Difference between revisions of "Design, construction, operation and maintenance specifications for pretreatment vegetated filter strips"

m |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

The [http://tnpermanentstormwater.org/manual/13%20Chapter%205.4.5%20Filter%20Strips.pdf Tennessee Permanent Stormwater Management and Design Guidance Manual] states: "Filter strips are used to treat very small drainage areas of a few acres or less. The limiting design factor is the length of flow directed to the filter. As a rule, flow tends to concentrate after 100 feet of flow length for impervious surfaces, and 150 feet for pervious surfaces. When flow concentrates, it moves too rapidly to be effectively treated by a Filter Strip, unless an engineered level spreader is used. When the existing flow at a site is concentrated, a grass channel or a water quality swale should be used instead of a Filter Strip (Lantin and Barrett, 2005)." | The [http://tnpermanentstormwater.org/manual/13%20Chapter%205.4.5%20Filter%20Strips.pdf Tennessee Permanent Stormwater Management and Design Guidance Manual] states: "Filter strips are used to treat very small drainage areas of a few acres or less. The limiting design factor is the length of flow directed to the filter. As a rule, flow tends to concentrate after 100 feet of flow length for impervious surfaces, and 150 feet for pervious surfaces. When flow concentrates, it moves too rapidly to be effectively treated by a Filter Strip, unless an engineered level spreader is used. When the existing flow at a site is concentrated, a grass channel or a water quality swale should be used instead of a Filter Strip (Lantin and Barrett, 2005)." | ||

| − | The | + | The State of Washington DOT recommends a maximum flow path of 75 feet. |

===Flow velocity=== | ===Flow velocity=== | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

Soil conditions need to be assessed at the site before the pretreatment vegetated filter strip is installed. Most soils are suitable for a pretreatment vegetated filter strip, but some soils may require amendments to support healthy vegetation development. Establishing vegetation is key to the success of the pretreatment vegetated filter strip because the vegetation provides the mechanism for pretreatment. | Soil conditions need to be assessed at the site before the pretreatment vegetated filter strip is installed. Most soils are suitable for a pretreatment vegetated filter strip, but some soils may require amendments to support healthy vegetation development. Establishing vegetation is key to the success of the pretreatment vegetated filter strip because the vegetation provides the mechanism for pretreatment. | ||

| − | If the soil at a site is not deemed adequate to establish healthy vegetation, amending it with [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Turf#Compost compost] is an effective practice. Compost provides an effective organic amendment that will improve drainage, aeration, and nutrient balance. Soil amendments should be completed by adding 1 to 2 inches of well-decomposed compost to the top 6 to 8 inches of soil where the pretreatment vegetated filter strip will be installed. For more information on using compost as a soil amendment, see the [ | + | If the soil at a site is not deemed adequate to establish healthy vegetation, amending it with [https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php?title=Turf#Compost compost] is an effective practice. Compost provides an effective organic amendment that will improve drainage, aeration, and nutrient balance. Soil amendments should be completed by adding 1 to 2 inches of well-decomposed compost to the top 6 to 8 inches of soil where the pretreatment vegetated filter strip will be installed. For more information on using compost as a soil amendment, see the [https://extension.umn.edu/ University of Minnesota Extension webpage]. |

===Vegetation=== | ===Vegetation=== | ||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

*Abu-Zreig, M., R. P. Rudra, M. N. Lalonde, H. R. Whiteley, and N. K. Kaushik, 2004. ''Experimental Investigation of Runoff Reduction and Sediment Removal by Vegetated Filter Strips''. Hydrological Processes, Vol. 18, No. 11, pp. 2029–2037. | *Abu-Zreig, M., R. P. Rudra, M. N. Lalonde, H. R. Whiteley, and N. K. Kaushik, 2004. ''Experimental Investigation of Runoff Reduction and Sediment Removal by Vegetated Filter Strips''. Hydrological Processes, Vol. 18, No. 11, pp. 2029–2037. | ||

*Barrett, M. E.; P. M. Walsh; J. F. Malina, Jr.; R. J. Charbeneau, 1998. ''Performance of Vegetative Controls for Treating Highway Runoff''. Journal of Environmental Engineering, Vol. 124, No. 11, pp. 1121–1128. | *Barrett, M. E.; P. M. Walsh; J. F. Malina, Jr.; R. J. Charbeneau, 1998. ''Performance of Vegetative Controls for Treating Highway Runoff''. Journal of Environmental Engineering, Vol. 124, No. 11, pp. 1121–1128. | ||

| − | *Barret, M. E., A. Lantin, and S. Austrheim-Smith, 2004. | + | *Barret, M. E., A. Lantin, and S. Austrheim-Smith, 2004. ''Storm Water Pollutant Removal in Roadside Vegetated Buffer Strips''. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 1890, No. 1, pp. 129-140. |

*Blanco-Canqui, H., C. J. Gantzer, S. H. Anderson, and E. E. Alberts. 2004. ''Grass Barriers for Reduced Concentrated Flow Induced Soil and Nutrient Loss''. Soil Science Society of America Journal, Vol. 68, No. 6, pp. 1963-1972. | *Blanco-Canqui, H., C. J. Gantzer, S. H. Anderson, and E. E. Alberts. 2004. ''Grass Barriers for Reduced Concentrated Flow Induced Soil and Nutrient Loss''. Soil Science Society of America Journal, Vol. 68, No. 6, pp. 1963-1972. | ||

*California Environmental Protection Agency, 2014. [http://www.waterboards.ca.gov/water_issues/programs/trash_control/docs/trash_sr_061014.pdf Draft Amendments to Statewide Water Quality Control Plans to Control Trash]. Prepared by the California Environmental Protection Agency, Division of Water Quality, State Water Resources Control Board, Sacramento, CA. | *California Environmental Protection Agency, 2014. [http://www.waterboards.ca.gov/water_issues/programs/trash_control/docs/trash_sr_061014.pdf Draft Amendments to Statewide Water Quality Control Plans to Control Trash]. Prepared by the California Environmental Protection Agency, Division of Water Quality, State Water Resources Control Board, Sacramento, CA. | ||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

*Kayhanian, M., Suverkropp, C., Ruby, A., and Tsay, K. 2007. ''Characterization and Prediction of Highway Runoff Constituent Event Mean Concentration''. Journal of Environmental Management, Vol. 85, No. 2, pp. 279–295. | *Kayhanian, M., Suverkropp, C., Ruby, A., and Tsay, K. 2007. ''Characterization and Prediction of Highway Runoff Constituent Event Mean Concentration''. Journal of Environmental Management, Vol. 85, No. 2, pp. 279–295. | ||

*Lantin, A. and Barrett, M. 2005. ''Design and Pollutant Reduction of Vegetated Strips and Swales''. Impacts of Global Climate Change, pp. 1-11. | *Lantin, A. and Barrett, M. 2005. ''Design and Pollutant Reduction of Vegetated Strips and Swales''. Impacts of Global Climate Change, pp. 1-11. | ||

| − | *Maestre, A., and Pitt, R. 2005. [ | + | *Maestre, A., and Pitt, R. 2005. [https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/rwqcb9/water_issues/programs/stormwater/docs/wqip/2013-0001/J_References/J099.pdf The National Stormwater Quality Database, Version 1.1: A Compilation and Analysis of NPDES Stormwater Monitoring Information]. Prepared for the US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water, Washington, DC. |

*Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, 2008. [http://www.mass.gov/eea/agencies/massdep/water/regulations/massachusetts-stormwater-handbook.html Massachusetts Stormwater Handbook, Volume 2]. Prepared by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, Boston, MA. | *Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, 2008. [http://www.mass.gov/eea/agencies/massdep/water/regulations/massachusetts-stormwater-handbook.html Massachusetts Stormwater Handbook, Volume 2]. Prepared by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, Boston, MA. | ||

*Maniquiz-Redillas, M. C., F. K. Geronimo, and L. H. Kim, 2014. ''Investigation on the Effectiveness of Pretreatment in Stormwater Management Technologies''. Journal of Environmental Sciences, Vol. 26, No. 9, pp. 1824–1830. | *Maniquiz-Redillas, M. C., F. K. Geronimo, and L. H. Kim, 2014. ''Investigation on the Effectiveness of Pretreatment in Stormwater Management Technologies''. Journal of Environmental Sciences, Vol. 26, No. 9, pp. 1824–1830. | ||

| − | *North Carolina State Cooperative Extension Service, 2006. [https:// | + | *North Carolina State Cooperative Extension Service, 2006. [https://deq.nc.gov/media/17543/download Level Spreaders: Overview, Design, and Maintenance]. Prepared by Jon M. Hathaway and William F. Hunt, North Carolina State University. |

*New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, 2014. [http://www.njstormwater.org/bmp_manual2.htm NJ Stormwater Best Management Practices Manual]. Chapter 9.10 Standard for Vegetative Filters, prepared by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Watershed Management, Trenton, NJ. | *New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, 2014. [http://www.njstormwater.org/bmp_manual2.htm NJ Stormwater Best Management Practices Manual]. Chapter 9.10 Standard for Vegetative Filters, prepared by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Watershed Management, Trenton, NJ. | ||

*Battiata, J., S. Claggett, S. Crafton, D. Follansbee, D. Gasper, R. Greer, C. Hardman, T. Jordan, S. Stewart, A. Todd, R. Winston, and J. Zielinski, 2014. [http://www.chesapeakebay.net/documents/UFS_SBU_Expert_Panel_Draft_Report_Decision_Draft_FINAL_WQ_GIT_APPROVED_JUNE_9_2014.pdf Recommendations of the Expert Panel to Define Removal Rates for Urban Filter Strips and Stream Buffer Upgrade Practices]. Prepared by the Center for Watershed Protection, Elliott City, MD, for the Chesapeake Bay Program, Annapolis, MD. | *Battiata, J., S. Claggett, S. Crafton, D. Follansbee, D. Gasper, R. Greer, C. Hardman, T. Jordan, S. Stewart, A. Todd, R. Winston, and J. Zielinski, 2014. [http://www.chesapeakebay.net/documents/UFS_SBU_Expert_Panel_Draft_Report_Decision_Draft_FINAL_WQ_GIT_APPROVED_JUNE_9_2014.pdf Recommendations of the Expert Panel to Define Removal Rates for Urban Filter Strips and Stream Buffer Upgrade Practices]. Prepared by the Center for Watershed Protection, Elliott City, MD, for the Chesapeake Bay Program, Annapolis, MD. | ||

| − | *Virginia Department of Ecology, 1999. [ | + | *Virginia Department of Ecology, 1999. [https://www.deq.virginia.gov/water/stormwater/stormwater-construction/handbooks Virginia Stormwater Management Handbook]. First Edition, Volumes 1 and 2. Prepared by the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Division of Soil and Water Conservation, Richmond, VA. |

<noinclude> | <noinclude> | ||

Latest revision as of 14:19, 6 February 2023

Pretreatment vegetated filter strips, also sometimes called buffer strips or buffers, are sloped surfaces that rely on shallow (i.e., water level less than the height of the vegetation), distributed flow through dense vegetation to reduce flow velocity, allow particles to settle, and allow particle interception by the vegetation as their primary mechanism of pollutant removal. Properly designed, constructed, and maintained pretreatment vegetated filter strips reduce the sediment burden on full treatment practices (e.g. bioretention, constructed pond, etc.), thus improving the effectiveness and lifespan of full treatment practices. This page provides information on design, construction, and maintenance of pretreatment vegetated filter strips.

Contents

Design criteria

Contributing flow depth

To ensure compatibility with larger downstream, full-treatment best management practices (BMPs), contributing area size restrictions will be based on the site’s ability to achieve an acceptable flow depth to the pretreatment vegetated filter strip. To avoid flushing deposited sediment and flow channelization, the flow depth should remain no more than 1 inch and not result in knocking down the vegetation. The proper contributing flow depth to pretreatment vegetated filter strips can be attained either from direct runoff or by using level spreaders to distribute concentrated flow lateral (perpendicular and evenly) to the dominant flow path (to create sheet flow).

Contributing flow path to filter

The Tennessee Permanent Stormwater Management and Design Guidance Manual states: "Filter strips are used to treat very small drainage areas of a few acres or less. The limiting design factor is the length of flow directed to the filter. As a rule, flow tends to concentrate after 100 feet of flow length for impervious surfaces, and 150 feet for pervious surfaces. When flow concentrates, it moves too rapidly to be effectively treated by a Filter Strip, unless an engineered level spreader is used. When the existing flow at a site is concentrated, a grass channel or a water quality swale should be used instead of a Filter Strip (Lantin and Barrett, 2005)."

The State of Washington DOT recommends a maximum flow path of 75 feet.

Flow velocity

Attaining suitable flow velocities to the pretreatment vegetated filter strips is necessary to maintain the design sediment settling efficiencies, avoid flushing previously deposited sediments, and prevent erosion. To ensure that the pretreatment vegetated filter strip remains effective, contributing flow should not exceed 1 foot per second as it enters the pretreatment vegetated filter strip (Clar et al., 2004). This value is derived from calculating the maximum flow velocity suitable for the design recommendations of the pretreatment vegetated filter strip; assuming a depth of flow of 1 inch and a ryegrass slope of 6 percent. This provides the most conservative recommended velocity and will change as design characteristics change. To reduce flow velocity, incoming flow can be distributed over a wider width, shallower depth, and with a smaller velocity by installing a level spreader. Other protection against flow velocity, such as erosion control matting or other similar erosion controls, may be needed during vegetation establishment.

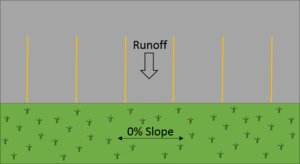

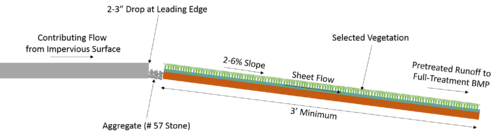

Achieving sheet flow

Inducing sheet flow that enters the pretreatment vegetated filter strip is critical to protecting and maintaining its effectiveness. As flow channelizes, it increases the erosive forces that both damage the vegetation as well as scour the soil, which leads to poor performance and failure. To achieve sheet flow, accurate grading of the contributing area must be completed during construction. Level spreaders can be used at sites where proper gradation cannot be achieved upstream of the filter strip or where the contributing flow is concentrated. A properly installed level spreader will dissipate the energy and ensure that sheet flow enters the pretreatment vegetated filter strip. The outflow of the level spreader should be 2 to 3 inches above the pretreatment vegetated filter strip to allow for sediment accumulation. Proper grading is also required for the pretreatment vegetated filter strip to avoid the possibility of the stormwater developing channelized flow. To achieve this, the filter strip must have a 0 degree lateral slope.

Filter strip dimensions

Pretreatment practices are designed to achieve at least a 25 percent reduction in sediment that enters the full-treatment BMP. To achieve this, while accounting for space requirements, pretreatment vegetated filter strips should be a minimum of 3 feet in length in the direction of flow. Variations in grain size distribution of sediment in the runoff water produces various removal efficiencies, but in a properly designed filter strip roughly 50 percent of the total suspended solids (TSS) settle out in the first 3 feet of a vegetated filter strip, meeting the goal of a 25 percent reduction in TSS (Lantin and Barrett, 2005). As the length of the pretreatment vegetated filter strip increases, so does the removal capacity of TSS, which indicates that the longest practical lengths for the site should be installed to achieve the most effective pretreatment. Filter strip width (the distance perpendicular to the flow) will vary depending on site sizing restrictions but must be large enough to meet the flow depth and velocity requirements.

Filter strip slope

Pretreatment vegetated filter strips require low slopes to achieve the necessary settling efficiencies to be effective. Lower slopes result in better settling efficiencies and reduced risk of channelized flows. An appropriate slope for a pretreatment vegetated filter strip is 2 to 6 percent. Whether from a level spreader or directly from an impervious area, allow a 2 to 3 inch fall in elevation at the inflow into a pretreatment vegetated filter strip to account for accumulated sediment. This lip may require erosion protection using erosion-control matting or similar controls during plant establishment.

Soils

Soil conditions need to be assessed at the site before the pretreatment vegetated filter strip is installed. Most soils are suitable for a pretreatment vegetated filter strip, but some soils may require amendments to support healthy vegetation development. Establishing vegetation is key to the success of the pretreatment vegetated filter strip because the vegetation provides the mechanism for pretreatment.

If the soil at a site is not deemed adequate to establish healthy vegetation, amending it with compost is an effective practice. Compost provides an effective organic amendment that will improve drainage, aeration, and nutrient balance. Soil amendments should be completed by adding 1 to 2 inches of well-decomposed compost to the top 6 to 8 inches of soil where the pretreatment vegetated filter strip will be installed. For more information on using compost as a soil amendment, see the University of Minnesota Extension webpage.

Vegetation

Various types of vegetation can be used successfully for a pretreatment vegetated filter strip. Factors that need to be considered include vegetation density, aesthetics, and cold climate suitability. Vegetation density is a major driving factor for the performance of the vegetated filter strips. Achieving at least 80 percent vegetation density (Barrett et al., 2004) is highly recommended to achieve adequate sediment-removal efficiencies. Using sod type grasses compared to bunch grasses is recommended, because bunch grasses may contribute to channelized flow. Filter strip appearance may be important to the site owner and should be tailored to their interests while maintaining the recommended design criteria. Pretreatment vegetated filter strips may be less effective during the winter (especially if snow-covered or frozen). Selecting a turf grass mix such as select fescues (tall and fine), ryegrass, and Kentucky bluegrass, which grow early in the spring and have some salt tolerance, will be critical to treating spring time snowmelt runoff as well as surviving increased salt concentrations. See the University of Minnesota Turfgrass Science website for more information. Establishing full and healthy vegetation will help prevent future additional maintenance.

Construction specifications

Pre-construction

After designing a pretreatment vegetated filter strip, considerations need to be taken before, during, and after the construction process. Before breaking ground, methods to achieve site easement and site protection must be planned.

Access agreements

Before starting construction, a site easement will need to be established in cases where the party that is installing the pretreatment vegetated filter strip needs access to land owned by another party. An easement is defined as “a non-possessory right to use and/or enter onto the real property of another without possessing it.” The easement can be temporary or permanent. Temporary easements are necessary when land that is needed for construction extends into another party’s land. Permanent easements are needed to establish authority to access the site for maintenance if crossing another party’s land is required to reach the pretreatment vegetated filter strip with maintenance equipment. An example of an access agreement can be located online here.

Site protection

Sediment- and erosion-control measures such as silt fences, are necessary to protect the downstream BMP from the construction site erosion, as well as protecting the construction site from receiving runoff. Sites that result in land disturbance of 1 acre or more that will result in a common plan of development or sale that disturbs more than 1 acre need to meet the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) and State Disposal System (SDS) Construction Stormwater General Permit. The permit describes the necessary sediment and erosion control practices at the site.

Construction

During construction, the ground must be stabilized, accurately graded, protected, and made suitable for healthy vegetation establishment.

Site erosion and sediment control

During construction, exposed soil will require soil stabilization and sediment-control measures. Erosion control is particularly important if the pretreatment vegetated filter strip is being installed upstream of an existing full-treatment BMP. If sediment is not contained within the construction boundaries, excess soil will clog the downstream BMP and require additional cleanup and maintenance. Measures that can be considered for soil stabilization include mulching and erosion-control blankets. When mulching is used, either straw or woodchips should be used while achieving at least 90 percent soil coverage. Erosion-control blankets and mulch are also used to provide structural stability to the soil during seed application to aid in vegetation establishment. For detailed construction site stabilization requirements, see the MPCA construction stormwater program page online.

Sediment-control measures will be used along with soil stabilization and includes BMPs such as silt fences, rock checks, bio rolls, drainage swales, and sediment traps. In addition to soil stabilization and sediment-control measures, managing soil stockpiles and sweeping tracked sediment on pavement near the construction site is required. If construction occurs in late summer to fall and is expected to carry into the winter, ensure that all of the exposed areas are covered before the first freeze. For more information on general erosion-control practices, see the Erosion Prevention Practices website.

Areas that will receive flows from impervious surfaces need to receive additional erosion-control protection to ensure that flows do not cause erosion while vegetation is being established. An aggregate of #57 stone with a depth of 3 to 4 inches North Carolina State Cooperative Extension Service, 2006 may be used at the leading edge or entrance to the filter strip as a buffer to slow flow velocity but should not be included in the vegetated filter strip length.

Grading

For pretreatment vegetated filter strips to be effective, the ground must be uniformly sloped perpendicular to the flow (i.e. zero lateral slope) to prevent channelization of runoff. This slope includes the slope upstream of the pretreatment vegetated filter strip (or installing a level spreader), as well as the pretreatment vegetated filter strip itself. During the grading process, efforts should be taken to minimize and reduce soil compaction to the best degree, as well as stabilizing any exposed soil. See the section on Site erosion and sediment control.

Compaction prevention and alleviation

To prevent soil compaction, ensure that no construction traffic occurs on the site of the pretreatment vegetated filter strip and that foot traffic is minimized as much as possible. Marking the boundaries of the pretreatment vegetated filter strip with paint and/or stakes can help keep away traffic. If compaction occurs or soil at the site is already compacted, measures can be used to alleviate the soil compaction. Methods indicated by the MPCA include soil ripping, scarifying, or mixing organic matter with the soil. These methods are often combined. For additional information, see the MPCA’s website.

Vegetation establishment

Establishing full and healthy vegetation is vital to ensuring that the pretreatment vegetated filter strip will perform as designed. For the best results, weeds should be removed from the bare soil before planting. To ensure that vegetation will become established and survive the winter freeze, a minimum of 60 days before the first expected frost should be allowed for the vegetation to grow. Soil stabilization practices such as erosion-control blankets should be used during vegetation establishment. To avoid damaging the emerging vegetation and causing site compaction, vehicle and foot traffic should not be allowed during the vegetation establishment phase. Achieving a minimum of 80 percent cover on the pretreatment vegetated filter strip, per the design guidelines, will ensure that the site is stabilized after construction. Following rain events, additional inspections and possible maintenance on the full-treatment BMP downstream of the pretreatment vegetated filter strip is recommended during the vegetation establishment phase.

Post-construction

After construction is completed, the boundary that marks the extents of the pretreatment vegetated filter strip must be maintained during vegetation establishment to keep away vehicle and foot traffic. Maintaining this boundary during vegetation establishment will prevent soil compaction and damage to the vegetation. Once the vegetation is fully established, the boundary can be removed, but foot traffic should still be minimized.

Operation and maintenance

Inspection and maintenance planning

To ensure that inspection and maintenance are conducted thoroughly and regularly, a plan that establishes maintenance responsibilities is required. Routine inspections and maintenance with specific guidelines of a pretreatment vegetated filter strip will help preserve its efficiency, extend its life, maintain aesthetics, and reduce the need for more expensive repairs.

The following are important post construction considerations.

- A site-specific plan should be established by the designer before constructing a pretreatment vegetated filter strip to include the following considerations:

- inspection checklists and schedule;

- routine maintenance checklists and schedule; and

- vegetation maintenance checklists and schedule.

- Establish a maintenance agreement between the practice owner and the local review authority that provides adequate access for the inspection, maintenance, and necessary equipment.

- While maintenance is being conducted, ensure that no heavy vehicle traffic occurs on the pretreatment vegetated filter strip and foot traffic is limited to avoid compaction.

- Avoid mowing when the ground is wet. Doing so can create rutting from the wheels.

- The pretreatment vegetated filter strip should not be used for permanent snow storage because this will extend the duration of ineffective treatment caused by increased snowpack.

Maintenance activities specifications and guidelines are provided below.

Inspection and maintenance frequency

Site inspection frequency varies based on the developmental stage of the vegetation. In the plant establishment period (first 2 years), regular inspections and maintenance include the following:

- bi-annual checks for any erosion/sediment buildup/vegetation loss/design issues;

- vegetation replacement after the first winter for any plant loss; and

- spring cleanup (stabilize erosion and clean out sediment and debris).

After the first 2 years, the pretreatment vegetated filter strip should operate as designed and require only annual inspections and inspections after storm events larger than the 10-year return period.

Inspections should be conducted starting at the leading edge at the upstream end of the pretreatment vegetated filter strip. This region will see the highest level of deposition of sediment as the stormwater runoff enters the pretreatment vegetated filter strip. After starting at the leading edge, progress downslope toward the full-treatment BMP.

A maintenance checklist is required to provide a record of inspections and maintenance conducted. A schedule of the frequency of inspection and maintenance is also required. An example of a maintenance checklist can be found online.

Maintenance activities

When inspections indicate that maintenance is necessary, the following sections provide guidelines to conduct the proper maintenance activities to restore the pretreatment vegetated filter strip to its design efficiency.

Removing sediment and debris buildup

As sediment is deposited after rain events, it can alter the uniform slope and result in channelized flow, which reduces the effectiveness of the pretreatment vegetated filter strip and can result in additional maintenance such as regrading and replanting. Removing sediment should occur when deposited sediment creates channelized flow through the pretreatment vegetated filter strip, sediment accumulation reaches the level of the contributing ground surface or level spreader, or when the sediment increases the water depth above the height the vegetation. Sediment removal should be completed by sweeping with a stiff bristle broom or using a vacuum truck. If a significant amount of sediment accumulates on the pretreatment vegetated filter strip (more than 2 inches) and is not removed in a timely manner, the vegetation will die off and require reseeding/replanting.

Along with removing sediment buildup, removing trash and debris is required in the maintenance process. Trash and debris buildup, like sediment buildup, can increase the chance of channelized flows, cause clogging in downstream pipe or intake structures, and negatively impact the aesthetics. If cleaning is not conducted, this trash and debris can be flushed into the full-treatment BMP during a larger rain event, which will reduce its effectiveness and result in a costlier cleanup.

Preventing or minimizing washouts and erosion of the pretreatment vegetated filter strip

To ensure that washout and erosion damage of the pretreatment vegetated filter strip does not occur, maintaining sufficient vegetation and a moderate slope per the design specifications is critical. Maintaining distribution of inflow (level spreader or otherwise), a slope of 6 percent or less, vegetation cover of at least 80 percent, and grass that is at least 3 inches long is recommended.

Maintaining vegetation

Maintaining adequate vegetation cover is critical to sustaining the design effectiveness and mitigating erosion of the pretreatment vegetated filter strip. As previously mentioned, a minimum of 80 percent vegetation and uniform cover is needed for the pretreatment vegetated filter strip to be effective.

Vegetation maintenance includes cleanup, mowing, invasive plant and weed removal, and quality checks. Cleanup, as mentioned above, requires removing excess sediment, debris, and trash. Large debris and trash can be removed by hand; smaller debris and sediment require sweeping with a stiff bristle broom or using a vacuum truck. To maintain the proper length for the vegetation, regular mowing must be conducted. Mowing should not be done when the ground is wet to reduce the chance of rutting from the wheels. The party in charge of mowing the pretreatment vegetated filter strip should be made aware that it is a BMP and that they should check for any signs of degradation (e.g., erosion, lack of vegetation) or need for additional maintenance. Mowing should be done as necessary to achieve grass heights of 3 to 4 inches. For additional mowing information, see the University of Minnesota website. Removing invasive plants and weeds will ensure that the planted vegetation remains healthy and full. Fertilizers should only be used in the vegetation establishment phase, because adding additional nutrients is counterproductive to using the pretreatment vegetated filter strip and permanent BMP. Establishing vegetation as quickly as possible and having healthy, dense vegetation is important.

Maintenance agreements

Maintenance agreements (similar to site easements) are required for one party to define and enforce maintenance by another party and may be necessary to access the site to conduct maintenance on the pretreatment vegetated filter strip. A maintenance agreement is a legally binding agreement between two parties and is defined as “a nonpossessory right to use and/or enter onto the real property of another without possessing it.” Maintenance agreements are often required for the issuance of a permit for constructing a stormwater management feature and are written and approved by legal counsel. These maintenance agreements can be established for a defined period of time and often define the types of inspections and maintenance that are required for the pretreatment vegetated filter strip. If maintenance needs to be conducted because the party in charge of the maintenance failed per the maintenance agreement, the party responsible for routine maintenance must follow the agreed-upon reimbursement terms. Examples of three site maintenance agreements can be found at this link.

References for vegetated filter strips

- Abu-Zreig, M., R. P. Rudra, M. N. Lalonde, H. R. Whiteley, and N. K. Kaushik, 2004. Experimental Investigation of Runoff Reduction and Sediment Removal by Vegetated Filter Strips. Hydrological Processes, Vol. 18, No. 11, pp. 2029–2037.

- Barrett, M. E.; P. M. Walsh; J. F. Malina, Jr.; R. J. Charbeneau, 1998. Performance of Vegetative Controls for Treating Highway Runoff. Journal of Environmental Engineering, Vol. 124, No. 11, pp. 1121–1128.

- Barret, M. E., A. Lantin, and S. Austrheim-Smith, 2004. Storm Water Pollutant Removal in Roadside Vegetated Buffer Strips. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 1890, No. 1, pp. 129-140.

- Blanco-Canqui, H., C. J. Gantzer, S. H. Anderson, and E. E. Alberts. 2004. Grass Barriers for Reduced Concentrated Flow Induced Soil and Nutrient Loss. Soil Science Society of America Journal, Vol. 68, No. 6, pp. 1963-1972.

- California Environmental Protection Agency, 2014. Draft Amendments to Statewide Water Quality Control Plans to Control Trash. Prepared by the California Environmental Protection Agency, Division of Water Quality, State Water Resources Control Board, Sacramento, CA.

- Clar, M. L., B. J. Barfield, and T. P. O’Connor, 2004. Stormwater Best Management Practice Design Guide Vegetative Biofilters. EPA/600/R-04/121A, prepared by the US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, National Risk Management Research Laboratory, Cincinnati, OH.

- Comprehensive Environmental Inc. and New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services, 2008. New Hampshire Stormwater Manual, Volume 2. Post-Construction Best Management Practices Selection & Design, prepared by Comprehensive Environmental Inc., Merrimack, NH, and the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services, Concord, NH.

- District Department of the Environment, 2013a. Stormwater Management Guidebook. Prepared by the District Department of the Environment, Washington, DC.

- District Department of Environment, 2013b. Anacostia River Watershed Trash TMDL Implementation Strategy. Prepared by the District Department of Environment, Stormwater Management Division, Washington, DC.

- Goel, P. K., R. P. Rudra, B. Gharabaghi, S. Das, and N. Gupta, 2004. Pollutants Removal by Vegetated Filter Strips Planted with Different Grasses. Proceedings, 2004 American Society of Association Executives/Canadian Society for Engineering in Agricultural, Food, and Biological Systems, Paper Number 042177, Fairmont Chateau Laurier, The Westin, Government Centre, Ottawa, ON, Canada, August 1–4.

- Gharabaghi, B., R. P. Rudra, H. R. Whiteley, and W. T. Dickinson, 2000. Sediment-Removal Efficiency of Vegetative Filter Strips. 2000 Annual Research Report, prepared by the Guelph Turfgrass Institute, Guelph, ON, Canada.

- Kayhanian, M., Suverkropp, C., Ruby, A., and Tsay, K. 2007. Characterization and Prediction of Highway Runoff Constituent Event Mean Concentration. Journal of Environmental Management, Vol. 85, No. 2, pp. 279–295.

- Lantin, A. and Barrett, M. 2005. Design and Pollutant Reduction of Vegetated Strips and Swales. Impacts of Global Climate Change, pp. 1-11.

- Maestre, A., and Pitt, R. 2005. The National Stormwater Quality Database, Version 1.1: A Compilation and Analysis of NPDES Stormwater Monitoring Information. Prepared for the US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water, Washington, DC.

- Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, 2008. Massachusetts Stormwater Handbook, Volume 2. Prepared by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, Boston, MA.

- Maniquiz-Redillas, M. C., F. K. Geronimo, and L. H. Kim, 2014. Investigation on the Effectiveness of Pretreatment in Stormwater Management Technologies. Journal of Environmental Sciences, Vol. 26, No. 9, pp. 1824–1830.

- North Carolina State Cooperative Extension Service, 2006. Level Spreaders: Overview, Design, and Maintenance. Prepared by Jon M. Hathaway and William F. Hunt, North Carolina State University.

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, 2014. NJ Stormwater Best Management Practices Manual. Chapter 9.10 Standard for Vegetative Filters, prepared by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Watershed Management, Trenton, NJ.

- Battiata, J., S. Claggett, S. Crafton, D. Follansbee, D. Gasper, R. Greer, C. Hardman, T. Jordan, S. Stewart, A. Todd, R. Winston, and J. Zielinski, 2014. Recommendations of the Expert Panel to Define Removal Rates for Urban Filter Strips and Stream Buffer Upgrade Practices. Prepared by the Center for Watershed Protection, Elliott City, MD, for the Chesapeake Bay Program, Annapolis, MD.

- Virginia Department of Ecology, 1999. Virginia Stormwater Management Handbook. First Edition, Volumes 1 and 2. Prepared by the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Division of Soil and Water Conservation, Richmond, VA.

Related pages

- Pretreatment selection tool

- Overview and methods of pretreatment

- Overviews for different types of pretreatment practices

- Information for specific types of pretreatment practices

- Design, construction, operation and maintenance specifications for pretreatment vegetated filter strips

- Pretreatment - Hydrodynamic separation devices

- Pretreatment - Screening and straining devices, including forebays

- Pretreatment - Above ground and below grade storage and settling devices

- Pretreatment - Filtration devices and practices

- Pretreatment - Other pretreatment water quality devices and practices

- To see the above pages as a single page, link here

Pretreatment sizing for basins and filters strips

Guidance for managing sediment and wastes collected by pretreatment practices

Tables

- Pretreatment tables - link to tabled information for pretreatment practices

- Hydrodynamic separator tables

- Screening and straining devices tables

- Above ground and below grade storage and settling tables

- Filtration tables

- Other water quality devices tables

Other information and links

This page was last edited on 6 February 2023, at 14:19.