential adsorption to alkaline metals (calcium, potassium, magnesium).

- Biochar effects on sulfur are uncertain, but are likely to be similar to those for phosphorus. Any enhanced adsorption or mobilization, particularly in aged biochar, will most likely be attributable to enhanced water holding capacity and surface area.

Recommended reading

- Anderson, C. R., Condron, L. M., Clough, T. J., Fiers, M., Stewart, A., Hill, R. A. and Sherlock, R. R. 2011. Biochar induced soil microbial community change: Implications for biogeochemical cycling of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus. Pedobiologia, vol 54, pp309–320.

- Borchard, N., Wolf, A., Laabs, V., Aeckersberg, R., Scherer, H. W., Moeller, A. and Amelung, W. 2012. Physical activation of biochar and its meaning for soil fertility and nutrient leaching – a greenhouse experiment. Soil Use and Management. 28:177–184.

- Chan, K. Y. and Xu, Z. 2009. Biochar: nutrient properties and their enhancement. in J. Lehmann and S. Joseph (eds) Biochar for Environmental Management, Earthscan. London, pp 67–84.

- Clough, T. J. and Condron, L. M. 2010. Biochar and the nitrogen cycle: introduction. Journal of Environmental Quality. 39:1218–1223.

- Crutchfield, E. F., Merhaut, D. J., Mcgiffen, M. E. and Allen, E. B. 2010. Effects of biochar on nutrient leaching and plant growth. Hortscience, vol 45, S163–S163.

- Jeffery, S., Verheijen, F. G. A., Van Der Velde, M. and Bastos, A. C. 2011. A quantitative review of the effects of biochar application to soils on crop productivity using meta-analysis. Agriculture Ecosystems and Environment. 144:175–187.

- Jones, D. L., Rousk, J., Edwards-Jones, G., DeLuca, T. H. and Murphy, D. V. 2012. Biochar-mediated changes in soil quality and plant growth in a three year field trial. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 45:113–124.

- Joseph, S. D., Downie, A., Munroe, P., Crosky, A. and Lehmann, J. 2007. Biochar for carbon sequesteration, reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and enhancement of soil fertility; a review of the materials science. Proceedings from Australian Combustion Symposium. University of Sydney, Australia. pp1–4.

- Laird, D., Pierce Flemming, Baiqun Wang, Robert Horton, Douglas Karlen. 2010. Biochar impact on nutrient leaching from a Midwestern agricultural soil. Agronomy Publications. Iowa State University. 9 p.

- Lehmann, J., Rillig, M. C., Thies, J., Masiello, C. A., Hockaday, W. C. and Crowley, D. 2011. Biochar effects of soil biota – A review. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 43:1812–1836.

- Nelson, N. O., Agudelo, S. C., Yuan, W. and Gan, J. 2011. Nitrogen and phosphorus availability in biochar-amended soils. Soil Science. 176:218–226.

- Pietikäinen, J., Kiikkila, O. and Fritze, H. 2000. Charcoal as a habitat for microbes and its effect on the microbial community of the underlying humus. Oikos. 89:231–242.

- Quilliam, R. S., Marsden, K. A., Gertler, C., Rousk, J., DeLuca, T. H. and Jones, D. L. 2012. Nutrient dynamics, microbial growth and weed emergence in biochar amended soil are influenced by time since application and reapplication rate. Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Environment. 158:192–199.

- Schultz, H. and Glaser, B. 2012. Effects of biochar compared to organic and inorganic fertilizers on soil quality and plant growth in a greenhouse experiment. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 175:410–422.

- Yoo, G. and Kang, H. 2010. Effects of biochar addition on greenhouse gas emissions and microbial responses in a short-term laboratory experiment. Journal of Environmental Quality. 41:1193–1202.

Standards, classification, testing, and distributors

Because of the large number of potential feedstocks, production conditions (primarily temperature), and applications for biochar, biochar classification is an active area of research. The information in this section largely comes from the International Biochar Initiative, but some additional references include the following.

- Arbestain et al. (2015): A biochar classification system and associated test methods

- Klassen (2017): Biochar characterization and a method for estimating biochar quality from proximate analysis results

- Leng et al. (2019): Biochar stability assessment methods: A review

- United States Biochar Initiative

- Budai et al. (2013): Biochar Carbon Stability Test Method: An Assessment of methods to determine biochar carbon stability

Biochar standards

The Internation Biochar Initiative (IBI) developed Standardized Product Definition and Product Testing Guidelines for Biochar That Is Used in Soil, also referred to The Biochar Standards. These standards provide guidelines and is not a formal set of industry specifications. The goal of The Biochar Standards is to "universally and consistently define what biochar is, and to confirm that a product intended for sale or use as biochar possesses the necessary characteristics for safe use. The IBI Biochar Standards also provide common reporting requirements for biochar that will aid researchers in their ongoing efforts to link specific functions of biochar to its beneficial soil and crop impacts." The IBI also provides a certification program. Information on the standards and certification are found on International Biochar Institute's website or at the IBI's Standardized Product Definition and Product Testing Guidelines for Biochar That Is Used in Soil.

The IBI also provides a biochar classification tool. Currently, four biochar properties are classified:

- Carbon storage value

- Fertilizer value (P, K, S, and Mg only)

- Liming value

- Particle size distribution

Distributors

A list of biochar distributors is provided on the United States Biochar Initiative website (USBI). Note the USBI neither provides endorsements nor accepts liability for any particular product or technology listed.

Test methods

There is no universally accepted standard for biochar testing. The International Biochar Initiative (IBI) developed Standardized Product Definition and Product Testing Guidelines for Biochar That Is Used in Soil. The goals of this document are to provide "stakeholders and 5 commercial entities with standards to identify certain qualities and characteristics of biochar materials according to relevant, reliable, and measurable characteristics." The document provides information and test parameters and test nethods for three categories.

- Test Category A – Basic Utility Properties (required)

- Test Category B – Toxicant Assessment (required)

- Test Category C – Advanced Analysis and Soil Enhancement Properties

The IBI document also provides information on sampling procedures, laboratory standards, timing and frequency of testing, feedstcok and production parameters, frequency of testing, reporting, and additional information for specific types of biochar. The document also provides a discussion of H:C ratios, which are used to indicate the stability of a particular biochar.

Effects of aging

Biochar undergoes transformations in soil after application, primarily through oxidation processes, typically mediated by microbes. Several researchers have studied effects of aging on biochar properties. Although researchers observe similar changes in the chemical and physical structure of biochar with aging, observed effects vary. It is therefore difficult to draw general conclusions about likely changes in the effects of biochar aging on fate of pollutants and soil hydraulic properties.

Below is a summary of some research findings.

- Mia et al. (2017; 2019) observed an increase in carboxylic and phenolic groups, a reduction of oxonium groups and the transformation of pyridine to pyridone with oxidation. This led to increased adsorption of ammonium and reduced adsorption of phosphate. Addition of biochar derived organic matter improved phosphate retention.

- Paetsch et al. (2018) studied effects of fresh and aged biochar on water availability and microbial parameters of a grassland soil. They observed improved water retention and microbial function with aged biochar. This was attributed to increased soil mineralization in soils with aged biochar.

- Paetsch et al. (2018) observed increased C:N ratios as biochar aged.

- Dong et al. (2017) observed increased specific surface area, increased carbon content, smaller average pore size, but no change in chemical structure of aged biochar versus fresh biochar.

- Quan et al. (2020) and Spokas (2013) observed biologically-mediated changes in aged biochar. Mineralization resulted in decreased carbon content in aged biochar.

- Hale et al. (2012) determined that aged biochar retained its ability to adsorb PAHs.

- Cao et al. (2017) found that aged biochar had decreased carbon and nitrogen contents; reduced pH values, reduced porosity and specific surface area, and increased oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface. In general, the surface characteristics of the aged biochar varied with soil type.

Storage, handling, and field application

The following guidelines for field application of biochar are presented by Major (2010).

- Biochar dust particles can form explosive mixtures with air in confined spaces, and there is a danger of spontaneous heating and ignition when biochar is tightly packed. This occurs because fresh biochar quickly sorbs oxygen and moisture, and these sorption processes are exothermic, thus potentially leading to high temperature and ignition of the material.

- Volatile compounds present in certain biochar materials may also represent a fire hazard, but the amount of such compounds found in biochar can be managed by managing the pyrolysis temperature and heating rate. Certain chemicals can be added to biochar to decrease its flammability (e.g. boric acid, ferrous sulfate). The best way to prevent fire is to store and transport biochar in an atmosphere which excludes oxygen. Formulated biochar products such as mixtures with composts, manures, or the production of biochar-mineral complexes will potentially yield products which are much less flammable.

- For fine-grained biochars, wind losses can be significant (up to 30% loss has been reported). Biochar can be moistened, although this will add to the weight of the material and increase transportation costs. If wind loss is a concern, apply biochar when winds are mild and/or during a light rain. Pelleted biochars or mixing with other materials may reduce wind loss.

- To avoid water erosion, incorporate biochar into the soil.

- Application rates vary depending on the biochar and the intended use of the biochar.

- Biochar is relatively stable and recalcitrant. In some cases, biochar may improve soil conditions with time. Consequently, biochar application frequency is likely to be on the order of years.

- Biochar can be readily mixed with other materials, such as compost.

- The depth of biochar application varies with the intended purpose.

- For fertility applications, locate biochar near the soil surface in the active rooting zone.

- For moisture management, locate biochar throughout the root zone.

- For carbon sequestration, locate biochar deeper in the soil profile to reduce the likelihood of microbial mineralization.

- For stormwater applications, biochar can be broadcast and then incorporated into the soil. If fertility is the primary objective, banding may be utilized.

- For turf applications, biochar can be mixed with soil (sand and topsoil) and other amendments such as compost.

- Application rates depend on the intended use of a biochar. Field testing is recommended prior to application. Typical rates reported in the literature are 5-50 tonnes of biochar per hectare.

Sustainability

Because biochar is produced from biomass, including wastes, it is sustainable from an availability or supply standpoint. Sustainable biochar production, however, is less certain based on current economic constraints. Biochar has several potential markets and exploiting these markets is necessary for biochar production to be sustainable. Examples of specific markets include stormwater media, soil health and fertility, and carbon sequestration Biogreen (accessed December 10, 2019). Sustainable biochar production must also meet certain environmental and economic criteria, includign the following.

- Biochar systems should be, at a minimum, carbon and energy neutral.

- Biochar systems should prioritize the use of biomass residuals for biochar production.

- Biochar systems should be safe, clean, economical, efficient, and meet or exceed environmental standards and regulatory requirements of the regions where they are deployed.

- Biochar systems should promote or enhance ecological conditions for biodiversity at the local and landscape level.

- Biochar systems should not pollute or degrade water resources.

- Biochar systems should not jeopardize food security by displacing or degrading land grown for food; and should seek to complement existing local agro-ecological practices.

For more information, see the International Biochar Initiative discussion on sustainable biochar production. For a discussion of biochar sustainability, see sustainability and Certification (Vereijen et al., 2015).

References

- Agyarko-Mintah E, Cowie A, Singh BP, Joseph S, Van Zwieten L, Cowie A, Harden S, Smillie R.. 2017. Biochar increases nitrogen retention and lowers greenhouse gas emissions when added to composting poultry litter. Waste Manag. 61:138-149. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2016.11.027. Epub 2016 Dec 8.