Difference between revisions of "Karst"

m |

|||

| (17 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{alert|The Construction Stormwater Permit prohibits infiltration of stormwater runoff “within 1,000 feet up-gradient or 100 feet down-gradient of active karst features”. Active karst is a terrain having distinctive landforms and hydrology created primarily from the dissolution of soluble rocks within 50 feet of the land surface.|alert-danger}} | {{alert|The Construction Stormwater Permit prohibits infiltration of stormwater runoff “within 1,000 feet up-gradient or 100 feet down-gradient of active karst features”. Active karst is a terrain having distinctive landforms and hydrology created primarily from the dissolution of soluble rocks within 50 feet of the land surface.|alert-danger}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Technical information page image.png|right|100px|alt=image]] | ||

| + | [[File:Pdf image.png|100px|thumb|left|alt=pdf image|<font size=3>[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=File:Karst_-_Minnesota_Stormwater_Manual.pdf Download pdf]</font size>]] | ||

[[file:Check it out.png|200px|thumb|alt=check it out image|<font size=3>[https://gisdata.mn.gov/dataset/geos-surface-karst-feature-devel Minnesota Regions Prone to Surface Karst Feature Development].</font size>]] | [[file:Check it out.png|200px|thumb|alt=check it out image|<font size=3>[https://gisdata.mn.gov/dataset/geos-surface-karst-feature-devel Minnesota Regions Prone to Surface Karst Feature Development].</font size>]] | ||

| Line 7: | Line 10: | ||

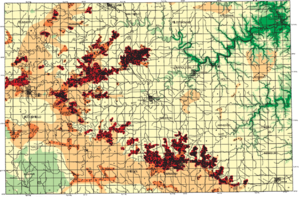

[[File:Fillmore County sinkhole probability map.png|thumb|300px|alt=statewide map illustrating karst areas|<font size=3>Map illustrating sinkhole probability in Fillmore County, Southeast Minnesota. The highest sinkhole densities are on flat hilltops between or adjacent to river valleys in the western half of the county (shown in red and orange). In these locations, limestone and dolomite is the first bedrock encountered and is typically within 50 feet of the land surface. Source: [http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/waters/programs/gw_section/mapping/platesum/fillcga.html Minnesota Department of Natural Resources], October 2005.</font size>]] | [[File:Fillmore County sinkhole probability map.png|thumb|300px|alt=statewide map illustrating karst areas|<font size=3>Map illustrating sinkhole probability in Fillmore County, Southeast Minnesota. The highest sinkhole densities are on flat hilltops between or adjacent to river valleys in the western half of the county (shown in red and orange). In these locations, limestone and dolomite is the first bedrock encountered and is typically within 50 feet of the land surface. Source: [http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/waters/programs/gw_section/mapping/platesum/fillcga.html Minnesota Department of Natural Resources], October 2005.</font size>]] | ||

| − | Karst geology makes up approximately 20 percent of the land surface in the United States. It is also found in other parts of the world such as China, Europe, the Caribbean, Australia, and Madagascar ([http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2008/5023/pdf/06hollings.pdf USGS]). Karst regions in Minnesota are predominantly found in the southeastern portion of the state. Use of infiltration BMPs in karst regions can be complicated and necessitates additional geotechnical testing, pre-treatment of stormwater runoff, and ponding of runoff. Caution must be used in interpreting the geographic depiction of karst lands as subsurface conditions can change rapidly over very short distances ([https://chesapeakestormwater.net/ | + | Karst geology makes up approximately 20 percent of the land surface in the United States. It is also found in other parts of the world such as China, Europe, the Caribbean, Australia, and Madagascar ([http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2008/5023/pdf/06hollings.pdf USGS]). Karst regions in Minnesota are predominantly found in the southeastern portion of the state. Use of infiltration BMPs in karst regions can be complicated and necessitates additional geotechnical testing, pre-treatment of stormwater runoff, and ponding of runoff. Caution must be used in interpreting the geographic depiction of karst lands as subsurface conditions can change rapidly over very short distances ([https://chesapeakestormwater.net/stormwater-guidance-for-karst-terrain/ Karst Working Group], 2009). Generalized maps of active karst will be less accurate than a county-scale map, as demonstrated by the two figures to the right. The following county-level maps have been developed. |

*[http://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/58436/sinkholes%5B1%5D.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y Olmsted] | *[http://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/58436/sinkholes%5B1%5D.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y Olmsted] | ||

*[http://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/58557/plate5%5B1%5D.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y Wabasha] | *[http://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/58557/plate5%5B1%5D.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y Wabasha] | ||

| Line 127: | Line 130: | ||

*Log any indications of water saturation to include both perched and groundwater table levels; include descriptions of soils that are mottled or gleyed. Be aware that ground water levels in karst can change dramatically in short periods of time and will not necessarily leave mottled or gleyed evidence. | *Log any indications of water saturation to include both perched and groundwater table levels; include descriptions of soils that are mottled or gleyed. Be aware that ground water levels in karst can change dramatically in short periods of time and will not necessarily leave mottled or gleyed evidence. | ||

*Record water levels in all borings over a time-period reflective of anticipated water level fluctuation, noting that water levels in karst geology can vary dramatically and rapidly. Borings should remain fully open to a total depth reflective of these variations and over a time that will accurately show the variation. Be advised that to get a complete picture, this could be a long-term period. Measurements could of course be collected during a period of operation of a BMP, which could be adjusted based on the findings of the data collection. | *Record water levels in all borings over a time-period reflective of anticipated water level fluctuation, noting that water levels in karst geology can vary dramatically and rapidly. Borings should remain fully open to a total depth reflective of these variations and over a time that will accurately show the variation. Be advised that to get a complete picture, this could be a long-term period. Measurements could of course be collected during a period of operation of a BMP, which could be adjusted based on the findings of the data collection. | ||

| − | *Estimate soil engineering characteristics, including “N” or estimated [ | + | *Estimate soil engineering characteristics, including “N” or estimated [https://www.iricen.gov.in/LAB/res/html/Test-37.html#:~:text=Unconfined%20Compressive%20Strength%20(UCS)%20stands,shear%20strength%20of%20clayey%20soil. unconfined compressive strength], when conducting a [https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/standard-penetration-test standard penetration test] (SPT). |

===Evaluation of findings=== | ===Evaluation of findings=== | ||

| Line 133: | Line 136: | ||

===Geophysical and dye techniques=== | ===Geophysical and dye techniques=== | ||

| − | Stormwater managers in need of subsurface geophysical surveys are encouraged to obtain the services of a qualified geophysicist experienced in karst geology. Some of the [https:// | + | Stormwater managers in need of subsurface geophysical surveys are encouraged to obtain the services of a qualified geophysicist experienced in karst geology. Some of the [https://files.dnr.state.mn.us/waters/groundwater_section/geophysics/reports/mystery_karst.pdf geophysical techniques] available for use in karst terrain include: seismic refraction, ground-penetrating radar, and electric resistivity. The surest way to determine the flow path of water in karst geology is to inject dye into the karst feature (sinkhole or fracture) and watch to see where it emerges, usually from a spring. The emergence of a known dye from a spring grants certainty to a suspicion that ground water moves in a particular pattern. Dye tracing can vary substantially in cost depending upon the local karst complexity, but it can be a reasonably priced alternative, especially when the certainty is needed. |

{{alert|Dye tracing requires expertise and should only be done by experienced karst hydrogeologists. Contact the [http://www.mngs.umn.edu/about.html Minnesota Geological Survey] for more information.|alert-warning}} | {{alert|Dye tracing requires expertise and should only be done by experienced karst hydrogeologists. Contact the [http://www.mngs.umn.edu/about.html Minnesota Geological Survey] for more information.|alert-warning}} | ||

| − | + | For good basic information on use of dye techniques in karst settings, see the United States EPA document, [http://karstwaters.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/dye-tracing.pdf Application of Dye-tracing techniques for Determining Solute-transport Characteristics of Ground Water in Karst Terranes] (1988). | |

==General stormwater management guidelines for karst areas== | ==General stormwater management guidelines for karst areas== | ||

| Line 144: | Line 147: | ||

In karst settings there are special considerations and potentially additional constraints needed prior to implementing most structural BMPs. A growing emphasis is being placed on the implementation of strategies that preserve the pre-development hydrology and maintain critical vegetated areas. This is based on the idea that, in a pre-development setting, the runoff was spread across the landscape rather than directed to a certain area, which often results when there is a high concentration of pervious surfaces. When stormwater is concentrated in one area, it can lead to a more rapid dissolution of the underlying rock. | In karst settings there are special considerations and potentially additional constraints needed prior to implementing most structural BMPs. A growing emphasis is being placed on the implementation of strategies that preserve the pre-development hydrology and maintain critical vegetated areas. This is based on the idea that, in a pre-development setting, the runoff was spread across the landscape rather than directed to a certain area, which often results when there is a high concentration of pervious surfaces. When stormwater is concentrated in one area, it can lead to a more rapid dissolution of the underlying rock. | ||

| − | The uncertainty related to the actual presence of karst, the presence of unstable materials that have the potential for development of karst, and the water movement through karst terrain dictates the level of additional field information to be collected before proceeding with BMP design and construction in Active Karst and Transitional Karst classifications. The following guidelines are based on adaptations from a handful of communities (e.g., Carroll County, MD (2004a and b); St. Johns River Water Management District, FL (2010); Jefferson County, WV (Laughland 2003); [https://tnpermanentstormwater.org/manual/27%20Appendix%20B%20Stormwater%20Design%20Guidelines%20for%20Karst%20Terrain.pdf Tennessee Permanent Stormwater Management and Design Guidance Manual – Appendix B] (2014); and other documents ([ | + | The uncertainty related to the actual presence of karst, the presence of unstable materials that have the potential for development of karst, and the water movement through karst terrain dictates the level of additional field information to be collected before proceeding with BMP design and construction in Active Karst and Transitional Karst classifications. The following guidelines are based on adaptations from a handful of communities (e.g., Carroll County, MD (2004a and b); St. Johns River Water Management District, FL (2010); Jefferson County, WV (Laughland 2003); [https://tnpermanentstormwater.org/manual/27%20Appendix%20B%20Stormwater%20Design%20Guidelines%20for%20Karst%20Terrain.pdf Tennessee Permanent Stormwater Management and Design Guidance Manual – Appendix B] (2014); and other documents ([https://chesapeakestormwater.net/technical-bulletin-no-1-stormwater-design-guidelines-for-karst-terrain/ Chesapeake Stormwater Network], [https://chesapeakestormwater.net/stormwater-guidance-for-karst-terrain/ Karst Working Group, 2009]; [http://www.dep.wv.gov/WWE/Programs/stormwater/MS4/Documents/Appendix_C_Stormwater_Mgmt_Design_Karst_WV-SW-11-2012.pdf West Virginia Stormwater Management & Design Guidance Manual]). |

The following guidelines do not contain substantial prescriptive information because of the variability inherent to karst geology in Minnesota. | The following guidelines do not contain substantial prescriptive information because of the variability inherent to karst geology in Minnesota. | ||

| Line 152: | Line 155: | ||

*Minimize the area of impervious surfaces at the site. This will reduce the volume and velocity of the stormwater runoff. Consult with a geotechnical engineer prior to the design and construction of a BMP. | *Minimize the area of impervious surfaces at the site. This will reduce the volume and velocity of the stormwater runoff. Consult with a geotechnical engineer prior to the design and construction of a BMP. | ||

*Capture the runoff in a series of small runoff reduction practices where sheet flow is present. This technique will help keep the stormwater runoff from becoming channelized and will disperse the flow over a broad area. Practices such as [[Filtration|swales]], [[Bioretention|bioretention with underdrains]], [[Filtration|media filters]], and [[Vegetated filter strips|vegetated filters]] should be considered first at a site. However, not all sites lend themselves to this type of management approach. Adequate precautions should be taken to assure that runoff water is adequately [[Pre-treatment|pretreated]]. | *Capture the runoff in a series of small runoff reduction practices where sheet flow is present. This technique will help keep the stormwater runoff from becoming channelized and will disperse the flow over a broad area. Practices such as [[Filtration|swales]], [[Bioretention|bioretention with underdrains]], [[Filtration|media filters]], and [[Vegetated filter strips|vegetated filters]] should be considered first at a site. However, not all sites lend themselves to this type of management approach. Adequate precautions should be taken to assure that runoff water is adequately [[Pre-treatment|pretreated]]. | ||

| − | *Design BMPs to be | + | *Design BMPs to be <span title="a flow system where only stormwater runoff treated by a BMP enters the BMP, with remaining water bypassing the BMP"> '''off-line'''</span> such that volumes of runoff greater than the capacity of the BMP are bypassed around the BMP. This approach will limit the volume through the BMP to a quantity that is manageable in the karst. |

*Install multiple small BMPs instead of a centralized BMP. Centralized BMPs are defined as any practice that treats runoff from a contributing drainage area greater than 20,000 square feet, and/or has a surface ponding depth greater than 3 feet. Centralized practices have the greatest potential for karst- related failure, and will require costly geotechnical investigations and a more complex design. | *Install multiple small BMPs instead of a centralized BMP. Centralized BMPs are defined as any practice that treats runoff from a contributing drainage area greater than 20,000 square feet, and/or has a surface ponding depth greater than 3 feet. Centralized practices have the greatest potential for karst- related failure, and will require costly geotechnical investigations and a more complex design. | ||

*Direct discharge from stormwater BMPs to surface waters and not to the nearest sinkhole. Because karst areas can be quite large in Minnesota, discharges should be routed to a baseflow stream via a pipe or lined ditch or channel to redirect the flow away from the karst, provided the stream does not disappear into a karst feature. | *Direct discharge from stormwater BMPs to surface waters and not to the nearest sinkhole. Because karst areas can be quite large in Minnesota, discharges should be routed to a baseflow stream via a pipe or lined ditch or channel to redirect the flow away from the karst, provided the stream does not disappear into a karst feature. | ||

*Design [[Stormwater ponds|ponds]] and [[Stormwater wetlands|wetlands]] with a properly engineered [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Liners_for_stormwater_management synthetic liner]. It is HIGHLY RECOMMENDED that a professional geotechnical engineer investigate and recommend the depth of unconsolidated material between the bottom of the pond and the surface of the bedrock. A minimum of 3 feet of unconsolidated soil material is the minimum separation; however an expert may recommend 10 feet or greater. Pond and wetland depths should be fairly uniform and limited to no more than 10 feet in depth. | *Design [[Stormwater ponds|ponds]] and [[Stormwater wetlands|wetlands]] with a properly engineered [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Liners_for_stormwater_management synthetic liner]. It is HIGHLY RECOMMENDED that a professional geotechnical engineer investigate and recommend the depth of unconsolidated material between the bottom of the pond and the surface of the bedrock. A minimum of 3 feet of unconsolidated soil material is the minimum separation; however an expert may recommend 10 feet or greater. Pond and wetland depths should be fairly uniform and limited to no more than 10 feet in depth. | ||

| − | {{alert| | + | |

| + | {{alert|Section 18.10 of the Construction Stormwater permit requires that "Permittees must design basins using an impermeable liner if located within active karst terrain".|alert-danger}} | ||

| + | {{alert|At sites within areas of active karst and that do not require a Construction Stormwater permit, a geotechnical investigation following guidance on this page is highly recommended.|alert-warning}} | ||

| + | |||

*Minimize site disturbance during BMP construction. Seek the recommendations of a geotechnical engineer for management of heavy equipment, temporary storage of materials, changes to the soil profile - including cuts, fills, excavation and drainage alteration - on sites that have been found to contain a karst feature. | *Minimize site disturbance during BMP construction. Seek the recommendations of a geotechnical engineer for management of heavy equipment, temporary storage of materials, changes to the soil profile - including cuts, fills, excavation and drainage alteration - on sites that have been found to contain a karst feature. | ||

*Report sinkholes as soon as possible after the first observation of sinkhole development. The sinkhole(s) should then be repaired or the stormwater management facility abandoned, adapted, managed and/or observed for future changes, whichever of these is most appropriate. | *Report sinkholes as soon as possible after the first observation of sinkhole development. The sinkhole(s) should then be repaired or the stormwater management facility abandoned, adapted, managed and/or observed for future changes, whichever of these is most appropriate. | ||

| Line 172: | Line 178: | ||

Additional information on sinkhole remediation can be found at: | Additional information on sinkhole remediation can be found at: | ||

*[http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1109&context=sinkhole_2013 Problems Associated with the Use of Compaction Grout for Sinkhole Remediation in West-Central Florida] (Zisman, 2013). This paper presents information regarding the improper application of compaction grouting in sinkholes. | *[http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1109&context=sinkhole_2013 Problems Associated with the Use of Compaction Grout for Sinkhole Remediation in West-Central Florida] (Zisman, 2013). This paper presents information regarding the improper application of compaction grouting in sinkholes. | ||

| − | *[ | + | *[https://potomacpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/RobDenton_KarstTopography.pdf The Characterization and Remediation of Sinkholes] (Denton, N.D. – PowerPoint Presentation). The PowerPoint presentation presents an overview of karst geology and some common remediation techniques. |

*[http://cedb.asce.org/cgi/WWWdisplay.cgi?256932 Development Mechanism and Remediation of Multiple Spontaneous Sinkholes: A Case Study] (Jammal et al., 2010). This journal article provides information on how to remediate when multiple sinkholes are present. | *[http://cedb.asce.org/cgi/WWWdisplay.cgi?256932 Development Mechanism and Remediation of Multiple Spontaneous Sinkholes: A Case Study] (Jammal et al., 2010). This journal article provides information on how to remediate when multiple sinkholes are present. | ||

| − | *[ | + | *[https://www.hydroreview.com/world-regions/sinkholes-and-seepage-embankment-repair-at-hat-creek-1/#gref Sinkholes and Seepage: Embankment Repair at Hat Creek 1] (Bowers et al., 2013). This article discusses geotechnical investigation and engineering solution regarding a sinkhole that was discovered near a Pacific Gas and Electric Company hydroelectric project. |

*[http://tnpermanentstormwater.org/manual/27%20Appendix%20B%20Stormwater%20Design%20Guidelines%20for%20Karst%20Terrain.pdf Tennessee Permanent Stormwater Management and Design Guidance Manual – Appendix B] (2014). This section of Appendix B provides a brief overview of sinkhole notification, investigation, stabilization, and final grading. | *[http://tnpermanentstormwater.org/manual/27%20Appendix%20B%20Stormwater%20Design%20Guidelines%20for%20Karst%20Terrain.pdf Tennessee Permanent Stormwater Management and Design Guidance Manual – Appendix B] (2014). This section of Appendix B provides a brief overview of sinkhole notification, investigation, stabilization, and final grading. | ||

| Line 181: | Line 187: | ||

Below is a list of resources that provide additional information on runoff and/or groundwater monitoring in karst areas. | Below is a list of resources that provide additional information on runoff and/or groundwater monitoring in karst areas. | ||

| − | *[ | + | *[https://karstwaters.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/gw-monitoring-in-karst.pdf Ground-Water Monitoring in Karst Terranes: Recommended Protocols & Implicit Assumptions] (EPA, 1989). This report provides information on the monitoring procedures and common monitoring pitfalls in karst areas. It describes where to monitor for pollutants, where to monitor for background water quality, when to monitor the groundwater, and how to do all this reliably and economically. |

| − | *''Highway Stormwater Runoff in Karst Areas – Preliminary Results of Baseline Monitoring and Design of a Treatment System for a Sinkhole in Knoxville Texas'' ([ | + | *''Highway Stormwater Runoff in Karst Areas – Preliminary Results of Baseline Monitoring and Design of a Treatment System for a Sinkhole in Knoxville Texas'' ([https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0013795298000544 Stephenson et al.], 1999). The authors of this report discuss the use of quantitative dye tracing and hydrograph analyses to monitor stormwater runoff and resulting groundwater flow from runoff from a highway system. |

*[http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2414&context=theses Evaluating the Effectiveness of Regulatory Stormwater Monitoring Protocols on Groundwater Quality in Urbanized Karst Regions] (Nedvidek, 2014). This report looks at monitoring techniques and frequencies. It also discusses how to make these monitoring programs cost effective, while still providing a sufficient amount of information. | *[http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2414&context=theses Evaluating the Effectiveness of Regulatory Stormwater Monitoring Protocols on Groundwater Quality in Urbanized Karst Regions] (Nedvidek, 2014). This report looks at monitoring techniques and frequencies. It also discusses how to make these monitoring programs cost effective, while still providing a sufficient amount of information. | ||

| Line 189: | Line 195: | ||

*if waters of the state are or may be impacted, contact the state duty officer (651-649-5451 or 800-422-0798; or 651-297-5353 TDD Line/800-627-3529 TDD Watts Line); | *if waters of the state are or may be impacted, contact the state duty officer (651-649-5451 or 800-422-0798; or 651-297-5353 TDD Line/800-627-3529 TDD Watts Line); | ||

*contact appropriate local authorities; and/or | *contact appropriate local authorities; and/or | ||

| − | *repair the practice [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Karst | + | *repair the practice [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Karst#How_to_remediate_after_a_sinkhole_appears following guidance above]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Related pages== | ==Related pages== | ||

| Line 215: | Line 217: | ||

<noinclude> | <noinclude> | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Level 2 - Technical and specific topic information/infiltration]] |

</noinclude> | </noinclude> | ||

Latest revision as of 15:57, 31 January 2023

Karst geology makes up approximately 20 percent of the land surface in the United States. It is also found in other parts of the world such as China, Europe, the Caribbean, Australia, and Madagascar (USGS). Karst regions in Minnesota are predominantly found in the southeastern portion of the state. Use of infiltration BMPs in karst regions can be complicated and necessitates additional geotechnical testing, pre-treatment of stormwater runoff, and ponding of runoff. Caution must be used in interpreting the geographic depiction of karst lands as subsurface conditions can change rapidly over very short distances (Karst Working Group, 2009). Generalized maps of active karst will be less accurate than a county-scale map, as demonstrated by the two figures to the right. The following county-level maps have been developed.

In Minnesota there are three classifications of karst lands.

- Active Karst. Active karst is a terrain having distinctive landforms and hydrology created primarily from the dissolution of soluble rocks within 50 feet of the land surface

- Transition Karst. Transition karst is defined as areas underlain by carbonate bedrock with 50 to 100 feet of sediment cover.

- Covered Karst. Covered karst is defined as areas underlain by carbonate bedrock but with more than 100 feet of sediment cover.

A site with Active Karst has the greatest potential for development of a sinkhole below a BMP and the recommendations contained in this section should be considered for all proposed BMPs in areas with Active Karst. For Transitional Karst sites, it is HIGHLY RECOMMENDED that the nature of the overlying soils be evaluated with respect to the potential for catastrophic failure given the increase in hydrostatic pressure created by a BMP.

- Recommended websites pertaining to Minnesota karst

Contents

- 1 What is karst?

- 2 Why is karst geology a concern?

- 3 Where can I get more information on karst in Minnesota?

- 4 How to investigate for karst on a site

- 5 General stormwater management guidelines for karst areas

- 6 How to remediate after a sinkhole appears

- 7 Monitoring of BMPs in karst regions

- 8 Related pages

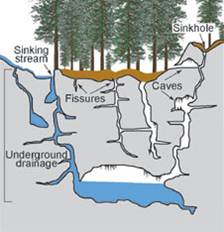

What is karst?

Karst is a landscape formed by the dissolution of a layer or layers of soluble bedrock. The bedrock is usually carbonate rock such as limestone or dolomite but the dissolution has also been documented in weathering resistant rock, such as quartz. The dissolution of the rocks occurs due to the reaction of the rock with acidic water. Rainfall is already slightly acidic due to the absorption of carbon dioxide (CO2), and becomes more so as it passes through the subsurface and picks up even more CO2. Cracks and fissures form as the runoff passes through the subsurface and reacts with the rocks. These cracks and fissures grow, creating larger passages, caves, and may even form sinkholes as more and more acidic water infiltrates into the subsurface (American Rivers).

Subterranean drainage through karst geology limits the presence of surface water in places, explaining the absence of rivers and lakes. Many karst regions display distinctive surface features such as a sinkhole or natural pit (often termed cenotes or dolines), fissures, or caves (USGS, 2012). However, distinctive karst surface features may be completely absent where the soluble rock is below a deep layer of glacial debris (termed mantled), or is below one or more layers of non-soluble rock strata. Some karst regions include thousands of caves, although evidence of caves large enough for human exploration is not a required characteristic of karst.

Presence of sinkholes is an absolute indication of active karst. In these cases, an easement or reserve area should be identified on the development plans for the project so that all future landowners know of the presence of active karst on their property.

The following sources provide additional information on karst in Minnesota.

- Karst in Minnesota - Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

- Karst features of Minnesota - Minnesota Geological Survey

- THE DEVELOPMENT OF A KARST FEATURE DATABASE FOR SOUTHEASTERN MINNESOTA - Alexander and Tipping

Why is karst geology a concern?

Infiltration BMPs in karst settings have the potential of creating sinkholes as a result of the additional weight of water in a structural BMP (termed hydraulic head) and/or water infiltrated from the BMP that can dissolve the carbonate rock (e.g., limestone). These conditions can lead to the erosion of bedrock underneath or adjacent to a BMP. In addition, the pollutants being carried by the stormwater runoff can pass rapidly through the subsurface into the groundwater, creating a greater risk of groundwater contamination than is found in other soil types.

Where karst conditions exist, there are no prescriptive rules or universally accepted management approaches. When underlying karst is known or suspected to be present at the site, stormwater runoff should not be concentrated and discharged into or near known sinkholes. Instead, the following strategies should be employed.

- Runoff should be dispersed

- Runoff should be pretreated and then infiltrated only if subsurface investigations and geotechnical analysis confirm that there are no unstable zones below the BMP

- Additional borings and deeper borings may be warranted to target evaluation of transitional karst zone

- Once ponds are constructed, include contingency plans for cases where karst features open up and impact a pond, including conducting geotechnical borings to appropriate depths trying to identify unstable zones, then target those zones for grouting

- Convey runoff to a collection and transmission system away from the area via vegetated drainageways

Where can I get more information on karst in Minnesota?

The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources has a relatively new product, Minnesota Regions Prone to Surface Karst Feature Development: GW-01, that shows karst areas in MN. This product can be used to outline such areas in a GIS environment. The GIS coverage is a superposition of Bedrock Geology and Depth to Bedrock maps prepared by the Minnesota Geological Survey (MGS). This dataset is managed by the Ecological and Water Resources Division, County Geologic Atlas Program. For additional information, visit Springs, Springsheds, and Karst on the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources website.

How to investigate for karst on a site

Developers, communities, public works agents, and other stormwater managers should conduct site investigations prior to designing and implementing stormwater BPMs in both active and transitional karst areas. A site with active karst has the greatest potential for development of a sinkhole below a BMP and the recommendations contained in this section should be considered for all proposed BMPs. For transitional karst sites, it is HIGHLY RECOMMENDED that the nature of the overlaying soils be evaluated with respect to the potential for catastrophic failure given the increase in hydrostatic pressure created by a BMP. The level of investigation required will depend on the likelihood of karst being present and the regulatory requirements in the area.

The purpose of the investigation is to identify subsurface voids, cavities, fractures, or other discontinuities which could pose an environmental concern or a construction hazard to an existing or proposed stormwater management facility. Of special concern are the construction hazards posed by karst geology, the formation of sinkholes, and the possibility of a preferential pathway that would provide a direct route for polluted runoff to enter the regional groundwater system. Because of the complexity inherent to active and transitional karst areas, there is no single set of investigatory guidelines that works for every location. Typically, however, the first step is a preliminary investigation that involves analyzing geological and topographic county maps, and aerial photography to determine if active karst is known to be present. Included in the preliminary investigation should be a site visit to perform a visual observation for karst features such as sinkholes. Results of the investigation should be reported to the appropriate agency, including the Department of Natural Resources (DNR), Minnesota Geological Survey (MGS), and local agencies (such as the city, township or county). These known and discovered karst features should be surveyed for specific location and permanently recorded on the property deed.

If it is determined that active karst is present, a detailed site investigation, including a subsurface materials investigation should be conducted. The design of any geotechnical investigation should reflect the size and complexity of the proposed project, as well as the local knowledge of the threat posed by the karstic geology. The geotechnical investigation should first assess the subsurface heterogeneity (variability). With this information in-hand, borings or observation wells can then be accurately installed to obtain vertical data surrounding or within karst features or within areas of instability that have the potential for development of karst. The vertical data should be used to determine the nature and thickness of the subsurface materials and needs to include information involving depth to the bedrock and depth to the groundwater table. The investigation will be an iterative process and should be expanded until the desired detailed knowledge of the site is obtained and fully understood (Karst Working Group, 2009). Guidelines for investigating all potential physical constraints to infiltration on a site are presented in a table at this link. These guidelines should not be interpreted as all-inclusive. The size and complexity of the project will drive the extent of any subsurface investigation.

Additional information regarding site investigations in karst areas can be found in Appendix B of the Tennessee Permanent Stormwater Management and Design Guidance Manual (Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, 2014). The Tennessee manual provides a flowchart which will guide designers through the investigative process and will help designers determine if any special analysis is required.

Preliminary site investigation

The level of detail required for a site investigation will depend on the likelihood that karst is present and on any local regulations. The preliminary site investigation should include, but not be limited to

- a review of aerial photographs, geological literature, sinkhole maps, previous soil borings, existing well data, and municipal wellhead or aquifer protection plans;

- a site reconnaissance, including a thorough field examination for features such as limestone pinnacles, sinkholes, closed depressions, fracture traces, faults, springs, and seeps; and

- site observations made under varying weather conditions, especially during heavy rains and in different seasons to identify and map any natural drainageways.

Subsurface material investigation

The investigation should determine the nature and thickness of subsurface materials, including depth to bedrock and the water table. Subsurface data may be acquired by backhoe excavation and/or soil boring. These field data should be supplemented by geophysical investigation techniques deemed appropriate by a qualified professional, which will show the location of karst formations under the surface. This is an iterative process that might need to be repeated until the desired detailed knowledge of the site is obtained and fully understood. The data listed below should be acquired under the direct supervision of a qualified and experienced karst scientist.

- Bedrock characteristics (ex. type, geologic contacts, faults, geologic structure, rock surface configuration)

- Depth to the water table and depth to bedrock

- Type and percent of coarse fragements

- Soil characteristics (ex. color, type, thickness, mapped unit, geologic source/history)

- Photo-geologic fracture trace map

- Bedrock outcrop areas

- Sinkholes and/or other closed depressions

- Perennial and/or intermittent streams, and their flow behavior (ex. a stream in a karst area that loses volume could be a good indication of sinkhole infiltration)

In conducting subsurface investigations, all applicable State regulations must be met. For more information, see Minnesota Department of Health's Wells and Borings website.

Location of soil borings

The local variability typical of karst areas could mean that a very different subsurface could exist close by, perhaps as little as 6 inches away. To accommodate this variability, the number and type of borings must be carefully assessed. If the goal is to locate a boring down the center of a sinkhole, the previous geophysical tests or excavation results can show the likely single location to achieve that goal. If the goal is to “characterize” the entire site, then an evaluation needs to occur to determine the number and depth needed to adequately represent the site. Again, the analyst must acknowledge the extreme variability and recognize that details can easily be missed. Some general guidance for locating borings include:

- getting at least 1 boring in each distinct major soil type present, as mapped in soil surveys;

- placing an adequate number near on-site geologic or geomorphic indications of the presence of sinkholes or related karst features;

- locating along geologic fracture traces;

- locating adjacent to bedrock outcrop areas;

- locating a sufficient number to adequately represent the area under any proposed stormwater facility; and

- documenting any areas identified as anomalies from any existing geophysical or other subsurface studies.

Exploratory borings must comply with Minnesota statutes, 4727.0100

Number and depth of soil borings

The number and depth of borings depends upon the results of the subsurface evaluation obtained from the observational, geophysical, and excavation studies, as well as other borings. There are no prescriptive guidelines to determine the number and depth of borings. These will have to be determined by the qualified staff conducting the BMP management evaluation and will be based upon the data needs of the installation. The borings must extend well below the bottom elevation of the designed BMP to ensure there are no karst features that will be encountered or impacted as a result of the installation.

At least 1 subsurface cross section should be provided for the BMP installation, showing confining layers, depth to bedrock, and water table (if encountered). It should extend through a central portion of the proposed installation, using the actual geophysical and boring data. A sketch map or formal construction plan indicating the location and dimension of the proposed practice and line of cross section should be included for reference, or as a base map for presentation of subsurface data.

Abandoning soil borings

Under Minnesota law all soil borings must be sealed by a licensed well contractor or a licensed well sealing contractor. A property owner may not seal any well or boring. See Minnesota Statutes, Chapter 103I For more information see these Minnesota Department of Health websites.

Identification of material

All material identified by the excavation and geophysical studies and penetrated by the boring should be identified, as follows.

- Provide descriptions, logging, and sampling for the entire depth of the boring.

- Note any stains, odors, or other indications of environmental degradation.

- Perform laboratory analysis on a minimum of 2 soil samples, representative of the material penetrated, including potential limiting soil horizons, with the results compared to the field descriptions.

- Identify soil characteristics including color, mineral composition, grain size, shape, sorting, and degree of saturation.

- Log any indications of water saturation to include both perched and groundwater table levels; include descriptions of soils that are mottled or gleyed. Be aware that ground water levels in karst can change dramatically in short periods of time and will not necessarily leave mottled or gleyed evidence.

- Record water levels in all borings over a time-period reflective of anticipated water level fluctuation, noting that water levels in karst geology can vary dramatically and rapidly. Borings should remain fully open to a total depth reflective of these variations and over a time that will accurately show the variation. Be advised that to get a complete picture, this could be a long-term period. Measurements could of course be collected during a period of operation of a BMP, which could be adjusted based on the findings of the data collection.

- Estimate soil engineering characteristics, including “N” or estimated unconfined compressive strength, when conducting a standard penetration test (SPT).

Evaluation of findings

At least 1 figure showing the subsurface soil profile cross section through the proposed practice should be provided, showing confining layers, depth to bedrock, and water table (if encountered). It should extend through a central portion of the proposed practice, using the actual or projected boring data. A sketch map or formal construction plan indicating the location and dimension of the proposed practice and line of cross section should be included for reference, or as a base map for presentation of subsurface data.

Geophysical and dye techniques

Stormwater managers in need of subsurface geophysical surveys are encouraged to obtain the services of a qualified geophysicist experienced in karst geology. Some of the geophysical techniques available for use in karst terrain include: seismic refraction, ground-penetrating radar, and electric resistivity. The surest way to determine the flow path of water in karst geology is to inject dye into the karst feature (sinkhole or fracture) and watch to see where it emerges, usually from a spring. The emergence of a known dye from a spring grants certainty to a suspicion that ground water moves in a particular pattern. Dye tracing can vary substantially in cost depending upon the local karst complexity, but it can be a reasonably priced alternative, especially when the certainty is needed.

For good basic information on use of dye techniques in karst settings, see the United States EPA document, Application of Dye-tracing techniques for Determining Solute-transport Characteristics of Ground Water in Karst Terranes (1988).

General stormwater management guidelines for karst areas

In karst settings there are special considerations and potentially additional constraints needed prior to implementing most structural BMPs. A growing emphasis is being placed on the implementation of strategies that preserve the pre-development hydrology and maintain critical vegetated areas. This is based on the idea that, in a pre-development setting, the runoff was spread across the landscape rather than directed to a certain area, which often results when there is a high concentration of pervious surfaces. When stormwater is concentrated in one area, it can lead to a more rapid dissolution of the underlying rock.

The uncertainty related to the actual presence of karst, the presence of unstable materials that have the potential for development of karst, and the water movement through karst terrain dictates the level of additional field information to be collected before proceeding with BMP design and construction in Active Karst and Transitional Karst classifications. The following guidelines are based on adaptations from a handful of communities (e.g., Carroll County, MD (2004a and b); St. Johns River Water Management District, FL (2010); Jefferson County, WV (Laughland 2003); Tennessee Permanent Stormwater Management and Design Guidance Manual – Appendix B (2014); and other documents (Chesapeake Stormwater Network, Karst Working Group, 2009; West Virginia Stormwater Management & Design Guidance Manual).

The following guidelines do not contain substantial prescriptive information because of the variability inherent to karst geology in Minnesota.

- Conduct a thorough geotechnical investigation in areas with suspected or documented active karst. Karst geology can change rapidly over very short distances so additional soil borings may be required in comparison to geotechnical investigations for shallow groundwater or bedrock.

- Investigate non-infiltration BMPs on sites where infiltration is not allowed under requirements of the CGP (i.e. where the BMP would be “within 1,000 feet up-gradient or 100 feet down-gradient of active karst features”).

- Preserve the maximum length of natural swales as possible at the site to increase the infiltration and accommodate flows from extreme storms.

- Minimize the area of impervious surfaces at the site. This will reduce the volume and velocity of the stormwater runoff. Consult with a geotechnical engineer prior to the design and construction of a BMP.

- Capture the runoff in a series of small runoff reduction practices where sheet flow is present. This technique will help keep the stormwater runoff from becoming channelized and will disperse the flow over a broad area. Practices such as swales, bioretention with underdrains, media filters, and vegetated filters should be considered first at a site. However, not all sites lend themselves to this type of management approach. Adequate precautions should be taken to assure that runoff water is adequately pretreated.

- Design BMPs to be off-line such that volumes of runoff greater than the capacity of the BMP are bypassed around the BMP. This approach will limit the volume through the BMP to a quantity that is manageable in the karst.

- Install multiple small BMPs instead of a centralized BMP. Centralized BMPs are defined as any practice that treats runoff from a contributing drainage area greater than 20,000 square feet, and/or has a surface ponding depth greater than 3 feet. Centralized practices have the greatest potential for karst- related failure, and will require costly geotechnical investigations and a more complex design.

- Direct discharge from stormwater BMPs to surface waters and not to the nearest sinkhole. Because karst areas can be quite large in Minnesota, discharges should be routed to a baseflow stream via a pipe or lined ditch or channel to redirect the flow away from the karst, provided the stream does not disappear into a karst feature.

- Design ponds and wetlands with a properly engineered synthetic liner. It is HIGHLY RECOMMENDED that a professional geotechnical engineer investigate and recommend the depth of unconsolidated material between the bottom of the pond and the surface of the bedrock. A minimum of 3 feet of unconsolidated soil material is the minimum separation; however an expert may recommend 10 feet or greater. Pond and wetland depths should be fairly uniform and limited to no more than 10 feet in depth.

- Minimize site disturbance during BMP construction. Seek the recommendations of a geotechnical engineer for management of heavy equipment, temporary storage of materials, changes to the soil profile - including cuts, fills, excavation and drainage alteration - on sites that have been found to contain a karst feature.

- Report sinkholes as soon as possible after the first observation of sinkhole development. The sinkhole(s) should then be repaired or the stormwater management facility abandoned, adapted, managed and/or observed for future changes, whichever of these is most appropriate.

- Develop a contingency plan for how to manage the stormwater should a BMP fail as a result of the development of a karst feature.

- If a karst feature is encountered report to the appropriate state agency, such as the Department of Natural Resources (DNR), Minnesota Geological Survey (MGS), and local agencies (such as the city, township or county). These known occurrences should be surveyed for specific location and permanently recorded on the property deed. For transition karst areas, local discretion and the likelihood of karstic features should be used to determine the amount of geotechnical investigation. An easement or reserve area should be identified on the development plats for the project so that all future landowners know of the presence of active karst on their property.

- Incorporate additional precautions where infiltration practices are used. For example, infiltration of stormwater from stormwater hoptspots is discouraged unless pollutant concentrations can be significantly reduced through pretreatment practices.

Stormwater BMP selection in karst settings. Sources Karst Working Group, 2009; Minnesota Stormwater Wiki; Tennessee Permanent Stormwater Management and Design Guidance.

Link to this table

| BMP | Suitability in karst regions | Karst considerations | Construction stormwater permit restriction1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impervious area disconnect | Preferred |

|

No |

| Bioretention with underdrain (biofiltration) | Preferred |

|

No |

| Rain tank/cistern | Preferred |

|

No |

| Rooftop disconnect | Preferred |

|

No |

| Green roofs | Preferred |

|

No |

| Dry swale or grassed channel | Preferred |

Warning: If the CSW permit applies, Section 16.20 prohibits permittees from constructing infiltration systems in areas within 1,000 feet upgradient or 100 feet downgradient of active karst

|

Yes if designed for infiltration |

| Media filter | Preferred |

|

No |

| Vegetative filter | Preferred |

|

No |

| Soil compost amendment | Adequate | No | |

| Small scale infiltration/micro-bioinfiltration | Adequate |

Warning: If the CSW permit applies, Section 16.20 prohibits permittees from constructing infiltration systems in areas within 1,000 feet upgradient or 100 feet downgradient of active karst

|

Yes |

| Permeable pavement | Adequate | Warning: If the CSW permit applies, Section 16.20 prohibits permittees from constructing infiltration systems in areas within 1,000 feet upgradient or 100 feet downgradient of active karst |

Yes if designed for infiltration (no underdrain) |

| Infiltration trench or basin | Adequate |

Warning: If the CSW permit applies, Section 16.20 prohibits permittees from constructing infiltration systems in areas within 1,000 feet upgradient or 100 feet downgradient of active karst

|

Yes |

| Constructed wetlands | Adequate |

Warning: If the CSW permit applies, liners are required in areas of active karst

|

No |

| Dry extended detention (ED) ponds and wet ponds | Adequate |

Warning: If the CSW permit applies, liners are required in areas of active karst |

No |

| Wet swale | Discouraged | Not feasible | No |

| Large scale infiltration | Discouraged |

Warning: If the CSW permit applies, Section 16.20 prohibits permittees from constructing infiltration systems in areas within 1,000 feet upgradient or 100 feet downgradient of active karst

|

Yes |

1Section 16.20 of the CSW Permit prohibits prohibits permittees from constructing infiltration systems in areas within 1,000 feet upgradient or 100 feet downgradient of active karst features.

How to remediate after a sinkhole appears

There are several approaches to sinkhole remediation if such an approach is desirable. Sinkhole sealing involves investigation, stabilization, filling, and final grading. In the investigation phase, the areal extent and depth of the sinkhole(s) should be determined. The investigation may consist of excavation to bedrock, soil borings, and/or geophysical studies. Sealing small-sized sinkholes is normally achieved by digging out the sinkhole to bedrock, plugging the hole with concrete, installing several impermeable soil layers interspersed with plastic or geotextile, and crowning with an impermeable layer and topsoil. For moderate sinkholes, an engineered subsurface structure is usually required.

It is often not feasible to seal large sinkholes so other remediation options must be pursued. These could include construction of a low-head berm around the sinkhole, clean-out of the sinkhole to make sure all potentially contaminating materials are removed, landscaping and conversion of land use in the sinkhole to open space or recreation, provided it can be done in a manner that provides adequate safety. In any of these cases, pre-treatment of any stormwater entering the sinkhole is imperative. Final grading of sinkholes in open space settings should include the placement of low permeability topsoil or clay and a vegetative cover, with a positive grade maintained away from the sinkhole location to avoid ponding or infiltration, if feasible.

Additional information on sinkhole remediation can be found at:

- Problems Associated with the Use of Compaction Grout for Sinkhole Remediation in West-Central Florida (Zisman, 2013). This paper presents information regarding the improper application of compaction grouting in sinkholes.

- The Characterization and Remediation of Sinkholes (Denton, N.D. – PowerPoint Presentation). The PowerPoint presentation presents an overview of karst geology and some common remediation techniques.

- Development Mechanism and Remediation of Multiple Spontaneous Sinkholes: A Case Study (Jammal et al., 2010). This journal article provides information on how to remediate when multiple sinkholes are present.

- Sinkholes and Seepage: Embankment Repair at Hat Creek 1 (Bowers et al., 2013). This article discusses geotechnical investigation and engineering solution regarding a sinkhole that was discovered near a Pacific Gas and Electric Company hydroelectric project.

- Tennessee Permanent Stormwater Management and Design Guidance Manual – Appendix B (2014). This section of Appendix B provides a brief overview of sinkhole notification, investigation, stabilization, and final grading.

Monitoring of BMPs in karst regions

A water quality monitoring system installed, operated, and maintained by the owner/operator is RECOMMENDED, particularly where drinking water supplies are derived from ground water or associated with known sources of contamination. The location of monitoring wells or BMP performance monitoring will depend upon the nature of the BMP and surrounding karst characteristics. This could mean the installation of a monitoring system designed to reflect variable water behavior typical of karst water flow in addition to the monitoring of the performance of the BMP. Monitoring of groundwater and stormwater runoff behavior requires a thorough understanding of the local geology as the hydrology of karst terrains is vastly different from that of non-karst terrains (EPA, 1989).

Below is a list of resources that provide additional information on runoff and/or groundwater monitoring in karst areas.

- Ground-Water Monitoring in Karst Terranes: Recommended Protocols & Implicit Assumptions (EPA, 1989). This report provides information on the monitoring procedures and common monitoring pitfalls in karst areas. It describes where to monitor for pollutants, where to monitor for background water quality, when to monitor the groundwater, and how to do all this reliably and economically.

- Highway Stormwater Runoff in Karst Areas – Preliminary Results of Baseline Monitoring and Design of a Treatment System for a Sinkhole in Knoxville Texas (Stephenson et al., 1999). The authors of this report discuss the use of quantitative dye tracing and hydrograph analyses to monitor stormwater runoff and resulting groundwater flow from runoff from a highway system.

- Evaluating the Effectiveness of Regulatory Stormwater Monitoring Protocols on Groundwater Quality in Urbanized Karst Regions (Nedvidek, 2014). This report looks at monitoring techniques and frequencies. It also discusses how to make these monitoring programs cost effective, while still providing a sufficient amount of information.

BMP failure

In case of BMP failure in karst areas,

- if waters of the state are or may be impacted, contact the state duty officer (651-649-5451 or 800-422-0798; or 651-297-5353 TDD Line/800-627-3529 TDD Watts Line);

- contact appropriate local authorities; and/or

- repair the practice following guidance above.

Related pages

- Overview of stormwater infiltration

- Pre-treatment considerations for stormwater infiltration

- BMPs for stormwater infiltration

- Pollutant fate and transport in stormwater infiltration systems

- Surface water and groundwater quality impacts from stormwater infiltration

- Stormwater infiltration and groundwater mounding

- Stormwater infiltration and setback (separation) distances

- Karst

- Shallow soils and shallow depth to bedrock

- Shallow groundwater

- Soils with low infiltration capacity

- Potential stormwater hotspots

- Stormwater and wellhead protection

- Stormwater infiltrations and contaminated soils and groundwater

- Decision tools for stormwater infiltration

- Stormwater infiltration research needs

- References for stormwater infiltration

This page was last edited on 31 January 2023, at 15:57.