Difference between revisions of "Construction specifications for bioretention"

m |

|||

| Line 168: | Line 168: | ||

<onlyinclude>{{#ifeq:{{{transcludesection|Alleviating compaction resulting from construction}}}|Alleviating compaction resulting from construction| | <onlyinclude>{{#ifeq:{{{transcludesection|Alleviating compaction resulting from construction}}}|Alleviating compaction resulting from construction| | ||

| − | |||

Alleviation of compaction of disturbed soil is crucial to the installation of successful vegetated stormwater infiltration practices. Typical bulk densities for non-compacted soils are in the range of 1.0 to 1.50 grams per cubic centimeter. Urban soils typically have bulk densities greater than this. Construction activities can increase bulk densities by 20 percent or more. The compaction can extend up to two feet into the soil profile, often resulting in bulk densities that do not readily support healthy plant growth. | Alleviation of compaction of disturbed soil is crucial to the installation of successful vegetated stormwater infiltration practices. Typical bulk densities for non-compacted soils are in the range of 1.0 to 1.50 grams per cubic centimeter. Urban soils typically have bulk densities greater than this. Construction activities can increase bulk densities by 20 percent or more. The compaction can extend up to two feet into the soil profile, often resulting in bulk densities that do not readily support healthy plant growth. | ||

Revision as of 20:42, 21 October 2014

This page provides construction details, materials specifications and construction specifications for bioretention systems.

Contents

- 1 Construction details

- 2 Construction specifications

- 3 References

- 4 Related pages

Construction details

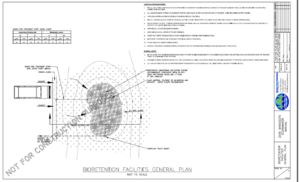

CADD based details for bioretention are contained in the Computer-aided design and drafting (CAD/CADD) drawings section. The following details, with specifications, have been created for bioretention systems:

- Bioretention Facilities General Plan

- Bioretention plan-offline NEW

- Bioretention plan-online NEW

- Biofiltration planter - Plan NEW

- Bioretention parking median - Plan NEW

- Bioretention Facilities Performance Types Cross-Sections

- Bioinfiltration NEW

- Biofiltration with underdrain at the bottom NEW

- Biofiltration with elevated underdrain NEW

- Biofiltration with internal water storage NEW

- Biofiltration with liner NEW

- Biofiltration planter - Section NEW

- Bioretention parking median - Section NEW

- Cleanout NEW

- Underdrain valve NEW

- Biofiltration with elevated underdrain NEW

- Biofiltration with internal water storage NEW

- Biofiltration with underdrain at bottom NEW

- Bioinfiltration NEW

- Biofiltration with liner NEW

- Infiltration / Recharge Facility

- Filtration / Partial Recharge Facility

- Infiltration / Filtration / Recharge Facility

- Filtration Only Facility

Construction specifications

Proper construction techniques are critical to achieve long-term functionality of bioretention systems. Construction sequencing is imperative; infiltration BMPs need to be installed as close to the end of construction as possible. Preferably, site slopes have been stabilized and the asphalt has been installed before the bioretention construction begins. However, this is not always possible in bioretention cells that are surrounded by a parking lot and are the only outlet for stormwater. In this case, excavate the bioretention cell during a period of dry weather. Install the underdrains, the outlet structure, and the media up to the proposed final elevation. Once the construction of the parking lot is complete, scrape off any silty or clayey confining layer that has accumulated on top of the media and remove it from the site and de-compact soil. Top up media to desired finished elevation. Mulch and plants (or sod if it is a grassed bioretention cell) may then be installed.

During construction it is critical to keep sediment out of the infiltration device as much as practicable. Utilizing sediment and erosion control measures, such as compost logs, check dams, and sediment basins, will help to keep bioretention cells from clogging. As soon as grading is complete, slopes should be stabilized to reduce erosion of native soils. If vegetated filter strips are used as pre-treatment, they must be vegetated as soon as possible following the completion of grading.

If the bioretention cell has sod specified for its cover (as opposed to tree/shrub/mulch systems), the sod must be either 1) grown on sandy underlying soils or 2) be washed sod. Washed sod has had all soil removed from the roots, which prevents the sod layer from restricting infiltration into the underlying media. It also typically roots more quickly than standard sod.

Preventing and alleviating compaction are crucial during construction of infiltration practices, as compaction can reduce infiltration rates in sandy soils by an order of magnitude and in clayey soils by a factor of 50 (Pitt et al. , 2008). Therefore, it is critical to keep heavy construction equipment from compacting or smearing soils at the bottom of the excavation. Excavate the soil from the perimeter of the infiltration device. Tracked vehicles should be used to reduce the pressure placed on the soil. It is highly recommended to excavate during dry conditions to prevent smearing of the soil, which has been shown to reduce the soil infiltration rate (Brown and Hunt, 2010). Driveable mats can be used for backfill and grading to minimize compaction. During the final pass with the excavator bucket (i.e. bottom of excavation), it is highly recommended to rake the soil with the teeth of the bucket to loosen any compaction (Brown and Hunt, 2010). Smooth bucket blades smear soils and restrict infiltration rates. Soil ripping has also been shown to increase infiltration and reduce compaction from construction activities (Tyner et al., 2009; Wardynski et al., 2013).

Given that the construction of bioretention practices incorporates techniques or steps which may be considered non-traditional, it is recommended that the construction specifications include the format and information discussed below.

Temporary erosion control

- It is REQUIRED that future bioretention locations not be used as temporary sedimentation basins unless 3 feet of cover is left in place during construction.

- If the bioretention area is excavated to final grade (or within 3 feet of) it is REQUIRED that rigorous erosion prevention and sediment controls (e.g. diversion berms) are used to keep sediment and runoff completetly away from the bioretention area.

- Install prior to site disturbance

- Protect catch basin/inlet

- Cover erodible surfaces, for example with plastic covers, that can be re-used.

Excavation, backfill and grading

- It is HIGHLY RECOMMENDED that prior to beginning the installation, sufficient material quantities shall be onsite to complete the installation and stabilize exposed soil areas without delay.

- It is HIGHLY RECOMMENDED that excavation, soil placement and rapid stabilization of perimeter slopes be completed before the next precipitation event

- Timing of grading of infiltration practices relative to total site development

- Use of low-impact, earth moving equipment (wide track or marsh track equipment, or light equipment with turf-type tires)

- Do not over-excavate

- Restoration in the event of sediment accumulation during construction of practice

- Alleviate any compacted soil (compaction can be alleviated at the base of the practice by using a primary tilling operation such as a chisel plow, ripper or sub-soiler to a minimum 12 inch depth

- Gravel backfill specifications

- Gravel filter specifications

- Filter fabric specifications

Alleviating compaction resulting from construction

Alleviation of compaction of disturbed soil is crucial to the installation of successful vegetated stormwater infiltration practices. Typical bulk densities for non-compacted soils are in the range of 1.0 to 1.50 grams per cubic centimeter. Urban soils typically have bulk densities greater than this. Construction activities can increase bulk densities by 20 percent or more. The compaction can extend up to two feet into the soil profile, often resulting in bulk densities that do not readily support healthy plant growth.

Comparison of bulk densities for undisturbed soils and common urban conditions. (Source: Schueler, T. 2000. The Compaction of Urban Soils: Technical Note #107 from Watershed Protection Techniques. 3(2): 661-665. Center for Watershed Protection, Ellicott City, MD.)

For information on alleviating soil compaction, see Alleviating compaction from construction activities

Link to this table

| Undisturbed soil type or urban condition | Surface bulk density (grams / cubic centimeter |

|---|---|

| Peat | 0.2 to 0.3 |

| Compost | 1.0 |

| Sandy soil | 1.1 to 1.3 |

| Silty sands | 1.4 |

| Silt | 1.3 to 1.4 |

| Silt loams | 1.2 to 1.5 |

| Organic silts / clays | 1.0 to 1.2 |

| Glacial till | 1.6 to 2.0 |

| Urban lawns | 1.5 to 1.9 |

| Crushed rock parking lot | 1.5 to 2.0 |

| Urban fill soils | 1.8 to 2.0 |

| Athletic fields | 1.8 to 2.0 |

| Rights of way and building pads (85% compaction) | 1.5 to 1.8 |

| Rights of way and building pads (95% compaction) | 1.6 to 2.1 |

| Concrete pavement | 2.2 |

| Quartzite (rock) | 2.65 |

Increase in soil bulk density as a result of different land uses or activities.

Link to this table

| Land use or activity | Increase in bulk density (grams / cubic centimeter | Source (link to Reference list) |

|---|---|---|

| Grazing | 0.12 to 0.20 | Smith, 1999 |

| Crops | 0.25 to 0.35 | Smith, 1999 |

| Construction, mass grading | 0.34 to 0.35 | Randrup, 1998; Lichter and Lindsey, 1994 |

| Construction, no grading | 0.20 | Lichter and Lindsey, 1994 |

| Construction traffic | 0.17 to 0.40 | Lichter and Lindsey, 1994; Smith, 1999; Friedman, 1998 |

| Athletic fields | 0.38 to 0.54 | Smith, 1999 |

| Urban lawn and turf | 0.30 to 0.40 | Various sources |

While natural processes can alleviate soil compaction, additional techniques to alleviate soil compaction are often desirable because

- it can take many years for natural processes to loosen up soil;

- natural processes operate primarily within the first foot or so of soil, and compaction from development can extend to two feet deep; and

- once soil compaction becomes so severe that plants and soil microbes can no longer thrive, natural processes are no longer able to reduce soil compaction.

The most effective method for alleviating compaction is to add compost amendment. Other amendments, such as sand (in clay soils), can significantly reduce compaction since sandy soils are more resistant to compaction. An additional technique for alleviating compaction is subsoiling or soil ripping, although ripping by itself appears to have limitations. Ripping is most effective when used in conjunction with compost and/or sand amendment.

Schueler (Technical Note 108) concludes that “Based on current research, it appears that the best construction techniques are only capable of preventing about a third of the expected increase in bulk density during construction.”

Reported activities that restore or decrease soil bulk density

Soil ripping

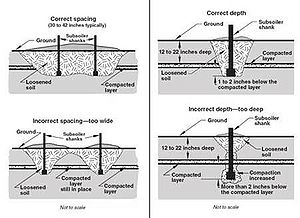

The goal of soil ripping or subsoiling is to fracture compacted soil without adversely disturbing plant life, topsoil, and surface residue. Soil compaction occurs most frequently with soils having a high clay content. Fracturing compacted soil promotes root penetration by reducing soil density and strength, improving moisture infiltration and retention, and increasing air spaces in the soil. Compacted layers typically develop 12 to 22 inches below the surface when heavy equipment is used. Conventional cultivators cannot reach deep enough to break up this compaction. Subsoilers (rippers) can break up the compacted layer without destroying soil aggregate structure, surface vegetation, or mixing soil layers (Kees, 2008).

How effectively compacted layers are fractured depends on the soil's moisture, structure, texture, type, composition, porosity, density, and clay content. Success depends on the type of equipment selected, its configuration, and the speed with which it is pulled through the ground. No one piece of equipment or configuration works best for all situations and soil conditions, making it difficult to define exact specifications for subsoiling equipment and operation.

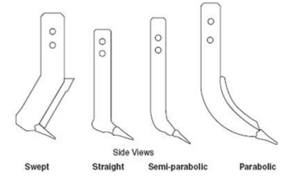

Subsoilers are available with a wide variety of shank designs. Shank design affects subsoiler performance, shank strength, surface and residue disturbance, effectiveness in fracturing soil, and the horsepower required to pull the subsoiler. According to Kees (2008), “Parabolic shanks require the least amount of horsepower to pull. In some forest applications, parabolic shanks may lift too many stumps and rocks, disturb surface materials, or expose excess subsoil. Swept shanks tend to push materials into the soil and sever them. They may help keep the subsoiler from plugging up, especially in brush, stumps, and slash. Straight or "L" shaped shanks have characteristics that fall somewhere between those of the parabolic and swept shanks.”

Researchers have found that there is a “critical depth”, and according to Spoor and Godwin (1978) this “critical depth is dependent upon the width, inclination and lift height of the tine foot and on the moisture and density status of the soil.” Spoor and Godwin (1978) explainthat tine depth is crucial because “At shallow working depths the soil is displaced forwards, side-ways and upwards (crescent failure), failing along well defined rupture planes which radiate from just above the tine tip to the surface at angles of approximately 45” to the horizontal. Crescent failure continues with increasing working depth until, at a certain depth, the critical depth, the soil at the tine base begins to flow forwards and sideways only (lateral failure) creating compaction at depth.” They found that below the critical depth “compaction occurs rather than effective soil loosening.” They also found that “The wetter and more plastic a soil is, the shallower is thecritical depth.” An approach developed by Silsoe College, Cranfield University, in collaboration with Transco UK, for use on pipeline sites, was to work progressively deeper with repeated passes, up to 5 or 6 under extreme conditions, with the tractor operating on the same tramline/traffic lane on each pass (Spoor & Foot, 1998).”

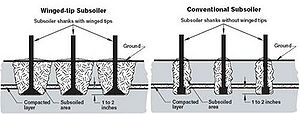

Shanks are available with winged tips and conventional tips. Winged tips cost more than conventional tips and require more horsepower, but can often be spaced farther apart. Increasing wing width also increases critical depth – the depth below which little soil loosening occurs (Owen 1987, Spoor 1978). Using shallow leading tines ahead of deeper tines also increases required shank spacing (Spoor 1978). According to Kees (2008), the shank’s tip should run to a depth of 1 to 2 inches below the compacted layer. Kees (2008) also recommends making sure that the shanks on the subsoiler are spaced so that they run in the tracks of the tow vehicle, because the equipment used to pull subsoilers is heavy enough to create compaction itself. Ideal shank spacing will depend on soil moisture, soil type,degree of compaction, and the depth of the compacted layer. Spacing should be adjustable so the worked area can be fractured most efficiently. Because ideal shank configuration will vary with varying soil textures and moisture, shank spacing and height should be adjustable in the field (Kees 2008).

Kees (2008) recommends following ground contours whenever possible when subsoiling to “increase water capture, protect water quality, and reduce soil erosion.” He also states that “in some cases, two passes at an angle to each other may be required to completely fracture compacted soil.” Spoor and Godwin (1978) also found that “Relatively closely spaced tines, staggered to prevent blockage, are more efficient at producing complete loosening than repeated passes with tines at wider spacings.”

Travel speed of the subsoiler also affects subsoiling disturbance. “Travel speed that is too high can cause excessive surface disturbance, bring subsoil materials to the surface, create furrows, and bury surface residues. Travel speed that is too slow may not lift and fracture the soil adequately” (Kees2008).

Soils should be mostly dry and friable. Urban (2008) describes ideal conditions for compaction reduction as follows: “soil moisture must be between field capacity and wilt point during compaction reduction for maximum effectiveness.

Always know where utilities are buried prior to subsoiling. Avoid subsoiling in area that have buried utilities, wires, pipes, culverts, or diversion channels (Kees 2008, Urban 2008).

Soil ripping will generally be more effective with the addition of an amendment. This can be either sand or compost. Tilling in compost amendment may not be desirable on sites with steep slopes, a high water table, wet saturated soils, or downhill slope toward a house foundation (Schueler Technical Note #108) or where there are tree roots or utilities, or where nutrients leaching from compost would pose a problem. Since soil restoration techniques will need to be tailored to site conditions, a prescriptive soil restoration specification is not recommended. However, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Washington State have specifications for soil amendment and restoration and these may be used as guidance in determining how to amend a compacted soil.

According to Spoor and Godwin (1978) “The number of variables involved and soil variation make the accurate prediction of the critical depth for field conditions impractical. Simple field modifications are available, however, such as increasing tine foot width and lift height or loosening the surface layers, to allow rapid implement adjustment to satisfy a range of field conditions.” If subsoiling was effective, “The ground should be lifted slightly and remain relatively even behind the subsoiler, without major disruption of surface residues and plants. No more than a little subsoil and a few rocks should be pulled to the surface. If large furrows form behind the subsoiler, the shanks may not be deep enough, the angle on winged tips may be too aggressive, or the travel speed may be too high” (Kees 2008).

Cost for subsoiling varies by project. The Pennsylvania Stormwater Best Management Practices Manual estimates the cost of tilling soils ranges from $800 to $1000 per acre, while the cost of compost amending soil is about the same.

An extensive literature review of the effects of soil ripping can be found in File:Bioretention task 6 soil ripping.docx.

Recommendations for soil ripping to alleviate compaction

For basins larger than 1000 square feet, if compaction is above ideal bulk density indicated in the table below the soil should be remediated as follows:

- Rip to a depth of 18 inches where feasible

- For clay subsoil, incorporate 2 inches of sand. For bioretention without an underdrain, MnDOT Type 2 compost may be incorporated instead of sand.

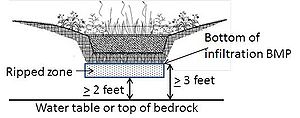

- Maintain a 3 foot minimum separation distance between the bottom of the infiltration practice and the seasonally high water table or bedrock. If soil ripping is utilized, the requirement is a 2 foot minimum between the bottom of the ripped zone and a 3 foot minimum from the bottom of the infiltration practice to the water table or top of bedrock. If there is only a 3 foot separation distance between the bottom of the infiltration practice and the elevation of the seasonally high water table or bedrock, limit ripping depth to 1 foot (12 inches).

General relationship of soil bulk density to root growth based on soil texture

Link to this table

| Soil texture | Ideal bulk densities (g/cm3) | Bulk densities that may affect plantgrowth (g/cm3) | Bulk densities that restrict root growth (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| sands, loamy sands | <1.60 | 1.69 | >1.80 |

| sandy loams, loams | <1.40 | 1.63 | >1.80 |

| sandy clay loams, loams, clay loams | <1.40 | 1.60 | >1.75 |

| silts, silt loams | <1.30 | 1.60 | >1.75 |

| silt loams, silty clay loams | <1.40 | 1.55 | >1.65 |

| sandy clays, silty clays, clay loams with 35-45% clay | <1.10 | 1.49 | >1.58 |

| clays (>45% clay) | <1.10 | 1.39 | >1.47 |

Effect of ripping plus compost amendment on soil compaction

Compost aggregates soil particles (sand, silt, and clay) into larger particles (Cogger, 2005). Aggregation of soil particles creates additional porosity, which reduces the bulk density of the soil (Cogger, 2005). Compost can also reduce the bulk density of a soil by dilution of the mineral matter in the soil (Cogger, 2005). When the porosity of the soil increases and the particle surface area increases, water holding capacity is also increased (Cogger, 2005). Increases in macropore continuity have been found as well (Harrison et al., 1998). Studies have cited numerous beneficial abilities of compost: increased water drainage, increased water holding capacity, increased plant production, increased root penetrability, reduction of soil diseases, reduction of heavy metals, and the ability to treat many chemical pollutants (EPA, 1997; Harrison et al., 1998; WDOE Stormwater Management Manual, 2007; Olson 2010).

Studies show that tilling in compost is an effective technique to alleviate soil compaction. Two of these studies are summarized below.

- Olson (2010) found that plots where soil was ripped and amended with compost showed reduced soil strength, bulk densities were 18 to 37 percent lower on compost plots compared to controls, and the geometric mean of Ksat on the compost plots was 2.7 to 5.7 times that of the control plot.

- A study at Virginia Tech shows soils with compost incorporated into the soil to a depth of 2 feet has decreased bulk density in the subsoil and is accelerating the process of soil formation and long-term carbon storage compared to other treatments in the study. The result is that trees growing in the compost-amended soil have increased height, canopy diameter, and trunk diameter compred to trees in other treatments.

Precedents for soil restoration specifications

Since soil restoration techniques will need to be tailored to site conditions, a prescriptive soil restoration specification is not recommended. The 2006 Pennsylvania Stormwater Best Management Practices Manual’s chapter on soil amendment and restoration provides a sample specification for soil restoration. Their specification is not prescriptive, but does provide guiding principles, compost material specifications, and performance requirements. They require sub-soiling to loosen soil to less than 1400 kPa (200 psi) to a depth of 20 inches below final topsoil grade to reduce soil compaction in all areas where plant establishment is planned in areas where subsoil has become compacted by equipment operation, or has become dried out andcrusted, or where necessary to obliterate erosion hills.

The Virginia Tech Rehabilitation study website also provides a Soil Profile Rebuilding Specification based on their research. The basic steps in their specification are described below.

- Spread mature, stable compost to a 4 inch depth over compacted subsoil.

- Subsoil to a depth of 24 inches.

- Replace topsoil to 4 inches (6 to 8 inches if severely disturbed).

- Rototill topsoil to a depth of 6 to 8 inches.

- Plant with woody plants.

Washington State’s Department of Ecology’s Stormwater Management for Western Washington (Volume V: Runoff Treatment BMPs, Chapter 5, pages 5-7 to 5-10) also includes a very detailed soil restoration specification that includes the following.

- The topsoil layer has a minimum organic matter content of 10 percent dry weight in planting beds, 5 percent organic matter content in turf areas, and a pH from 6.0 to 8.0 or matching the pH of the undisturbed soil. The topsoil layer shall have a minimum depth of 8 inches except where tree roots limit the depth of incorporation of amendments needed to meet the criteria. Subsoils below the topsoil layer should be scarified at least 4 inches with some incorporation of the upper material to avoid stratified layers, where feasible.

- Mulch planting beds with 2 inches of organic material.

- Use compost and other materials that meet these organic content requirements.

- The organic content for pre-approved amendment rates can be met only using compost that meets the definition of composted materials in WAC 173-350-100. The compost must also have an organic matter content of 40 to 65 percent and a carbon to nitrogen ratio below 25:1. The carbon to nitrogen ratio may be as high as 35:1 for plantings composed entirely of plants native to the Puget Sound Lowlands region.

- Calculated amendment rates may be met through use of composted materials meeting above conditions, or other organic materials amended to meet the carbon to nitrogen ratio requirements and meeting the contaminant standards of Grade A Compost. The resulting soil should be conducive to the type of vegetation to be established.

- The soil quality design guidelines listed above can be met by using one of the methods listed below.

- Leave undisturbed native vegetation and soil, and protect from compaction during construction.

- Amend existing site topsoil or subsoil either at default pre-approved rates, or at custom calculated rates based on tests of the soil and amendment.

- Stockpile existing topsoil during grading, and replace it prior to planting. Stockpiled topsoil must also be amended if needed to meet the organic matter or depth requirements, either at a default pre-approved rate or at a custom calculated rate.

- Import topsoil mix of sufficient organic content and depth to meet the requirements. More than one method may be used on different portions of the same site. Soil that already meets the depth and organic matter quality standards, and is not compacted, does not need to be amended.

Native plants, planting and transplanting

Native plants, planting and transplanting

Vigorous plants are crucial to the bioretention system’s long term stormwater performance. Plant roots help soil particles form stable aggregates, improve soil structure, maintain and increase water storage and infiltration capacity, as well as improve stormwater pollutant removal. Specific stormwater benefits include the following.

- Crucial to Long Term Infiltration: As plant roots grow and then decay, they restore and/or enhance soil porosity and infiltration rates. Deeper rooted plants yield higher infiltration rates than shallow rooted plants. Bioretention practices with native prairie plants will typically have greater infiltration rates, deeper rooting depths, greater biological activity of flora and fauna, and deeper drainage compared to turf systems.

- Crucial to Water Quality Benefits: Plants in bioretention systems have been shown to improve dissolved nutrient removal, improve hydrocarbon removal and aid TSS sequestration.

- Interception and Evapotranspiration: Woody vegetation typically intercepts and evapotranspires significantly more water than herbaceous vegetation, and large trees intercept and evapotranspire significantly more rain than small trees

Construction considerations include the following.

- timing of native seeding and native planting;

- weed control; and

- watering of plant material.

Construction sequence scheduling

- Temporary construction access

- Location of temporary sediment and erosion control practices to protect BMPs and downstream receiving waters

- Removal and storage of excavated material

- Installation of underground utilities

- Rough grading

- Seeding and mulching disturbed areas

- Road construction

- Final grading

- Site stabilization

- Installation of semi-permanent and permanent erosion control measures

- Removal of temporary sediment and erosion control devices

Construction observation

- Adherence to construction documents

- Verification of physical site conditions

- Erosion control measures installed appropriately

References

- Brown, R.A. and Hunt, W.F. (2010). Impacts of construction activity on bioretention performance. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering. 15(6), 386-394.

- Chaplin, Jonathan, Min Min, and Reid Pulley. 2008. Compaction Remediation for Construction Sites. Final Report. Department of Bioproducts and Biosystems Engineering, University of Minnesota, St. Paul,Minnesota.

- Cogger, C. 2005. Potential Compost Benefits for Restoration of Soils Disturbed by Urban Development. Compost Science & Utilization. 13.4:243-251.

- Hanks, Dallas, and A. Lewandowski, 2003. Protecting Urban Soil Quality: Examples for Landscape Codes and Specifications. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Services.

- Kees, Gary. 2008. Using Subsoiling To Reduce Soil Compaction. U.S. Forest Service Technology & Development Publication 3400 Forest Health Protection 0834-2828-MTDC.

- NRCS. 1998. Soil Quality Test Kit Guide.

- Olson, Nicholas Charles. 2010. Quantifying the Effectiveness of Soil Remediation Techniques in Compact Urban Soils. University Of Minnesota Master Of Science Thesis.

- Owen, Gordon T. 1987. Soil disturbance associated with deep subsoiling in compact soils. Canadian Agricultural Engineering: 33-37.

- Pennsylvania department of Environmental Protection. 2006. Pennsylvania Stormwater Best Management Practices Manual. BMP 6.7.3: Soil Amendment & Restoration. 2006.

- Pitt, R., Chen, S., Clark, S.E., Swenson, J., and Ong, C.K. 2008. Compaction’s impact on urban storm-water infiltration. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering. 134(5):652-658.

- Schueler, T. 2000. The Compaction of Urban Soil: The Practice of Watershed Protection. Center for Watershed Protection, Ellicott City, MD. pp. 210-214.

- Schueler, T. R. Can Urban Soil Compaction Be Reversed? Technical Note #108 from Watershed Protection Techniques. 1(4): 666-669.

- Selbig, W.R., and N. Balster. 2010. Evaluation of turf-grass and prairie-vegetated rain gardens in a clay and sand soil: Madison, Wisconsin, water years 2004–08. U.S. Geological Survey, Scientific Investigation Report 2010–5077, 75 p.

- Spoor, G. & Godwin, R.J. 1978. An experimental investigation into the deep loosening of soil by rigid tines. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research, 23, 243–258.

- Spoor, G., Tijink, F.G.J. & Weisskopf, P. 2003. Subsoil compaction: risk, avoidance, identification and alleviation. Soil and Tillage Research,73, 175–182.

- Spoor, G. 2006. Alleviation of Soil Compaction: Requirements, Equipment and Techniques. Soil Use and Management 22:113-122.

Related pages

- Bioretention terminology (including types of bioretention)

- Overview for bioretention

- Design criteria for bioretention

- Construction specifications for bioretention

- Operation and maintenance of bioretention

- Cost-benefit considerations for bioretention

- Soil amendments to enhance phosphorus sorption

- Summary of permit requirements for bioretention

- Supporting material for bioretention

- External resources for bioretention

- References for bioretention

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using bioretention with no underdrain BMPs in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using bioretention with an underdrain BMPs in the MIDS calculator