Difference between revisions of "Calculating credits for tree trenches and tree boxes"

m |

m |

||

| (49 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="float:right; margin-left: 10px; width:100px;" | {| class="wikitable" style="float:right; margin-left: 10px; width:100px;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 15: | Line 13: | ||

|'''Hydrocarbons''' | |'''Hydrocarbons''' | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | 80 |

| [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Phosphorus_credits_for_bioretention_systems_with_an_underdrain link to table] | | [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Phosphorus_credits_for_bioretention_systems_with_an_underdrain link to table] | ||

| [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Phosphorus_credits_for_bioretention_systems_with_an_underdrain link to table] | | [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Phosphorus_credits_for_bioretention_systems_with_an_underdrain link to table] | ||

| Line 25: | Line 23: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | [[File:Pdf image.png|100px|thumb|left|alt=pdf image|<font size=3>[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=File:Calculating_credits_for_tree_trenches_and_tree_boxes_-_Minnesota_Stormwater_Manual_May_2022.pdf Download pdf]</font size>]] | ||

| + | [[File:Summary image.jpg|100px|left|thumb|alt=image|<font size=3>[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=File:Credit_page_descriptions.mp4 Page video summary]</font size>]] | ||

| + | [[File:Technical information page image.png|100px|left|alt=image]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{alert|Models are often selected to calculate credits. The model selected depends on your objectives. For compliance with the Construction Stormwater permit, the model must be based on the assumption that an instantaneous volume is captured by the BMP.|alert-danger}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[file:Check it out.png|200px|thumb|alt=image|<font size=3> | ||

| + | *The tree interception credit has been updated. [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=File:Tree_Performance_Memo.docx See the technical memo]</font size>]] | ||

| − | [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Overview_of_stormwater_credits Credit] refers to the quantity of stormwater or pollutant reduction achieved | + | {{alert|Trees can be an important tool for retention and detention of stormwater runoff. Trees provide additional benefits, including cleaner air, reduction of heat island effects, carbon sequestration, reduced noise pollution, reduced pavement maintenance needs, and cooler cars in shaded parking lots.|alert-success}} |

| + | |||

| + | [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Overview_of_stormwater_credits Credit] refers to the quantity of stormwater or pollutant reduction achieved either by an individual <span title="One of many different structural or non–structural methods used to treat runoff"> '''best management practice'''</span> (BMP) or cumulatively with multiple BMPs. Stormwater credits are a tool for local stormwater authorities who are interested in | ||

*providing incentives to site developers to encourage the [[Credits for Better Site design|preservation of natural areas and the reduction of the volume of stormwater]] runoff being conveyed to a best management practice (BMP); | *providing incentives to site developers to encourage the [[Credits for Better Site design|preservation of natural areas and the reduction of the volume of stormwater]] runoff being conveyed to a best management practice (BMP); | ||

| − | *complying with permit requirements, including antidegradation (see [ | + | *complying with permit requirements, including antidegradation (see [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Construction_stormwater_program Construction permit]; [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Stormwater_Program_for_Municipal_Separate_Storm_Sewer_Systems_(MS4) Municipal (MS4) permit]); |

*meeting the [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Performance_goals_for_new_development,_re-development_and_linear_projects MIDS performance goal]; or | *meeting the [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Performance_goals_for_new_development,_re-development_and_linear_projects MIDS performance goal]; or | ||

| − | *meeting or complying with water quality objectives, including [ | + | *meeting or complying with water quality objectives, including <span title="The amount of a pollutant from both point and nonpoint sources that a waterbody can receive and still meet water quality standards"> [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Total_Maximum_Daily_Loads_(TMDLs) '''total maximum daily load''']</span> (TMDL) <span title="The portion of a receiving water's assimilative capacity that is allocated to one of its existing or future point sources of pollution"> '''wasteload allocations'''</span> (WLAs). |

This page provides a discussion of how tree trench/tree box practices can achieve stormwater credits. [[Trees|Tree systems]] with and without [[Glossary#U|underdrains]] are both discussed, with separate sections for each type of system as appropriate. | This page provides a discussion of how tree trench/tree box practices can achieve stormwater credits. [[Trees|Tree systems]] with and without [[Glossary#U|underdrains]] are both discussed, with separate sections for each type of system as appropriate. | ||

==Overview== | ==Overview== | ||

| − | Tree trenches and tree boxes are specialized | + | Tree trenches and tree boxes are specialized <span title="Bioretention is a terrestrial-based (up-land as opposed to wetland) water quality and water quantity control process. Bioretention employs a simplistic, site-integrated design that provides opportunity for runoff infiltration, filtration, storage, and water uptake by vegetation. Bioretention areas are suitable stormwater treatment practices for all land uses, as long as the contributing drainage area is appropriate for the size of the facility. Common bioretention opportunities include landscaping islands, cul-de-sacs, parking lot margins, commercial setbacks, open space, rooftop drainage and street-scapes (i.e., between the curb and sidewalk). Bioretention, when designed with an underdrain and liner, is also a good design option for treating Potential stormwater hotspots. Bioretention is extremely versatile because of its ability to be incorporated into landscaped areas. The versatility of the practice also allows for bioretention areas to be frequently employed as stormwater retrofits."> '''bioretention practices'''</span> practices. They are therefore terrestrial-based (up-land as opposed to wetland) water quality and water quantity control process. Tree systems consist of an <span title="Engineered media is a mixture of sand, fines (silt, clay), and organic matter utilized in stormwater practices, most frequently in bioretention practices. The media is typically designed to have a rapid infiltration rate, attenuate pollutants, and allow for plant growth."> [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Design_criteria_for_bioretention#Materials_specifications_-_filter_media '''engineered soil media''']</span> designed to treat stormwater runoff via <span title="Filtration Best Management Practices (BMPs) treat urban stormwater runoff as it flows through a filtering medium, such as sand or an organic material. They are generally used on small drainage areas (5 acres or less) and are primarily designed for pollutant removal. They are effective at removing total suspended solids (TSS), particulate phosphorus, metals, and most organics. They are less effective for soluble pollutants such as dissolved phosphorus, chloride, and nitrate."> [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Filtration '''filtration''']</span> through plant and soil media, <span title="Loss of water to the atmosphere as a result of the joint processes of evaporation and transpiration through vegetation"> '''evapotranspiration'''</span> from trees, or through <span title="Infiltration Best Management Practices (BMPs) treat urban stormwater runoff as it flows through a filtering medium and into underlying soil, where it may eventually percolate into groundwater. The filtering media is typically coarse-textured and may contain organic material, as in the case of bioinfiltration BMPs."> [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Stormwater_infiltration_Best_Management_Practices '''infiltration''']</span> into underlying soil. *<span title="Pretreatment reduces maintenance and prolongs the lifespan of structural stormwater BMPs by removing trash, debris, organic materials, coarse sediments, and associated pollutants prior to entering structural stormwater BMPs. Implementing pretreatment devices also improves aesthetics by capturing debris in focused or hidden areas. Pretreatment practices include settling devices, screens, and pretreatment vegetated filter strips."> [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Pretreatment '''Pretreatment''']</span> is REQUIRED for all bioretention facilities, including tree-based systems, to settle particulates before entering the BMP. Tree practices may be built with or without an <span title="An underground drain or trench with openings through which the water may percolate from the soil or ground above"> '''underdrain'''</span>. Other common components may include a stone aggregate layer to allow for increased retention storage and an <span title="Impermeable means not allowing something, such as water, to pass through. Some materials considered impermeable may actually allow water to pass through at very slow rates, such as 10(-8) cm/sec."> '''impermeable'''</span> liner on the bottom or sides of the facility if located near buildings, subgrade utilities, or in <span title="Karst is a landscape formed by the dissolution of a layer or layers of soluble bedrock. The bedrock is usually carbonate rock such as limestone or dolomite but the dissolution has also been documented in weathering resistant rock, such as quartz. The dissolution of the rocks occurs due to the reaction of the rock with acidic water. Rainfall is already slightly acidic due to the absorption of carbon dioxide (CO2), and becomes more so as it passes through the subsurface and picks up even more CO2. Cracks and fissures form as the runoff passes through the subsurface and reacts with the rocks. These cracks and fissures grow, creating larger passages, caves, and may even form sinkholes as more and more acidic water infiltrates into the subsurface."> [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Karst '''Karst''']</span> formations. |

===Pollutant removal mechanisms=== | ===Pollutant removal mechanisms=== | ||

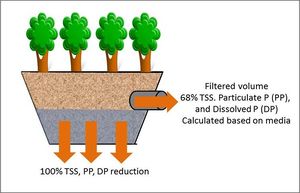

[[File:Schematic of pollutant reductions tree trench with underdrain.jpg|300px|thumb|alt=schematic of pollutant reductions from tree trench with an underdrain BMP|<font size=3>Schematic illustrating how pollutant reductions (TSS, dissolved and particulate P) are calculated for a tree trench system-tree box.</font size>]] | [[File:Schematic of pollutant reductions tree trench with underdrain.jpg|300px|thumb|alt=schematic of pollutant reductions from tree trench with an underdrain BMP|<font size=3>Schematic illustrating how pollutant reductions (TSS, dissolved and particulate P) are calculated for a tree trench system-tree box.</font size>]] | ||

| − | Like other bioretention practices, tree trenches and tree boxes have high nutrient and pollutant removal efficiencies ( | + | Like other bioretention practices, tree trenches and tree boxes have high nutrient and pollutant removal efficiencies (Mid-America Regional Council and American Public Works Association Manual of Best Management Practice BMPs for Stormwater Quality, 2012). Tree practices provide pollutant removal and volume reduction through filtration, evaporation, infiltration, transpiration, biological and microbiological uptake, and soil adsorption; the extent of these benefits is highly dependent on site specific conditions and design. In addition to phosphorus and total suspended solids (TSS), which are discussed in greater detail below, tree practices treat a wide variety of [[Calculating credits for tree trenches and tree boxes#Other pollutants|other pollutants]]. |

Removal of phosphorus is dependent on the [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Design_criteria_for_bioretention#Materials_specifications_-_filter_media engineered media]. Media mixes with high organic matter content typically leach phosphorus and can therefore contribute to water quality degradation. The Manual provides a detailed discussion of [[Design criteria for bioretention#Materials specifications - filter media|media mixes]], including information on phosphorus retention. | Removal of phosphorus is dependent on the [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Design_criteria_for_bioretention#Materials_specifications_-_filter_media engineered media]. Media mixes with high organic matter content typically leach phosphorus and can therefore contribute to water quality degradation. The Manual provides a detailed discussion of [[Design criteria for bioretention#Materials specifications - filter media|media mixes]], including information on phosphorus retention. | ||

===Location in the treatment train=== | ===Location in the treatment train=== | ||

| − | [ | + | Stormwater <span title="Multiple BMPs that work together to remove pollutants utilizing combinations of hydraulic, physical, biological, and chemical methods"> [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Using_the_treatment_train_approach_to_BMP_selection '''treatment trains''']</span> are multiple <span title="One of many different structural or non–structural methods used to treat runoff"> '''best management practices'''</span> (BMPs) that work together to minimize the volume of stormwater runoff, remove pollutants, and reduce the rate of stormwater runoff being discharged to Minnesota wetlands, lakes and streams. Tree trenches and tree boxes can be incorporated anywhere in the stormwater treatment train but are most often located in upland areas of the treatment train. The strategic distribution of tree BMPs help control runoff close to the source where it is generated. |

==Methodology for calculating credits== | ==Methodology for calculating credits== | ||

| Line 54: | Line 62: | ||

In developing the credit calculations, it is assumed the tree practice is properly designed, constructed, and maintained in accordance with the Minnesota Stormwater Manual. If any of these assumptions is not valid, the BMP may not qualify for credits or credits should be reduced based on reduced ability of the BMP to achieve volume or pollutant reductions. For guidance on design, construction, and maintenance, see the appropriate article within the [[Trees|tree]] section of the Manual. | In developing the credit calculations, it is assumed the tree practice is properly designed, constructed, and maintained in accordance with the Minnesota Stormwater Manual. If any of these assumptions is not valid, the BMP may not qualify for credits or credits should be reduced based on reduced ability of the BMP to achieve volume or pollutant reductions. For guidance on design, construction, and maintenance, see the appropriate article within the [[Trees|tree]] section of the Manual. | ||

| − | {{alert| | + | {{alert|Pretreatment is required for all filtration and infiltration practices|alert-danger}} |

| − | In the following discussion, the water | + | In the following discussion, the <span title="The volume of water that is treated by a BMP."> [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Water_quality_criteria '''Water Quality Volume''']</span> (V<sub>WQ</sub>) is delivered as an <span title="The maximum volume of water that can be retained by a stormwater practice (bmp) if the water was instantaneously added to the practice. It equals the depth of the practice times the average area of the practice. For some bmps (e.g. bioretention, infiltration trenches and basins, swales with check dams), the volume is the water stored or retained above the media, while for other practices (e.g. permeable pavement, tree trenches) the volume is the water stored or retained within the media."> '''instantaneous volume'''</span> to the BMP. The V<sub>WQ</sub> is stored within the filter media. The V<sub>WQ</sub> can vary depending on the stormwater management objective(s). For construction stormwater, V<sub>WQ</sub> is 1 inch times the new impervious surface area. For [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Minimal_Impact_Design_Standards MIDS], V<sub>WQ</sub> is 1.1 inches times the impervious surface area. |

===Volume credit calculations - no underdrain=== | ===Volume credit calculations - no underdrain=== | ||

| − | Volume credits are calculated based on the capacity of the BMP and its ability to permanently remove stormwater runoff via infiltration into the underlying soil, evapotranspiration (ET) from trees, and interception of rainfall by the tree canopy. The total volume credit, V in cubic feet, is given by | + | Volume credits are calculated based on the capacity of the BMP and its ability to permanently remove stormwater runoff via infiltration into the underlying soil, evapotranspiration (ET) from trees, and <span title="Interception refers to precipitation that does not reach the soil, but is instead intercepted by the leaves, branches of plants and the forest floor"> '''interception'''</span> of rainfall by the tree canopy. The total volume credit, V in cubic feet, is given by |

<math> V = V_{inf_b}\ + V_{ET}\ + V_I </math> | <math> V = V_{inf_b}\ + V_{ET}\ + V_I </math> | ||

| Line 69: | Line 77: | ||

====Interception credit==== | ====Interception credit==== | ||

| − | Water intercepted by a tree canopy may evaporate or be slowly released such that it does not contribute to stormwater runoff. An interception credit is given by a simplified value of the interception capacity (I<sub>c</sub> | + | Water intercepted by a tree canopy may evaporate or be slowly released such that it does not contribute to stormwater runoff. An interception credit is given by a simplified value of the interception capacity (I<sub>c</sub>) for deciduous and coniferous tree species [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=File:Tree_Performance_Memo.docx]. |

| − | *I<sub>c coniferous</sub> = 0. | + | *I<sub>c coniferous</sub> = 0.40 inches (2.2 millimeters) |

| − | *I<sub>c deciduous</sub> = 0. | + | *I<sub>c deciduous</sub> = 0.14 inches (1.1 millimeters) |

| + | |||

| + | These values intercept approximately 30% and 57% of annual rainfall over the canopy area. | ||

This credit is per storm event. | This credit is per storm event. | ||

====Infiltration and ET credits==== | ====Infiltration and ET credits==== | ||

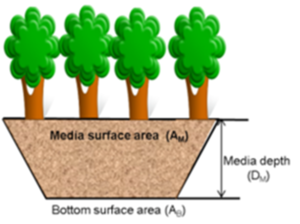

| − | [[File:Tree schematic for credits.png|300px|thumb|alt=schematic showing terms used for credit calculations for tree trench|<font size=3>Schematic illustrating terms used for calculating credits for a tree trench system.</font size>]] | + | [[File:Tree schematic for credits.png|300px|thumb|alt=schematic showing terms used for credit calculations for tree trench|<font size=3>Schematic illustrating terms used for calculating credits for a tree trench system. In calculating the credit for evapotranspiration, use the rooting depth as the depth of media. This would equal the thickness of engineered media and the depth of soil below the engineered media into which tree roots can extend.</font size>]] |

| − | The infiltration and ET credits are assumed to be instantaneous values entirely based on the capacity of the BMP to capture, store, and transmit water in any storm event. Because the volume is calculated as an instantaneous volume, the water quality volume (V<sub>WQ</sub>) is assumed to be instantly stored in the bioretention media. The volume of water between saturation and field capacity is assumed to infiltrate through the bottom of the BMP. The volume credit (V<sub>inf<sub>b</sub></sub>) for infiltration through the bottom of the BMP into the underlying soil, in cubic feet, is given by | + | {{alert|In calculating the credit for evapotranspiration, use the rooting depth as the depth of media. This would equal the thickness of engineered media and the depth of soil below the engineered media into which tree roots can extend.|alert-info}} |

| + | |||

| + | The infiltration and evapotranspiration (ET) credits are assumed to be instantaneous values entirely based on the capacity of the BMP to capture, store, and transmit water in any storm event. Because the volume is calculated as an instantaneous volume, the water quality volume (V<sub>WQ</sub>) is assumed to be instantly stored in the bioretention media. The volume of water between saturation and <span title="Field capacity is the amount of soil moisture or water content held in soil after excess water has drained away and the rate of downward movement has materially decreased, which usually takes place within 2–3 days after a rain or irrigation in pervious soils of uniform structure and texture."> '''field capacity'''</span> is assumed to infiltrate through the bottom of the BMP. The volume credit (V<sub>inf<sub>b</sub></sub>) for infiltration through the bottom of the BMP into the underlying soil, in cubic feet, is given by | ||

<math> V_{inf_b} = (n-FC)\ D_M\ (A_M + A_B)\ / 2 </math> | <math> V_{inf_b} = (n-FC)\ D_M\ (A_M + A_B)\ / 2 </math> | ||

where | where | ||

| − | :n is the porosity of the media in cubic feet per cubic foot; | + | :n is the <span title="Porosity or void fraction is a measure of the void (i.e. empty) spaces in a material, and is a fraction of the volume of voids over the total volume, between 0 and 1, or as a percentage between 0% and 100%."> '''porosity (f)'''</span> of the media in cubic feet per cubic foot; |

:FC is the field capacity of the media in cubic feet per cubic foot; | :FC is the field capacity of the media in cubic feet per cubic foot; | ||

:A<sub>M</sub> is the area at the surface of the media, in square feet; | :A<sub>M</sub> is the area at the surface of the media, in square feet; | ||

:A<sub>B</sub> is the area at the bottom of the media, in square feet; and | :A<sub>B</sub> is the area at the bottom of the media, in square feet; and | ||

| − | :D<sub>M</sub> is the media depth within the BMP, in feet. | + | :D<sub>M</sub> is the media depth within the BMP, in feet. '''In calculating the credit for evapotranspiration, use the rooting depth as the depth of media. This would equal the thickness of engineered media and the depth of soil below the engineered media into which tree roots can extend.''' |

| − | V<sub>inf<sub>b</sub></sub> should be calculated to infiltrate within a specific drawdown time. The [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Construction_stormwater_permit construction stormwater permit] has a 48 hour drawdown requirement (24 hours is recommended for discharges to trout streams). | + | V<sub>inf<sub>b</sub></sub> should be calculated to infiltrate within a specific <span title="The length of time, usually expressed in hours, for ponded water in a stormwater practice to drain. For stormwater practices where water is stored in media, there is no clear definition of drawdown, but an acceptable assumption is the time for water to drain to field capacity"> '''drawdown time'''</span>. The [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Construction_stormwater_permit construction stormwater permit] has a 48 hour drawdown requirement (24 hours is recommended for discharges to trout streams). |

| − | ET is calculated as the volume of water between field capacity and the permanent wilting point. Two calculations are needed to determine the evapotranspiration (ET) credit. The smaller of the two calculated values will be used as the ET credit. | + | ET is calculated as the volume of water between field capacity and the permanent <span title="The wilting point, also called the permanent wilting point, may be defined as the amount of water per unit weight or per unit soil bulk volume in the soil, expressed in percent, that is held so tightly by the soil matrix that roots cannot absorb this water and a plant will wilt."> '''wilting point'''. Two calculations are needed to determine the evapotranspiration (ET) credit. The smaller of the two calculated values will be used as the ET credit. |

The first calculation is the volume of water available for ET. This equals the water stored between field capacity and the wilting point. Note this calculation is made for the entire thickness of the media. | The first calculation is the volume of water available for ET. This equals the water stored between field capacity and the wilting point. Note this calculation is made for the entire thickness of the media. | ||

| − | The second calculation is the theoretical ET. The theoretical volume of ET lost ( | + | The second calculation is the theoretical ET. The theoretical volume of ET lost (Lindsey and Bassuk, 1991) per day per tree is given by |

<math>ET = (CP) (LAI) (E_{rate}) (E_{ratio})*3</math> | <math>ET = (CP) (LAI) (E_{rate}) (E_{ratio})*3</math> | ||

| − | Where: | + | Where (see definitions below): |

:CP is the canopy projection area (square feet); | :CP is the canopy projection area (square feet); | ||

:LAI is the Leaf Area Index; | :LAI is the Leaf Area Index; | ||

| Line 109: | Line 121: | ||

{{alert|The theoretical ET must be adjusted if the actual soil volume is less than the recommended volume. See the adjustment calculation below.|alert-warning}} | {{alert|The theoretical ET must be adjusted if the actual soil volume is less than the recommended volume. See the adjustment calculation below.|alert-warning}} | ||

| − | The canopy projection area (CP) is the perceived tree canopy | + | The canopy projection area (CP) is the perceived tree canopy area at maturity and is given by |

<math>CP = Π (d/2)^2</math> | <math>CP = Π (d/2)^2</math> | ||

| Line 115: | Line 127: | ||

where d is the diameter of the canopy as measured at the dripline (feet). | where d is the diameter of the canopy as measured at the dripline (feet). | ||

| − | CP varies by tree species. | + | CP varies by tree species. Refer to the [[Tree species list - morphology|Tree Species List]] for these values. Default values can be used in place of calculating CP. Defaults for CP are based on tree size and are |

*315 for a small tree; | *315 for a small tree; | ||

*490 for a medium sized tree; and | *490 for a medium sized tree; and | ||

*707 for a large tree. | *707 for a large tree. | ||

| − | The leaf area index (LAI) should be stratified by type into either | + | The leaf area index (LAI) is a dimensionless measure that quantifies the amount of leaf material in a canopy. LAI should be stratified by type into either |

*deciduous tree species (LAI = 3.5 for small trees, 4.1 for medium-sized trees, and 4.7 for large trees), or | *deciduous tree species (LAI = 3.5 for small trees, 4.1 for medium-sized trees, and 4.7 for large trees), or | ||

*coniferous tree species (LAI = 5.47). | *coniferous tree species (LAI = 5.47). | ||

| − | These values are based on collected research for global leaf area from 1932-2000 ( | + | These values are based on collected research for global leaf area from 1932-2000 (Scurlock, Asner and Gower, 2002). |

| − | The evaporation rate (E<sub>rate</sub>) per unit time can be calculated using a pan evaporation rate for the given area, as available at [http://www.noaa.gov/ NOAA]. | + | The evaporation rate (E<sub>rate</sub>) per unit time can be calculated using a pan evaporation rate for the given area, as available at [http://www.noaa.gov/ NOAA]. This should be estimated as a per day value. |

| − | The evaporation ratio (E<sub>ratio</sub>) is the equivalent that accounts for the efficiency of the leaves to transpire the available soil water or, alternately, the stomatal resistance of the canopy to transpiration and water movement. This is set at 0.20, or 20 percent based on research by | + | The evaporation ratio (E<sub>ratio</sub>) is the equivalent that accounts for the efficiency of the leaves to transpire the available soil water or, alternately, the stomatal resistance of the canopy to <span title="The loss of water as vapor from plants at their surfaces, primarily through stomata."> '''transpiration'''</span> and water movement. This is set at 0.20, or 20 percent based on research by Lindsey and Bassuk (1991). This means that a 1 square centimeter leaf transpires only about 1/5 as much as 1 square centimeter of pan surface. |

If the soil volume is less than the [[Design guidelines for soil characteristics - tree trenches and tree boxes#Recommended minimum soil volume requirements for urban trees|recommended volume]], the theoretical ET must be adjusted. Since the recommended soil volume equals 2 times the canopy project area (CP), the adjustment term is given by | If the soil volume is less than the [[Design guidelines for soil characteristics - tree trenches and tree boxes#Recommended minimum soil volume requirements for urban trees|recommended volume]], the theoretical ET must be adjusted. Since the recommended soil volume equals 2 times the canopy project area (CP), the adjustment term is given by | ||

| Line 144: | Line 156: | ||

===Volume credit calculations - underdrain=== | ===Volume credit calculations - underdrain=== | ||

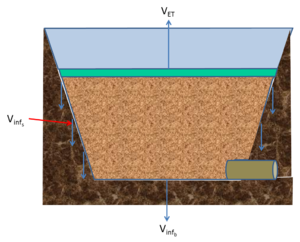

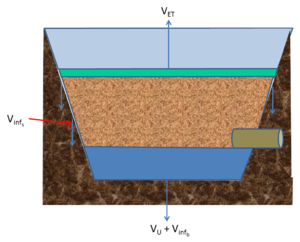

| − | Volume credits for a tree system with an underdrain include the ET and interception credits discussed above and an infiltration credit. The main design variables impacting the infiltration volume credit include whether the underdrain is elevated above the native soils and if an impermeable liner on the sides or bottom of the basin is used. Other design variables include media top surface area, underdrain location, basin bottom area, total depth of media, soil water holding capacity and media porosity, and infiltration rate of underlying soils. The total volume credit (V<sub>inf</sub>), in cubic feet, is given by | + | [[file:Bioretention water loss bottom underdrain.png|300px|thumb|alt=water loss mechanisms bioretention with underdrain at bottom|<font size=3>Schematic illustrating the different water loss terms for a biofiltration or tree trench BMP with an underdrain at the bottom.</font size>]] |

| + | |||

| + | [[file:Bioretention water loss raised underdrain.png|300px|thumb|alt=water loss mechanisms bioretention with raised underdrain|<font size=3>Schematic illustrating the different water loss terms for a biofiltration or tree trench BMP with a raised underdrain.</font size>]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Volume credits for a tree system with an underdrain include the ET and interception credits discussed above and an infiltration credit. The main design variables impacting the infiltration volume credit include whether the underdrain is elevated above the native soils and if an <span title="Impermeable means not allowing something, such as water, to pass through. Some materials considered impermeable may actually allow water to pass through at very slow rates, such as 10(-8) cm/sec."> '''impermeable'''</span> liner on the sides or bottom of the basin is used. Other design variables include media top surface area, underdrain location, basin bottom area, total depth of media, soil <span title="The ability of a certain soil texture to physically hold water against the force of gravity"> '''water holding capacity'''</span> and media porosity, and infiltration rate of underlying soils. The total volume credit (V<sub>inf</sub>), in cubic feet, is given by | ||

<math> V_{inf} = V_{inf_b}\ + V_{inf_s}\ + V_U + V_{ET}\ + V_I </math> | <math> V_{inf} = V_{inf_b}\ + V_{inf_s}\ + V_U + V_{ET}\ + V_I </math> | ||

| Line 162: | Line 178: | ||

where | where | ||

| − | :I<sub>R</sub> = [ | + | :I<sub>R</sub> = <span title="The assumed infiltration rate into soil or engineered media when determining the dimensions (depth, surface area) of a stormwater practice."> '''[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Design_infiltration_rate_as_a_function_of_soil_texture_for_bioretention_in_Minnesota design infiltration rate]''' </span> of underlying soil (inches per hour); |

:A<sub>B</sub> = surface area at the bottom of the basin (square feet); and | :A<sub>B</sub> = surface area at the bottom of the basin (square feet); and | ||

:DDT = drawdown time for ponded water (hours). | :DDT = drawdown time for ponded water (hours). | ||

| − | The [ | + | {{alert|The MIDS calculator assigns a default value of 0.06 inches per hour, equivalent to a D soil, to I<sub>R</sub>. This is based on the assumption that most water will drain to the underdrain, but that some loss to underlying soil will occur. A conservative approach assuming a D soil was thus chosen.|alert-info}} |

| + | |||

| + | The [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Construction_stormwater_program Construction Stormwater permit] requires drawdown within 48 hours and recommends 24 hours when discharges are to a trout stream. With a properly functioning underdrain, the drawdown time is likely to be considerably less than 48 hours. | ||

Volume credit for infiltration through the sides of the basin is accounted for only if the sides of the basin are not lined with an impermeable liner. Volume credit for infiltration through the sides of the basin is given by | Volume credit for infiltration through the sides of the basin is accounted for only if the sides of the basin are not lined with an impermeable liner. Volume credit for infiltration through the sides of the basin is given by | ||

| Line 175: | Line 193: | ||

:A<sub>M</sub> = the area at the media surface (square feet); and | :A<sub>M</sub> = the area at the media surface (square feet); and | ||

:A<sub>U</sub> = the surface area at the underdrain (square feet). | :A<sub>U</sub> = the surface area at the underdrain (square feet). | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{alert|The MIDS calculator assigns a default value of 0.06 inches per hour, equivalent to a D soil, to I<sub>R</sub>. This is based on the assumption that most water will drain to the underdrain, but that some loss to underlying soil will occur. A conservative approach assuming a D soil was thus chosen.|alert-info}} | ||

This equation assumes water will infiltrate through the entire sideslope area during the period when water is being drawn down. This is not the case, however, since the water level will decline in the BMP. The MIDS calculator assumes a linear drop in water level and thus divides the right hand term in the above equation by 2. | This equation assumes water will infiltrate through the entire sideslope area during the period when water is being drawn down. This is not the case, however, since the water level will decline in the BMP. The MIDS calculator assumes a linear drop in water level and thus divides the right hand term in the above equation by 2. | ||

| Line 190: | Line 210: | ||

This equation assumes water between the [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Soil_water_storage_properties soil porosity and field capacity] will infiltrate into the underlying soil. Water stored below the underdrain should infiltrate within a specified drawdown time. The construction stormwater permit has a 48 hour requirement for drawdown (24 hours is recommended when discharges are to trout streams). | This equation assumes water between the [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Soil_water_storage_properties soil porosity and field capacity] will infiltrate into the underlying soil. Water stored below the underdrain should infiltrate within a specified drawdown time. The construction stormwater permit has a 48 hour requirement for drawdown (24 hours is recommended when discharges are to trout streams). | ||

| − | The ET and infiltration credits are assumed to be instantaneous values based on the design capacity of the BMP for a specific storm event. Instantaneous volume reduction, also termed event based volume reduction, can be converted to annual volume reduction percentages using the [ | + | The ET and infiltration credits are assumed to be instantaneous values based on the design capacity of the BMP for a specific storm event. Instantaneous volume reduction, also termed event based volume reduction, can be converted to annual volume reduction percentages using the [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=MIDS_calculator MIDS calculator] or other appropriate modeling tools. Assuming an instantaneous volume will somewhat overestimate actual storage when the majority of water is being captured by the underdrains. |

The volume of water passing through underdrains can be determined by subtracting the volume loss (V) from the volume of water instantaneously captured by the BMP. No volume reduction credit is given for filtered stormwater that exits through the underdrain, but the volume of filtered water can be used in the calculation of pollutant removal credits through filtration. | The volume of water passing through underdrains can be determined by subtracting the volume loss (V) from the volume of water instantaneously captured by the BMP. No volume reduction credit is given for filtered stormwater that exits through the underdrain, but the volume of filtered water can be used in the calculation of pollutant removal credits through filtration. | ||

| Line 196: | Line 216: | ||

===Example calculation=== | ===Example calculation=== | ||

| − | A parking lot is developed and will contain tree trenches containing red maple (Acer rubrum). The tree trench has 1000 cubic feet of sandy loam per tree. Note that the following calculations are on a per tree basis. Total volume credit for the BMP will equal the per tree value times the number of trees, assuming all trees are of the same relative size (large in this case). | + | A parking lot is developed and will contain tree trenches containing red maple (Acer rubrum). The tree trench has 1000 cubic feet of sandy loam per tree. Note that the following calculations are on a per tree basis. Total volume credit for the BMP will equal the per tree value times the number of trees, assuming all trees are of the same relative size (large in this case). Soil information is from the [[Soil water storage properties]] table. |

====Infiltration credit==== | ====Infiltration credit==== | ||

| Line 220: | Line 240: | ||

The interception credit is given by | The interception credit is given by | ||

| − | <math>707 (0. | + | <math>707 (0.14/12) = 8.14 cubic feet</math> |

The division by 12 converts the calculation to feet. | The division by 12 converts the calculation to feet. | ||

====Total credit==== | ====Total credit==== | ||

| − | The total credit is the sum of the infiltration, ET and interception credits and equals (310 + 28.2 + | + | The total credit is the sum of the infiltration, ET and interception credits and equals (310 + 28.2 + 8.1) or 346.3 cubic feet. |

===Total suspended solids credit calculations=== | ===Total suspended solids credit calculations=== | ||

| Line 247: | Line 267: | ||

:EMC<sub>TSS</sub> is the event mean TSS concentration in runoff water entering the BMP (milligrams per liter). | :EMC<sub>TSS</sub> is the event mean TSS concentration in runoff water entering the BMP (milligrams per liter). | ||

| − | The EMC<sub>TSS</sub> entering the BMP is a function of the contributing land use and treatment by upstream tributary BMPs. For more information on EMC values for TSS, [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Total_Suspended_Solids_%28TSS%29_in_stormwater link here]. If there is no underdrain, | + | The EMC<sub>TSS</sub> entering the BMP is a function of the contributing land use and treatment by upstream tributary BMPs. For more information on EMC values for TSS, [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Total_Suspended_Solids_%28TSS%29_in_stormwater link here]. If there is no underdrain, the water quality volume (V<sub>WQ)</sub>) is used in this calculation. |

Removal for the filtered portion is less than 100 percent. The event-based mass of pollutant removed through filtration, in pounds, is given by | Removal for the filtered portion is less than 100 percent. The event-based mass of pollutant removed through filtration, in pounds, is given by | ||

| Line 257: | Line 277: | ||

:R<sub>TSS</sub> is the TSS pollutant removal percentage for filtered runoff. | :R<sub>TSS</sub> is the TSS pollutant removal percentage for filtered runoff. | ||

| − | The [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Pollutant_removal_percentages_for_bioretention_BMPs Stormwater Manual] provides a recommended value for R<sub>TSS</sub> of 0. | + | The [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Pollutant_removal_percentages_for_bioretention_BMPs Stormwater Manual] provides a recommended value for R<sub>TSS</sub> of 0.80 (80 percent removal) for filtered water. Alternate justified percentages for TSS removal can be used if proven to be applicable to the BMP design. |

The above calculations may be applied on an event or annual basis and are given by | The above calculations may be applied on an event or annual basis and are given by | ||

| Line 301: | Line 321: | ||

:the second term on the right side of the equation represents the removal of dissolved phosphorus; and | :the second term on the right side of the equation represents the removal of dissolved phosphorus; and | ||

:D<sub>MU<sub>max=2</sub></sub> = the media depth above the underdrain, up to a maximum of 2 feet. | :D<sub>MU<sub>max=2</sub></sub> = the media depth above the underdrain, up to a maximum of 2 feet. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The assumption of 55 percent particulate phosphorus and 45 percent dissolved phosphorus is likely inaccurate for certain land uses, such as industrial, transportation, and some commercial areas. Studies indicate particulate phosphorus comprises a greater percent of total phosphorus in these land uses. It may therefore be appropriate to modify the above equation with locally derived ratios for particulate and dissolved phosphorus. For more information on fractionation of phosphorus in stormwater runoff, [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Event_mean_concentrations_of_total_and_dissolved_phosphorus_in_stormwater_runoff#Ratios_of_particulate_to_dissolved_phosphorus link here]. | ||

The following table can be used to calculate phosphorus credits. | The following table can be used to calculate phosphorus credits. | ||

| Line 349: | Line 371: | ||

===Credits based on models=== | ===Credits based on models=== | ||

| − | Users may opt to use a water quality model or calculator to compute volume, TSS and/or TP pollutant removal for the purpose of determining credits. The available models described below are commonly used by water resource professionals, but are not explicitly endorsed or required by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. Furthermore, many of the models listed below cannot be used to determine compliance with the Construction Stormwater General permit since the permit requires the water quality volume to be calculated as an | + | {{alert|The model selected depends on your objectives. For compliance with the Construction Stormwater permit, the model must be based on the assumption that an instantaneous volume is captured by the BMP.|alert-danger}} |

| + | |||

| + | Users may opt to use a water quality model or calculator to compute volume, TSS and/or TP pollutant removal for the purpose of determining credits. The available models described below are commonly used by water resource professionals, but are not explicitly endorsed or required by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. Furthermore, many of the models listed below cannot be used to determine compliance with the Construction Stormwater General permit since the permit requires the water quality volume to be calculated as an <span title="The maximum volume of water that can be retained by a stormwater practice (bmp) if the water was instantaneously added to the practice. It equals the depth of the practice times the average area of the practice. For some bmps (e.g. bioretention, infiltration trenches and basins, swales with check dams), the volume is the water stored or retained above the media, while for other practices (e.g. permeable pavement, tree trenches) the volume is the water stored or retained within the media."> '''instantaneous volume'''</span>. | ||

Use of models or calculators for the purpose of computing pollutant removal credits should be supported by detailed documentation, including: | Use of models or calculators for the purpose of computing pollutant removal credits should be supported by detailed documentation, including: | ||

| Line 364: | Line 388: | ||

===The Simple Method and MPCA Estimator=== | ===The Simple Method and MPCA Estimator=== | ||

| − | The Simple Method is a technique used for estimating storm pollutant export delivered from urban development sites. Pollutant loads are estimated as the product of mean | + | The Simple Method is a technique used for estimating storm pollutant export delivered from urban development sites. Pollutant loads are estimated as the product of <span title="The average pollutant concentration for a given stormwater event, expressed in units of mass per volume (e.g., mg/L)"> '''event mean concentration'''</span> and runoff depths over specified periods of time (usually annual or seasonal). The method was developed to provide an easy yet reasonably accurate means of predicting the change in pollutant loadings in response to development. [http://www.stormwatercenter.net/Library/Practice/13.pdf Ohrel] (2000) states: "In general, the Simple Method is most appropriate for small watersheds (<640 acres) and when quick and reasonable stormwater pollutant load estimates are required". Rainfall data, land use (runoff coefficients), land area, and pollutant concentration are needed to use the Simple Method. For more information on the Simple Method, see [http://www.stormwatercenter.net/monitoring%20and%20assessment/simple%20meth/simple.htm The Simple method to Calculate Urban Stormwater Loads] or [[The Simple Method for estimating phosphorus export]]. |

| − | Some simple stormwater calculators utilize the Simple Method ([ | + | Some simple stormwater calculators utilize the Simple Method ([https://www.epa.gov/nps/spreadsheet-tool-estimating-pollutant-loads-stepl EPA STEPL], [https://www.stormwatercenter.net/monitoring%20and%20assessment/watershed_treatment_model.htm Watershed Treatment Model]). The MPCA developed a simple calculator for estimating load reductions for TSS, total phosphorus, and bacteria. Called the [http://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Guidance_and_examples_for_using_the_MPCA_Estimator '''MPCA Estimator'''], this tool was developed specifically for complying with the [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Forms,_guidance,_and_resources_for_completing_the_TMDL_annual_report_form MS4 General Permit TMDL annual reporting requirement]. The MPCA Estimator provides default values for pollutant concentration, <span title="The runoff coefficient (C) is a dimensionless coefficient relating the amount of runoff to the amount of precipitation received. It is a larger value for areas with low infiltration and high runoff (pavement, steep gradient), and lower for permeable, well vegetated areas (forest, flat land)."> [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Runoff_coefficients_for_5_to_10_year_storms '''runoff coefficients''']</span> for different land uses, and precipitation, although the user can modify these and is encouraged to do so when local data exist. The user is required to enter area for different land uses and area treated by BMPs within each of the land uses. BMPs include infiltrators (e.g. bioinfiltration, infiltration basin, tree trench, permeable pavement, etc.), filters (biofiltration, sand filter, green roof), constructed ponds and wetlands, and swales/filters. The MPCA Estimator includes standard removal efficiencies for these BMPs, but the user can modify those values if better data are available. Output from the calculator is given as a load reduction (percent, mass, or number of bacteria) from the original estimated load. |

| − | {{alert|The MPCA Estimator should not be used for modeling a stormwater system or selecting BMPs.|alert- | + | {{alert|The MPCA Estimator should not be used for modeling a stormwater system or selecting BMPs.|alert-warning}} |

Because the MPCA Estimator does not consider BMPs in series, makes simplifying assumptions about runoff and pollutant removal processes, and uses generalized default information, it should only be used for estimating pollutant reductions from an estimated load. It is not intended as a decision-making tool. | Because the MPCA Estimator does not consider BMPs in series, makes simplifying assumptions about runoff and pollutant removal processes, and uses generalized default information, it should only be used for estimating pollutant reductions from an estimated load. It is not intended as a decision-making tool. | ||

| − | '''Download MPCA Estimator here | + | '''[https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=File:MPCA_simple_estimator_version_3.0_March_5_2021.xlsx Download MPCA Estimator here]''' |

| − | |||

| − | |||

===MIDS Calculator=== | ===MIDS Calculator=== | ||

| Line 391: | Line 413: | ||

*select the median value from pollutant reduction databases that report a range of reductions, such as from the International BMP Database; | *select the median value from pollutant reduction databases that report a range of reductions, such as from the International BMP Database; | ||

*select a pollutant removal reduction from literature that studied a BMP with site characteristics and climate similar to the device being considered for credits; | *select a pollutant removal reduction from literature that studied a BMP with site characteristics and climate similar to the device being considered for credits; | ||

| − | *review the article to determine that the design principles of the studied BMP are close to the design recommendations for Minnesota, as described in [ | + | *review the article to determine that the design principles of the studied BMP are close to the design recommendations for Minnesota, as described in [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Trees this manual] and/or by a local permitting agency; and |

*give preference to literature that has been published in a peer-reviewed publication. | *give preference to literature that has been published in a peer-reviewed publication. | ||

| Line 397: | Line 419: | ||

The following references summarize pollutant reduction values from multiple studies or sources that could be used to determine credits for bioretention systems. Users should note that there is a wide range of monitored pollutant removal effectiveness in the literature. Before selecting a literature value, users should compare the characteristics of the monitored site in the literature against the characteristics of the proposed bioretention device, considering such conditions as watershed characteristics, bioretention sizing, soil infiltration rates, and climate factors. | The following references summarize pollutant reduction values from multiple studies or sources that could be used to determine credits for bioretention systems. Users should note that there is a wide range of monitored pollutant removal effectiveness in the literature. Before selecting a literature value, users should compare the characteristics of the monitored site in the literature against the characteristics of the proposed bioretention device, considering such conditions as watershed characteristics, bioretention sizing, soil infiltration rates, and climate factors. | ||

| − | *[ | + | *[https://bmpdatabase.org/ International Stormwater Best Management Practices (BMP) Database] Pollutant Category Summary Statistical Addendum: TSS, Bacteria, Nutrients, and Metals |

**Compilation of BMP performance studies published through 2011 | **Compilation of BMP performance studies published through 2011 | ||

**Provides values for TSS, Bacteria, Nutrients, and Metals | **Provides values for TSS, Bacteria, Nutrients, and Metals | ||

**Applicable to grass strips, bioretention, bioswales, detention basins, green roofs, manufactured devices, media filters, porous pavements, wetland basins, and wetland channels | **Applicable to grass strips, bioretention, bioswales, detention basins, green roofs, manufactured devices, media filters, porous pavements, wetland basins, and wetland channels | ||

| − | *[ | + | *[http://lshs.tamu.edu/docs/lshs/end-notes/updated%20bmp%20removal%20efficiencies%20from%20the%20national%20pollutant%20re-2854375963/updated%20bmp%20removal%20efficiencies%20from%20the%20national%20pollutant%20removal%20database.pdf Updated BMP Removal Efficiencies from the National Pollutant Removal Database (2007) & Acceptable BMP Table for Virginia] |

| − | ** | + | **Provides data for several structural and non-structural BMP performance evaluations |

| − | |||

| − | |||

*[http://www.epa.state.il.us/green-infrastructure/docs/draft-final-report.pdf The Illinois Green Infrastructure Study] | *[http://www.epa.state.il.us/green-infrastructure/docs/draft-final-report.pdf The Illinois Green Infrastructure Study] | ||

**Figure ES-1 summarizes BMP effectiveness | **Figure ES-1 summarizes BMP effectiveness | ||

**Provides values for TN, TSS, peak flows / runoff volumes | **Provides values for TN, TSS, peak flows / runoff volumes | ||

**Applicable to permeable pavements, constructed wetlands, infiltration, detention, filtration, and green roofs | **Applicable to permeable pavements, constructed wetlands, infiltration, detention, filtration, and green roofs | ||

| − | *[ | + | *[https://www.des.nh.gov/sites/g/files/ehbemt341/files/documents/2020-01/wd-08-20b.pdf New Hampshire Stormwater Manual] |

**Volume 2, Appendix B summarizes BMP effectiveness | **Volume 2, Appendix B summarizes BMP effectiveness | ||

**Provides values for TSS, TN, and TP removal | **Provides values for TSS, TN, and TP removal | ||

**Applicable to basins and wetlands, stormwater wetlands, infiltration practices, filtering practices, treatment swales, vegetated buffers, and pre-treatment practices | **Applicable to basins and wetlands, stormwater wetlands, infiltration practices, filtering practices, treatment swales, vegetated buffers, and pre-treatment practices | ||

| − | *[ | + | *[https://www.wri.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/FinalWR03R001.pdf Design Guidelines for Stormwater Bioretention Facilities]. University of Wisconsin, Madison |

**Table 2-1 summarizes typical removal rates | **Table 2-1 summarizes typical removal rates | ||

**Provides values for TSS, metals, TP, TKN, ammonium, organics, and bacteria | **Provides values for TSS, metals, TP, TKN, ammonium, organics, and bacteria | ||

**Applicable for bioretention | **Applicable for bioretention | ||

| − | *[ | + | *[https://www3.epa.gov/region1/npdes/stormwater/tools/BMP-Performance-Analysis-Report.pdf BMP Performance Analysis]. Prepared for US EPA Region 1, Boston MA. |

**Appendix B provides pollutant removal performance curves | **Appendix B provides pollutant removal performance curves | ||

**Provides values for TP, TSS, and zinc | **Provides values for TP, TSS, and zinc | ||

| Line 427: | Line 447: | ||

===Credits based on field monitoring=== | ===Credits based on field monitoring=== | ||

| − | Field monitoring may be | + | Field monitoring may be made in lieu of desktop calculations or models/calculators as described. Careful planning is HIGHLY RECOMMENDED before commencing a program to monitor the performance of a BMP. The general steps involved in planning and implementing BMP monitoring include the following. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | #Establish the objectives and goals of the monitoring. When monitoring BMP performance, typical objectives may include the following. | |

| − | + | ##Which pollutants will be measured? | |

| − | + | ##Will the monitoring study the performance of a single BMP or multiple BMPs? | |

| − | + | ##Are there any variables that will affect the BMP performance? Variables could include design approaches, maintenance activities, rainfall events, rainfall intensity, etc. | |

| − | + | ##Will the results be compared to other BMP performance studies? | |

| − | + | ##What should be the duration of the monitoring period? Is there a need to look at the annual performance vs the performance during a single rain event? Is there a need to assess the seasonal variation of BMP performance? | |

| − | + | #Plan the field activities. Field considerations include | |

| − | + | ##equipment selection and placement; | |

| − | + | ##sampling protocols including selection, storage, and delivery to the laboratory; | |

| − | + | ##laboratory services; | |

| − | + | ##health and Safety plans for field personnel; | |

| − | + | ##record keeping protocols and forms; and | |

| − | + | ##quality control and quality assurance protocols | |

| − | + | #Execute the field monitoring | |

| + | #Analyze the results | ||

| + | |||

| + | This manual contains the following guidance for monitoring. | ||

| + | *[[Recommendations and guidance for utilizing monitoring to meet TMDL permit requirements]] | ||

| + | *[[Recommendations and guidance for utilizing lake monitoring to meet TMDL permit requirements]] | ||

| + | *[[Recommendations and guidance for utilizing stream monitoring to meet TMDL permit requirements]] | ||

| + | *[[Recommendations and guidance for utilizing major stormwater outfall monitoring to meet TMDL permit requirements]] | ||

| + | *[[Recommendations and guidance for utilizing stormwater best management practice monitoring to meet TMDL permit requirements]] | ||

The following guidance manuals have been developed to assist BMP owners and operators on how to plan and implement BMP performance monitoring. | The following guidance manuals have been developed to assist BMP owners and operators on how to plan and implement BMP performance monitoring. | ||

| − | :[ | + | |

| − | Geosyntec Consultants and Wright Water Engineers prepared this guide in 2009 with support from the USEPA, Water Environment Research Foundation, Federal Highway Administration, and the Environment and Water Resource Institute of the American Society of Civil Engineers. This guide was developed to improve and standardize the protocols for all BMP monitoring and to provide additional guidance for Low Impact Development (LID) BMP monitoring. | + | :[https://www3.epa.gov/npdes/pubs/montcomplete.pdf '''Urban Stormwater BMP Performance Monitoring'''] |

| − | Highlighted chapters in this manual include: | + | Geosyntec Consultants and Wright Water Engineers prepared this guide in 2009 with support from the USEPA, Water Environment Research Foundation, Federal Highway Administration, and the Environment and Water Resource Institute of the American Society of Civil Engineers. This guide was developed to improve and standardize the protocols for all BMP monitoring and to provide additional guidance for Low Impact Development (LID) BMP monitoring. Highlighted chapters in this manual include: |

| − | *Chapter 2: | + | *Chapter 2: Developing a monitoring plan. Describes a seven-step approach for developing a monitoring plan for collection of data to evaluate BMP effectiveness. |

| − | * | + | *Chapter 3: Methods and Equipment for hydrologic and hydraulic monitoring |

| − | *Chapters 5 | + | *Chapter 4: Methods and equipment for water quality monitoring |

| + | *Chapters 5 (Implementation) and 6 (Data Management, Evaluation and Reporting) | ||

*Chapter 7: BMP Performance Analysis | *Chapter 7: BMP Performance Analysis | ||

| − | *Chapters 8, 9, | + | *Chapters 8 (LID Monitoring), 9 (LID data interpretation]), and 10 (Case studies). |

:[http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/nchrp_rpt_565.pdf '''Evaluation of Best Management Practices for Highway Runoff Control (NCHRP Report 565)'''] | :[http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/nchrp_rpt_565.pdf '''Evaluation of Best Management Practices for Highway Runoff Control (NCHRP Report 565)'''] | ||

| − | AASHTO (American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials) and the FHWA (Federal Highway Administration) sponsored this 2006 research report, which was authored by Oregon State University, Geosyntec Consultants, the University of Florida, and the Low Impact Development Center. The primary purpose of this report is to advise on the selection and design of BMPs that are best suited for highway runoff. The document includes | + | AASHTO (American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials) and the FHWA (Federal Highway Administration) sponsored this 2006 research report, which was authored by Oregon State University, Geosyntec Consultants, the University of Florida, and the Low Impact Development Center. The primary purpose of this report is to advise on the selection and design of BMPs that are best suited for highway runoff. The document includes chapters on performance monitoring that may be a useful reference for BMP performance monitoring, especially for the performance assessment of a highway BMP. |

*Chapter 4: Stormwater Characterization | *Chapter 4: Stormwater Characterization | ||

**4.2: General Characteristics and Pollutant Sources | **4.2: General Characteristics and Pollutant Sources | ||

| Line 464: | Line 493: | ||

**8.6: Overall Hydrologic and Water Quality Performance Evaluation | **8.6: Overall Hydrologic and Water Quality Performance Evaluation | ||

*Chapter 10: Hydrologic Evaluation | *Chapter 10: Hydrologic Evaluation | ||

| − | **10.5: Performance Verification and Design Optimization | + | **10.5: Performance Verification and Design Optimization |

| − | :[ | + | :[https://www.wef.org/globalassets/assets-wef/3---resources/topics/o-z/stormwater/stormwater-institute/wef-stepp-white-paper_final_02-06-14.pdf '''Investigation into the Feasibility of a National Testing and Evaluation Program for Stormwater Products and Practices'''] |

| − | In 2014 the Water Environment Federation released this White Paper that investigates the feasibility of a national program for the testing of stormwater products and practices. | + | *In 2014 the Water Environment Federation released this White Paper that investigates the feasibility of a national program for the testing of stormwater products and practices. The report does not include any specific guidance on the monitoring of a BMP, but it does include a summary of the existing technical evaluation programs that could be consulted for testing results for specific products (see Table 1 on page 8). |

| − | : | + | :'''Caltrans Stormwater Monitoring Guidance Manual (Document No. CTSW-OT-13-999.43.01)'''] |

| − | The most current version of this manual was released by the State of California, Department of Transportation in November 2013. As with the other monitoring manuals described, this manual does include guidance on planning a stormwater monitoring program. However, this manual is among the most thorough for field activities. Relevant chapters include | + | |

| + | The most current version of this manual was released by the State of California, Department of Transportation in November 2013. As with the other monitoring manuals described, this manual does include guidance on planning a stormwater monitoring program. However, this manual is among the most thorough for field activities. Relevant chapters include. | ||

*Chapter 4: Monitoring Methods and Equipment | *Chapter 4: Monitoring Methods and Equipment | ||

*Chapter 5: Analytical Methods and Laboratory Selection | *Chapter 5: Analytical Methods and Laboratory Selection | ||

| Line 481: | Line 511: | ||

*Chapter 15: Gross Solids Monitoring | *Chapter 15: Gross Solids Monitoring | ||

| − | :[http://stormwaterbook.safl.umn.edu/ | + | :[http://stormwaterbook.safl.umn.edu/ '''Optimizing Stormwater Treatment Practices: A Handbook of Assessment and Maintenance'''] |

| − | This online manual was developed in 2010 by Andrew Erickson, Peter Weiss, and John Gulliver from the University of Minnesota and St. Anthony Falls Hydraulic Laboratory with funding provided by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. The manual advises on a four-level process to assess the performance of a Best Management Practice | + | |

| − | *Level 1: Visual Inspection | + | This online manual was developed in 2010 by Andrew Erickson, Peter Weiss, and John Gulliver from the University of Minnesota and St. Anthony Falls Hydraulic Laboratory with funding provided by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. The manual advises on a four-level process to assess the performance of a Best Management Practice. |

| − | *Level 2: Capacity Testing | + | *Level 1: [https://stormwaterbook.safl.umn.edu/assessment-programs/visual-inspection Visual Inspection] |

| − | *Level 3: Synthetic Runoff Testing | + | *Level 2: [https://stormwaterbook.safl.umn.edu/assessment-programs/capacity-testing Capacity Testing] |

| − | *Level 4: Monitoring | + | *Level 3: [http://stormwaterbook.safl.umn.edu/assessment-programs/synthetic-runoff-testing Synthetic Runoff Testing] |

| − | + | *Level 4: [https://stormwaterbook.safl.umn.edu/assessment-programs/monitoring Monitoring] | |

| + | |||

| + | Level 1 activities do not produce numerical performance data that could be used to obtain a stormwater management credit. BMP owners and operators who are interested in using data obtained from Levels 2 and 3 should consult with the MPCA or other regulatory agency to determine if the results are appropriate for credit calculations. Level 4, Monitoring, is the method most frequently used for assessment of the performance of a BMP. | ||

Use these links to obtain detailed information on the following topics related to BMP performance monitoring: | Use these links to obtain detailed information on the following topics related to BMP performance monitoring: | ||

| − | *[ | + | *[https://stormwaterbook.safl.umn.edu/water-budget-measurement Water Budget Measurement] |

| − | *[ | + | *[https://stormwaterbook.safl.umn.edu/sampling-methods Sampling Methods] |

| − | *[ | + | *[https://stormwaterbook.safl.umn.edu/analysis-water-and-soils Analysis of Water and Soils] |

| − | *[ | + | *[https://stormwaterbook.safl.umn.edu/data-analysis Data Analysis for Monitoring] |

==Other pollutants== | ==Other pollutants== | ||

| − | In addition to TSS and phosphorus, bioretention BMPs can reduce loading of other pollutants. According to the [ | + | In addition to TSS and phosphorus, bioretention BMPs can reduce loading of other pollutants. According to the [https://bmpdatabase.org/ International Stormwater Database], studies have shown that bioretention BMPs are effective at reducing concentrations of pollutants, including metals, and bacteria. A compilation of the pollutant removal capabilities from a review of literature are summarized below. |

{{:Relative pollutant reduction for biofiltration}} | {{:Relative pollutant reduction for biofiltration}} | ||

==References and suggested reading== | ==References and suggested reading== | ||

| + | To see how some other cities are calculating tree credits, see [http://www.deeproot.com/blog/blog-entries/cities-that-are-pioneers-in-developing-storwmater-credit-systems-for-trees Cities That are Pioneers in Developing Stormwater Credit Systems for Trees] (Shanstrom, 2014) | ||

| + | |||

*Brown, Robert A., and William F. Hunt III. 2010. ''Impacts of media depth on effluent water quality and hydrologic performance of undersized bioretention cells.'' Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering 137, no. 3: 132-143. | *Brown, Robert A., and William F. Hunt III. 2010. ''Impacts of media depth on effluent water quality and hydrologic performance of undersized bioretention cells.'' Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering 137, no. 3: 132-143. | ||

*Brown, R. A., and W. F. Hunt. 2011. ''Underdrain configuration to enhance bioretention exfiltration to reduce pollutant loads''. Journal of Environmental Engineering 137, no. 11: 1082-1091. | *Brown, R. A., and W. F. Hunt. 2011. ''Underdrain configuration to enhance bioretention exfiltration to reduce pollutant loads''. Journal of Environmental Engineering 137, no. 11: 1082-1091. | ||

| Line 539: | Line 573: | ||

*Weiss, Peter T., John S. Gulliver, and Andrew J. Erickson. 2005. [http://www.lrrb.org/media/reports/200523.pdf The Cost and Effectiveness of Stormwater Management Practices Final Report.]. Published by: Minnesota Department of Transportation. | *Weiss, Peter T., John S. Gulliver, and Andrew J. Erickson. 2005. [http://www.lrrb.org/media/reports/200523.pdf The Cost and Effectiveness of Stormwater Management Practices Final Report.]. Published by: Minnesota Department of Transportation. | ||

*Wossink, G. A. A., and Bill Hunt. 2003. [http://www.bae.ncsu.edu/stormwater/PublicationFiles/EconStructuralBMPs2003.pdf The economics of structural stormwater BMPs in North Carolina]. Water Resources Research Institute of the University of North Carolina. | *Wossink, G. A. A., and Bill Hunt. 2003. [http://www.bae.ncsu.edu/stormwater/PublicationFiles/EconStructuralBMPs2003.pdf The economics of structural stormwater BMPs in North Carolina]. Water Resources Research Institute of the University of North Carolina. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <noinclude> | ||

==Related pages== | ==Related pages== | ||

| Line 561: | Line 597: | ||

**[[Calculating credits for swale]] | **[[Calculating credits for swale]] | ||

**[[Calculating credits for tree trenches and tree boxes]] | **[[Calculating credits for tree trenches and tree boxes]] | ||

| + | **[[Calculating credits for stormwater and rainwater harvest and use/reuse]] | ||

The following pages address incorporation of trees into stormwater management under paved surfaces | The following pages address incorporation of trees into stormwater management under paved surfaces | ||

| Line 576: | Line 613: | ||

*[[Requirements, recommendations and information for using trees with an underdrain as a BMP in the MIDS calculator]] | *[[Requirements, recommendations and information for using trees with an underdrain as a BMP in the MIDS calculator]] | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Level 3 - Best management practices/Structural practices/Tree trench and box]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Level 3 - Best management practices/Guidance and information/Pollutant removal and credits]] |

</noinclude> | </noinclude> | ||

Latest revision as of 18:43, 13 December 2022

| Recommended pollutant removal efficiencies, in percent, for tree trench/tree box BMPs. Sources. NOTE: removal efficiencies are 100 percent for water that is infiltrated. TSS=total suspended solids; TP=total phosphorus; PP=particulate phosphorus; DP=dissolved phosphorus; TN=total nitrogen | |||||||

| TSS | TP | PP | DP | TN | Metals | Bacteria | Hydrocarbons |

| 80 | link to table | link to table | link to table | 50 | 35 | 95 | 80 |

Credit refers to the quantity of stormwater or pollutant reduction achieved either by an individual best management practice (BMP) or cumulatively with multiple BMPs. Stormwater credits are a tool for local stormwater authorities who are interested in

- providing incentives to site developers to encourage the preservation of natural areas and the reduction of the volume of stormwater runoff being conveyed to a best management practice (BMP);

- complying with permit requirements, including antidegradation (see Construction permit; Municipal (MS4) permit);

- meeting the MIDS performance goal; or

- meeting or complying with water quality objectives, including total maximum daily load (TMDL) wasteload allocations (WLAs).

This page provides a discussion of how tree trench/tree box practices can achieve stormwater credits. Tree systems with and without underdrains are both discussed, with separate sections for each type of system as appropriate.

Contents

- 1 Overview

- 2 Methodology for calculating credits

- 3 Methods for calculating credits

- 4 Other pollutants

- 5 References and suggested reading

- 6 Related pages

Overview

Tree trenches and tree boxes are specialized bioretention practices practices. They are therefore terrestrial-based (up-land as opposed to wetland) water quality and water quantity control process. Tree systems consist of an engineered soil media designed to treat stormwater runoff via filtration through plant and soil media, evapotranspiration from trees, or through infiltration into underlying soil. * Pretreatment is REQUIRED for all bioretention facilities, including tree-based systems, to settle particulates before entering the BMP. Tree practices may be built with or without an underdrain. Other common components may include a stone aggregate layer to allow for increased retention storage and an impermeable liner on the bottom or sides of the facility if located near buildings, subgrade utilities, or in Karst formations.

Pollutant removal mechanisms

Like other bioretention practices, tree trenches and tree boxes have high nutrient and pollutant removal efficiencies (Mid-America Regional Council and American Public Works Association Manual of Best Management Practice BMPs for Stormwater Quality, 2012). Tree practices provide pollutant removal and volume reduction through filtration, evaporation, infiltration, transpiration, biological and microbiological uptake, and soil adsorption; the extent of these benefits is highly dependent on site specific conditions and design. In addition to phosphorus and total suspended solids (TSS), which are discussed in greater detail below, tree practices treat a wide variety of other pollutants.

Removal of phosphorus is dependent on the engineered media. Media mixes with high organic matter content typically leach phosphorus and can therefore contribute to water quality degradation. The Manual provides a detailed discussion of media mixes, including information on phosphorus retention.

Location in the treatment train

Stormwater treatment trains are multiple best management practices (BMPs) that work together to minimize the volume of stormwater runoff, remove pollutants, and reduce the rate of stormwater runoff being discharged to Minnesota wetlands, lakes and streams. Tree trenches and tree boxes can be incorporated anywhere in the stormwater treatment train but are most often located in upland areas of the treatment train. The strategic distribution of tree BMPs help control runoff close to the source where it is generated.

Methodology for calculating credits

This section describes the basic concepts and equations used to calculate credits for volume, Total Suspended Solids (TSS) and Total Phosphorus (TP). Specific methods for calculating credits are discussed later in this article.

Tree practices generate credits for volume, TSS, and TP. Practices with underdrains do not substantially reduce the volume of runoff but may qualify for a partial volume credit as a result of evapotranspiration, infiltration occurring through the sidewalls above the underdrain, and infiltration below the underdrain piping. Tree practices are effective at reducing concentrations of other pollutants including nitrogen, metals, bacteria, and hydrocarbons. This article does not provide information on calculating credits for pollutants other than TSS and TP, but references are provided that may be useful for calculating credits for other pollutants.

Assumptions and approach

In developing the credit calculations, it is assumed the tree practice is properly designed, constructed, and maintained in accordance with the Minnesota Stormwater Manual. If any of these assumptions is not valid, the BMP may not qualify for credits or credits should be reduced based on reduced ability of the BMP to achieve volume or pollutant reductions. For guidance on design, construction, and maintenance, see the appropriate article within the tree section of the Manual.

In the following discussion, the Water Quality Volume (VWQ) is delivered as an instantaneous volume to the BMP. The VWQ is stored within the filter media. The VWQ can vary depending on the stormwater management objective(s). For construction stormwater, VWQ is 1 inch times the new impervious surface area. For MIDS, VWQ is 1.1 inches times the impervious surface area.

Volume credit calculations - no underdrain

Volume credits are calculated based on the capacity of the BMP and its ability to permanently remove stormwater runoff via infiltration into the underlying soil, evapotranspiration (ET) from trees, and interception of rainfall by the tree canopy. The total volume credit, V in cubic feet, is given by

\( V = V_{inf_b}\ + V_{ET}\ + V_I \)

where

- Vinf is the volume of captured water that is infiltrated, in cubic feet;

- VET is the volume of captured water that is lost to evapotranspiration, in cubic feet; and

- VI is the volume of precipitation intercepted by the tree canopy, in cubic feet.

Interception credit

Water intercepted by a tree canopy may evaporate or be slowly released such that it does not contribute to stormwater runoff. An interception credit is given by a simplified value of the interception capacity (Ic) for deciduous and coniferous tree species [1].

- Ic coniferous = 0.40 inches (2.2 millimeters)

- Ic deciduous = 0.14 inches (1.1 millimeters)

These values intercept approximately 30% and 57% of annual rainfall over the canopy area.

This credit is per storm event.

Infiltration and ET credits