Difference between revisions of "Process for selecting Best Management Practices"

m |

|||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

#Determine Any Site Restrictions and Setbacks. Check to see if any environmental resources or infrastructure are present that will influence where a BMP can be located at the development site. | #Determine Any Site Restrictions and Setbacks. Check to see if any environmental resources or infrastructure are present that will influence where a BMP can be located at the development site. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Investigate pollution prevention opportunities=== | ===Investigate pollution prevention opportunities=== | ||

[[Pollution prevention|Pollution prevention]] should be the first consideration during any development or redevelopment project and is the first step in the [[Using the treatment train approach to BMP selection|treatment train]]. This step involves looking for opportunities to reduce the exposure of soil and other pollutants to rainfall and possible runoff. Examples of pollution prevention practices include keeping urban surfaces clean, proper storage and handling of chemicals, and preventing exposure of unprotected soil and pollutants. | [[Pollution prevention|Pollution prevention]] should be the first consideration during any development or redevelopment project and is the first step in the [[Using the treatment train approach to BMP selection|treatment train]]. This step involves looking for opportunities to reduce the exposure of soil and other pollutants to rainfall and possible runoff. Examples of pollution prevention practices include keeping urban surfaces clean, proper storage and handling of chemicals, and preventing exposure of unprotected soil and pollutants. | ||

| Line 40: | Line 37: | ||

#'''Is the technique eligible for a possible stormwater credit?''' While all better site design techniques can reduce the size and cost of structural BMPs needed at the site, six techniques may be eligible as a stormwater credit during the design phase. Specific details on how stormwater credits are computed and reviewed are provided in Chapter 11. Check with your local review authority to see which credits may be offered in your community. Stormwater credits can reduce required water quality volumes by as much as 10% to 40%, and even more if multiple credits are applied. | #'''Is the technique eligible for a possible stormwater credit?''' While all better site design techniques can reduce the size and cost of structural BMPs needed at the site, six techniques may be eligible as a stormwater credit during the design phase. Specific details on how stormwater credits are computed and reviewed are provided in Chapter 11. Check with your local review authority to see which credits may be offered in your community. Stormwater credits can reduce required water quality volumes by as much as 10% to 40%, and even more if multiple credits are applied. | ||

#'''What are the potential cost savings for developers?''' Many BSD techniques can result in significant cost savings for developers during construction, in the form of reduced infrastructure costs, more available land for development, higher and faster sales, and lower long-term maintenance costs. Table 7.1 ranks the potential cost savings for each technique, as being high, medium, or low. | #'''What are the potential cost savings for developers?''' Many BSD techniques can result in significant cost savings for developers during construction, in the form of reduced infrastructure costs, more available land for development, higher and faster sales, and lower long-term maintenance costs. Table 7.1 ranks the potential cost savings for each technique, as being high, medium, or low. | ||

| − | #'''How easy is it to implement the technique in most communities?''' Some BSD techniques are standard practice in many communities, while others are newer and more difficult to adopt. | + | #'''How easy is it to implement the technique in most communities?''' Some BSD techniques are standard practice in many communities, while others are newer and more difficult to adopt. Some techniques are considered experimental and are not included in current local design guidelines and may involve a time-consuming and uncertain approval process. Required techniques are allowed under most local design guidelines; whereas promoted techniques are actively encouraged in most communities. Constrained techniques are harder to implement since current local codes impede or even prohibit their use in some communities. Designers should always check with their local reviewing authority to confirm which techniques can be used. |

| − | #'''What is the most appropriate land use for the technique?''' The nature of the proposed land use at a site often influences the kinds of BSD techniques can be applied. | + | #'''What is the most appropriate land use for the technique?''' The nature of the proposed land use at a site often influences the kinds of BSD techniques can be applied. Land uses include residential development, high density residential development, commercial/office including institutional uses, and industrial development. Some industrial developments are potential stormwater hotspot (PSH) and restrict the use of certain BMPs. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

All of the techniques shown in the table below are suitable for cold climate conditions in the State of Minnesota. | All of the techniques shown in the table below are suitable for cold climate conditions in the State of Minnesota. | ||

Revision as of 21:48, 3 January 2013

Designers need to carefully think through many factors to choose the most appropriate, effective and feasible practice(s) at a development site that will best meet local and state stormwater objectives. This chapter presents a flexible approach to BMP selection that allows a stormwater manager to select those BMPs most able to address an identified problem. Selecting an inappropriate best management practice (BMP) for a site could lead to adverse resource impacts, friction with regulators if a BMP does not work as anticipated, misperceptions about stormwater control success, and wasted time and money. Careful selection of BMPs will prevent negative impacts from installing the wrong BMP at the wrong location. Regulators can similarly use these matrices to check on the efficiency of proposed BMPs.

Contents

- 1 Using the Manual to Select BMPs

- 2 Factors to consider in selecting BMPs

- 2.1 Investigate pollution prevention opportunities

- 2.2 Design site to minimize runoff

- 2.3 Select temporary construction sediment control techniques

- 2.4 Identify receiving water issues

- 2.5 Identify climate and terrain factors

- 2.6 Evaluate stormwater treatment suitability

- 2.7 Assess physical feasibility at the site

- 2.8 Investigate Community and Environmental Factors

- 2.9 Determine any site restrictions and setbacks

- 3 Using Cost Factors to Select BMPs

- 4 References

Using the Manual to Select BMPs

The approach used in this Manual is slightly different from many other manuals. The proposed concept uses a “functional components approach” wherein basic BMP components are selected and pieced together to achieve a desired outcome. For example, if a BMP is needed to reduce peak discharge and remove sediment, the actual design components are then assembled based upon the material presented in the design guidance for stormwater ponds. In this case, a pond with a specific outflow rate(s) and sufficient water quality storage is designed to meet both functions according to state design criteria. This approach limits the inclusion of numerous individual BMP sheets in favor of categorical sheets with design variations included on each sheet. This should be a more user-friendly way of defining how BMPs can be designed to solve a particular problem.

BMP lists follow a simple-to-more complex treatment train sequence, one that starts with on-site pollution prevention and works upward in complexity to wetland systems. The list of treatment supplements is a compilation of additional measures that could be used to enhance treatment either before or after more complex BMP use.

Detailed BMP fact sheets can be found in the individual sections for bioretention, filtration (see swales or sand filters), infiltration (see Infiltration trench or Infiltration basin), ponds, wetlands, trees, green roofs, turf, and permeable pavement. Pollution prevention, better site design/LID, runoff minimization (see Stormwater re-use and rainwater harvesting) and temporary construction runoff control practices will include some descriptive language for the numerous practices listed via “fact sheets,” but will not contain engineering details. Sections on treatment supplements will similarly not contain detailed engineering, but will describe a process that designers should follow when considering the use of proprietary devices, inserts and chemical/biological treatment.

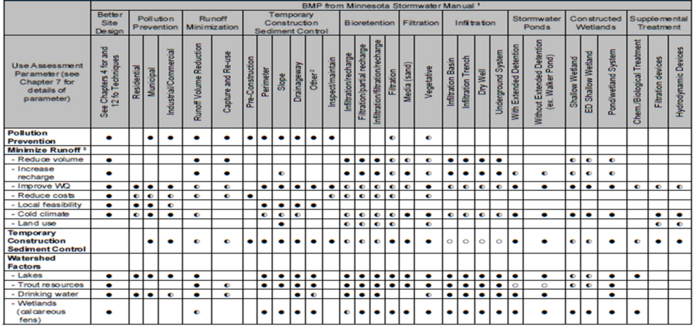

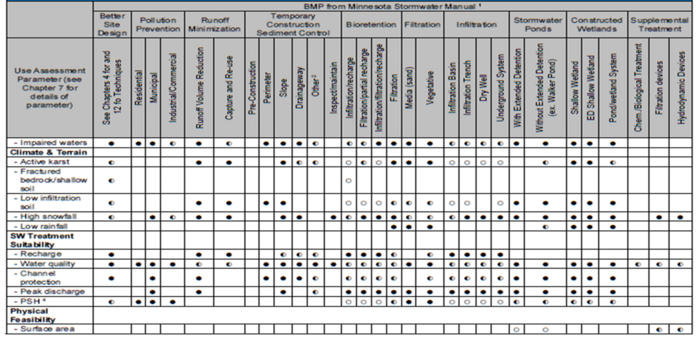

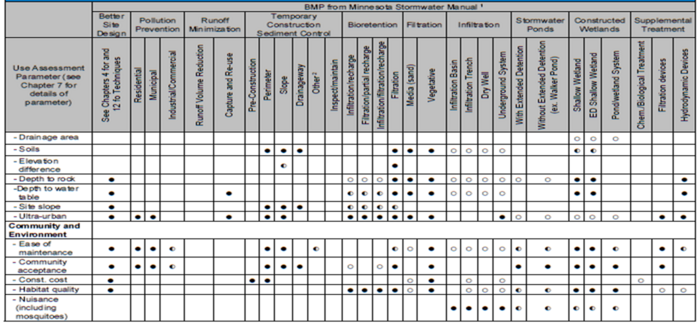

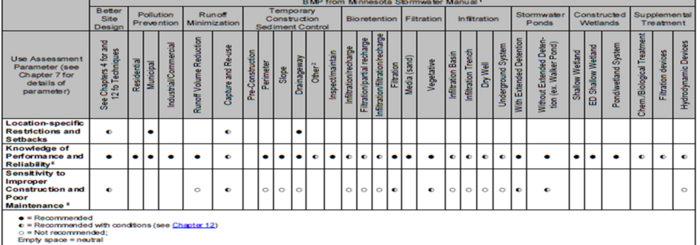

The beginning stormwater manager or a designer unfamiliar with the many BMPs available might have some questions on which BMP or group of BMPs to include in a treatment scheme. The figure below is a screening tool to get the user going on BMP selection. It contains the list of BMPs contained in this Manual and a corresponding list of use assessment parameters to help narrow the wide range of potential BMPs for a particular project. A user will need to have some objectives in mind to extract information from the matrix, but once into the matrix, selection of BMPs based on either positive or negative factors will be possible.

Factors to consider in selecting BMPs

Nine factors should be evaluated in the BMP selection process, as follows:

- Investigate Pollution Prevention Opportunities. Evaluate the site to look for opportunities to prevent pollution sources on the land from becoming mobilized by runoff.

- Design Site to Minimize Runoff. Assess whether any better site design techniques can be applied at the site to minimize runoff and therefore reduce the size of structural BMPs.

- Select Temporary Construction Sediment Control Techniques. Check to see what set of temporary sediment control techniques will prevent erosion and minimize site disturbance during construction.

- Identify Receiving Water Issues. Understand the regulatory status of the receiving water to which the site drains. Depending on the nature of the receiving water, certain BMPs may be promoted, restricted or prohibited, or special design or sizing criteria may apply.

- Identify Climate and Terrain Factors. Climate and terrain conditions vary widely across the state, and designers need to explicitly consider how each regional factor will influence the BMPs proposed for the site.

- Evaluate Stormwater Treatment Suitability. Not all BMPs work over the wide range of storm events that need to be managed at the site, so designers need to choose the type or combination of BMPs that will provide the desired level of treatment.

- Assess Physical Feasibility at the Site. Each development site has many physical constraints that influence the feasibility of different kinds of BMPs; designers confirm feasibility by assessing eight physical factors at the site.

- Investigate Community and Environmental Factors. Each group of BMPs provides different economic, community, and environmental benefits and drawbacks; designers need to carefully weigh these factors when choosing BMPs for the site.

- Determine Any Site Restrictions and Setbacks. Check to see if any environmental resources or infrastructure are present that will influence where a BMP can be located at the development site.

Investigate pollution prevention opportunities

Pollution prevention should be the first consideration during any development or redevelopment project and is the first step in the treatment train. This step involves looking for opportunities to reduce the exposure of soil and other pollutants to rainfall and possible runoff. Examples of pollution prevention practices include keeping urban surfaces clean, proper storage and handling of chemicals, and preventing exposure of unprotected soil and pollutants.

Design site to minimize runoff

A range of better site design (BSD) techniques can provide non-structural stormwater treatment, improve water quality and reduce the generation of stormwater runoff. These techniques reduce impervious cover and reduce the volume of stormwater runoff at a site, which can save space and reduce the cost of structural BMPs. Designers should understand the comparative benefits and drawbacks of BSD techniques that could potentially be applied to the site. Designers should answer the following questions:

- How well does the technique reduce stormwater runoff volume? Each BSD technique is rated as having a high, medium, or low capability to reduce the volume of stormwater runoff generated at a development site. The ability to promote infiltration of runoff, preserve natural hydrology or filter pollutants are main reasons why these techniques vary in their volume reduction capability.

- Is the technique eligible for a possible stormwater credit? While all better site design techniques can reduce the size and cost of structural BMPs needed at the site, six techniques may be eligible as a stormwater credit during the design phase. Specific details on how stormwater credits are computed and reviewed are provided in Chapter 11. Check with your local review authority to see which credits may be offered in your community. Stormwater credits can reduce required water quality volumes by as much as 10% to 40%, and even more if multiple credits are applied.

- What are the potential cost savings for developers? Many BSD techniques can result in significant cost savings for developers during construction, in the form of reduced infrastructure costs, more available land for development, higher and faster sales, and lower long-term maintenance costs. Table 7.1 ranks the potential cost savings for each technique, as being high, medium, or low.

- How easy is it to implement the technique in most communities? Some BSD techniques are standard practice in many communities, while others are newer and more difficult to adopt. Some techniques are considered experimental and are not included in current local design guidelines and may involve a time-consuming and uncertain approval process. Required techniques are allowed under most local design guidelines; whereas promoted techniques are actively encouraged in most communities. Constrained techniques are harder to implement since current local codes impede or even prohibit their use in some communities. Designers should always check with their local reviewing authority to confirm which techniques can be used.

- What is the most appropriate land use for the technique? The nature of the proposed land use at a site often influences the kinds of BSD techniques can be applied. Land uses include residential development, high density residential development, commercial/office including institutional uses, and industrial development. Some industrial developments are potential stormwater hotspot (PSH) and restrict the use of certain BMPs.

All of the techniques shown in the table below are suitable for cold climate conditions in the State of Minnesota.

This table shows an overview of techniques to reduce runoff during site design and layout

Link to this table

| Better site design technique | Reduce stormwater runoff volume | Possible stormwater credit | Cost savings | Local feasibilitya | Appropriate land use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural area conservation | High | Yes | High | Promoted | All |

| Site reforestation and prairie restoration | High | Yes | Medium | Promoted | All |

| Stream and shoreline buffers | High | Yes | High | Required | All |

| Soil amendments | High | Yes | Low | Experimental | All |

| Surface impervious cover disconnection | High | yes | High | Experimental | Residential, commercial, industrial; caution with industrial potential stormwater hotspots |

| Rooftop disconnection | High | Yes | High | Experimental | All |

| Open space design | High | No | High | Constrained | Residential, commercial, industrial |

| Grass channels | Low | Yes | High | Constrained | Residential, commercial, industrial; caution with industrial potential stormwater hotspots |

| Reduced street width | High | No | High | Constrained | Residential, commercial |

| Reduced sidewalks | High | No | High | Constrained | Residential, commercial |

| Smaller and vegetated cul-de-sac | High | No | High | Constrained | Residential |

| Shorter driveways | High | No | High | Constrained | Residential |

| Green parking lots | Medium | No | Low | Experimental | High density residential, commercial, industrial |

avaries greatly among communities; consult local reviewing authority to determine ease of implementation

Select temporary construction sediment control techniques

Construction sites can be a major source of sediment and nonpoint source pollutants if soils are exposed to erosion. Effective application of temporary sediment controls is an essential element of a stormwater management plan and helps preserve the long-term capacity and function of permanent stormwater BMPs. Designers should recognize that they will need to revisit and refine the erosion and sediment control plan throughout the design and construction period as more information on site layout and the type and location of BMPs becomes available.

This table shows a summary of temporary construction and sediment control techniques

Link to this table

| Technique | Practice | How it works | When to apply | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-construction planning | Site planning and grading | Minimizes soil disturbance and unprotected exposure | Planning | Expose only as much as needed for immediate construction |

| Sequencing | Limits amount of soil exposed | Planning | ||

| Resource protection | Forest conservation and water resource buffers | Establishes protective zone around valued natural resources | Early | Buffer variable from a few feet to 100 feet depending uopn resource being protected and local regulations |

| Perimeter control | Access and egress control | Minimizes transport of soil off-site | Early | Must be in place prior to commencement of construction activities |

| Inlet protection | Stops movement of soil into drainage collection system | Early | ||

| Slope stabilization | Grade breaks | Minimizes rill and gully erosion | Early | No unbroken slopes > 75 feet on 3:1 side slopes or greater |

| Silt curtain | Stops sediment from moving | Early | ||

| Runoff control | Stabilize drainageways | Minimizes increased erosion from channels | All construction phases | Possible to convert these into permanent open channel systems after construction |

| Sediment control basins | Collects sediment that erodes from site before it leaves site or impacts resource | All construction phases | Possible to convert these into post construction practices after construction | |

| Rapid stabilization of exposed soils | Seeding and mulch | Immediately established vegetative cover on exposed spoil | All construction phases | Apply seed as soils are exposed |

| Blankets | Provides extra protection for exposed oil or steep slopes | All construction phases | Apply blanket as exposed soil cover until plants established | |

| Inspection and maintenance | Formalized I&M program | Assures that BMPs are properly installed and operating in anticipated manner | All construction phases | Essential to proper BMP implementation |

Identify receiving water issues

Designers should understand the nature and regulatory status of the waters that will receive runoff from the development site. The type of receiving water strongly influences the preferred BMP to use, and in some cases, may trigger increased treatment requirements. There are many different kinds of Special Waters and other sensitive receiving waters in Minnesota that should be considered (see Sensitive waters and other receiving waters; Regulatory information). For purposes of this Manual, receiving waters fall into five categories: lakes, trout resources, drinking waters, wetlands and impaired waters.

The full spectrum of BMPs can be applied to sites that drain to receiving waters that are not designated as special or sensitive in Minnesota. If the receiving water falls into one of the special or sensitive water categories, the range of BMPs that can be used may be reduced. For example, only BMPs that provide a higher level of phosphorus removal may be encouraged for sensitive lakes. In trout streams, use of ponds may be discouraged due to concerns over stream warming.

- Does the site drain to a sensitive lake? BMPs differ in their ability to remove phosphorus, which is the key stormwater pollutant managed to protect sensitive lakes (Note: this category also includes trout lakes and surface water drinking supplies). Communities may require greater water quality treatment, a specific phosphorus removal rate or even load reduction at the development site to protect their most sensitive lakes. In general, higher phosphorus removal requirements result in shorter list of acceptable BMP designs that can be used at the site.

- Does the site drain to a trout stream protection? Trout streams merit special protection, which strongly influences the choice of BMPs. Some BMPs are preferred because they promote baseflow, protect channels from erosion or achieve high rates of sediment removal. Other BMPs, such as ponds, may be discouraged because they cause stream warming.

- Is the site within a ground water drinking water source area? Sites located in aquifers used for drinking water supply require BMPs that can recharge aquifers at the same time they prevent ground water contamination from polluted stormwater, particularly when it is generated from potential stormwater hotspots (PSH).

- Does the site drain to a wetland? Wetlands can be indirectly impacted by upland development sites, so designers should choose BMPs that can maintain wetland hydroperiods and limit phosphorus loads. Several BMPs provide infiltration and extended detention storage that protect natural wetlands from increased stormwater runoff and nutrient loads from upland development.

- Does the site drain to an “impaired water”? BMP selection becomes very important when a development site drains to a receiving water that is not meeting water quality standards and is subject to a TMDL. The designer may need to choose BMPs that achieve a more stringent level of removal for the listed pollutant(s) of concern.

The full range of BMP restrictions for the five categories of receiving water are presented in the following table.

This table shows the appropriateness of different BMP groups for different categories of receiving water.

Link to this table

| BMP group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lakes | Trout resources | Drinking waterb | Wetlandsc | Impaired waters | |

| General location | Outside of shoreline buffer | Outside of stream buffer | Setbacks from wells, septic systems | Outside of wetland buffer | Selection based on pollutant removal for target pollutants |

| Bioretention | Preferred | Preferred | OK with cautions for potential stormwater hotspots | Preferred | Preferred |

| Filtration | Some variations restricted due to limited P removal; combined with other treatments | Preferred | Preferred | OK | Preferred |

| Infiltration | Preferred | Preferred | Restricted if potential stormwater hotspot | Preferred | Restricted for some target TMDL pollutants |

| Stormwater ponds | Preferred | Some variations restricted due to pool and stream warming concerns | Preferred | Preferred but no use of natural wetlands | Preferred |

| Constructed wetlands | Some variations restricted due to seasonally variable P removal; combined with other treatments | Restricted except for wooded wetlands | Preferred | Preferred but no use of natural wetlands | Preferred |

| Supplemental BMPs | Restricted due to poor P removal; must combine with other treatmentsX | Restricted - must combine with other treatments | Restricted - must combine with other treatments | Restricted - must combine with other treatments | Restricted - must combine with other treatments |

aOutstanding Resource Value Waters (ORVWs) are not included because they fall within one of the receiving water management categories.

bApplies to groundwater drinking water source areas only. Use the sensitive lakes category to define BMP design restrictions for surface water drinking supplies.

cIncluding calcareous fens

Identify climate and terrain factors

Climate and terrain conditions vary widely across the State, and designers need to explicitly consider each of these regional factors in the context of BMP selection (see also Chapter 2 and Appendix A). The proposed BMPs for the site should match the prevailing climate and terrain; preferred BMPs and design modifications are outlined in Table 7.6.

- Is the site within an active karst region? Active karst is defined as karst features within 50 feet of the surface of the site and poses many challenges to BMP design. It is safe to assume that any treated or untreated runoff that is infiltrated will reach the drinking water supply in karst areas. In addition, some BMPs can promote sinkhole formation that may threaten the integrity of the practice. Table 7.6 reviews the most feasible BMPs in active karst regions, and the type of geotechnical investigations needed. Reference is also made to a Chapter 13 discussion of karst features.

- Does the site have exposed bedrock or shallow soils? Portions of the State have exposed bedrock or extremely shallow soils that may preclude the use of some BMPs. For example, infiltration practices may be impractical in shallow soils due to the limited soil separation distance between the bottom of the practice and bedrock. Other BMPs, such as ponds and wetlands may be feasible, but may be more difficult or costly to design and construct (e.g., may require liners to prevent rapid drawdown).

- Will the site experience high snowfall or require melt water treatment? Table 7.6 presents guidance on how to choose BMPs for high snowfall areas that can withstand snow and ice cover (consult Figure 2.5 in Chapter 2 to check if your development site is within this zone). Frozen conditions will inhibit performance throughout the winter and generate a significant volume of melt water and pollutant loads in the spring.

- Is the site located in a region with low annual rainfall? Development sites in the southwest part of the State get much less annual rainfall, which plays a strong role in BMP selection. Frequent rainfall is often important to maintain water balance in ponds and wetlands. BMP function could decline when there is not enough runoff to sustain a normal pool elevation.

Evaluate stormwater treatment suitability

Not all BMPs work over the wide range of storm events that need to be managed at a site. Designers first need to determine which of the recommended unified sizing criteria apply to the development site (i.e., recharge, water quality, channel protection, peak discharge), and then choose the type or combination of BMPs from Table 7.7 that can achieve them.

This is the stage in BMP selection process where designers often find that a single BMP may not satisfy all stormwater treatment requirements. The alternative is to use a combination of BMPs arranged in a series or treatment train, or add supplemental practices to the primary BMP that provide additional pre- or post-treatment.

- Can the BMP provide ground water recharge? BMPs that infiltrate runoff into the soil are needed when a site is subject to a recharge requirement. If infiltration is impractical, designers may want to use some of the better site design techniques profiled in Table 7.1 to make up the difference and provide full treatment.

- Can the BMP treat the water quality volume? All of the BMPs in this Manual, with the exception of supplemental BMPs, can meet the water quality volume (Vwq) requirement stipulated in construction general permit, so this is seldom a major factor in BMP selection.

- Can the BMP provide channel protection? BMPs must provide extended detention for long periods at sites where channel protection (Vcp) is required to protect streams, which means that only a short list of BMPs can meet this criterion (see Table 7.7). BMPs that cannot meet the channel protection requirement as stand alone practices should not be discarded, as they may still be needed to meet other sizing criteria (e.g., water quality).

- Can the BMP effectively control peak discharges from overbank floods? Generally, only ponds, wetlands and infiltration basins have the capacity to control peak discharge events that cause flooding at the site (e.g., Vp10 and Vp100 storm events). Once again, if a BMP cannot meet peak discharge requirements, it can be used in combination with one that does to meet all sizing criteria.

- Can the BMP accept runoff from potential stormwater hotspots (PSHs)? Designers need to be careful choosing BMPs at sites designated as PSHs to minimize the risk of ground water contamination. BMPs that rely on infiltration should be avoided and other design modifications may be needed for other practices that send runoff into the soil (Table 7.7).

Assess physical feasibility at the site

By this point, the list of possible BMPs has been narrowed and now physical factors at the site are assessed to whittle it down even further. Table 7.8 indicates eight physical factors at the site that can constrain, restrict or eliminate BMPs from further consideration.

- Is there enough space available for the BMP at the site? BMPs vary widely in the amount of surface area of the site they consume, which can be an important factor at intensively developed sites where space may be limiting and land prices are at a premium. In some instances, underground BMPs may be an attractive option in highly urban areas. Some general rules of thumb on BMP surface area needs are presented in Table 7.8, expressed in terms of contributing impervious area or total area.

- Is the drainage area at the site suitable for the proposed BMP? Table 7.8 shows the minimum or maximum recommended drainage areas for each group of BMPs. If the drainage area of the site exceeds the maximum, designers can always use multiple smaller BMPs of the same type, or modify the design. The minimum drainage area thresholds for ponds and wetlands are not quite as flexible, although smaller drainage areas can work if designers can confirm the presence of ground water or baseflow that can sustain a normal pool and incorporate design features to prevent clogging.

- Will soils limit BMP options at the site? Low infiltration rates limit or preclude the use of infiltration practices and certain kinds of bioretention designs. By contrast, soils with low infiltration rates are preferred for ponds and wetlands since they help to maintain permanent pools without need for a liner. Designers should consult the design guidance in Chapter 12 to determine minimum soil infiltration rates and testing procedures for each kind of BMP. Table 7.8 references USDA-NRCS Hydrologic Soil Groups A to D. Further geotechnical testing may be needed to confirm soil permeability and ground water depth.

- Is enough head present at the site to drive the BMP? Head is defined as the elevation difference between the inflow and outflow point of a BMP that enables gravity to drive the BMP. BMP choices are constrained at flatter sites that have less than three or four feet of available head.

- Will depth to bedrock or the water table constrain the proposed BMP? Bioretention, infiltration and some filtering practices need a minimum separation distance from the bottom of the practice to bedrock (or the water table) to function properly. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency’s Construction General Permit (CGP) requires a minimum distance of three feet between the bottom of an infiltrating BMP and the seasonally saturated water table. Other BMPs do not require as much separation distance, although the cost and complexity of construction of most BMPs increases sharply at development sites where the bedrock or water table are close to the surface.

- Is the slope at the proposed BMP site a design constraint? Sites with extremely steep slopes can make it hard to locate suitable areas for BMPs. Table 7.8 outlines maximum slope recommendations for BMPs, which refers to the gradient where the BMP will actually be installed. Designers will need to carefully scrutinize site topographic and grading plans to find suitable locations, and if this does not work, the grading plan may need to be changed to meet slope thresholds.

- Is the BMP suitable for ultra-urban sites? BMP selection for ultra-urban development and redevelopment sites is challenging, since space is extremely limited, land is expensive, soils are disturbed, and runoff volumes and pollutant loadings are great. These sites do, however, present a great opportunity for making progress in stormwater management where it has not previously existed. Table 7.8 compares the general suitability of BMPs for ultra-urban sites.

Investigate Community and Environmental Factors

Some BMPs can provide positive economic and environmental benefits for the community, while others can have drawbacks or create nuisances. Table 7.9 presents general guidance on how to choose the most economically and environmentally sustainable BMPs for the community. Readers should note that rankings in this table are fairly subjective, and may vary according to community perceptions and values. A poor score should not mean the BMP is discarded; rather, it signals that attention should be focused on improving that element of the BMP during the design phase.

- Ease of Maintenance. All BMPs require routine inspection and maintenance throughout their life cycle, although some are easier to maintain than others. This screening factor looks at each major BMP from the standpoint of the frequency and cost of scheduled maintenance, chronic maintenance problems, reported failure rates, and inspection needs. Designers should try to prevent or reduce maintenance problems during the design phase for BMPs that are rated as difficult to maintain.

- Community Acceptance. Community acceptance involves a great deal of subjective perception, but a general sense can be gleaned from market surveys, reported nuisance problems, visual preference, and vegetative management. BMPs rated as having low or medium community acceptance can often be improved through better landscaping or more creative design. Note that while underground BMPs enjoy high community acceptance, this is solely due to the fact they are “out of sight, out of mind,” which substantially reduces their ease of maintenance.

- Construction Cost. Table 7.9 presents a very general comparison of BMP construction costs, based on the average cost per impervious acre treated. More specific techniques to estimate construction and O&M costs for individual BMPs are provided in Chapter 6, Chapter 12, and Appendix D.

- Habitat Quality. BMPs have the potential to create aquatic and terrestrial habitat for wildlife and waterfowl, which can be an important community amenity. Potential habitat quality is ranked as low, medium or high depending on BMP-specific factors such as surface area, water and wetland features, vegetative cover, and buffers. Habitat quality is not automatic, and requires proper installation, landscaping, and vegetative management at the BMP.

- Nuisances. Nearly all BMPs can create nuisance conditions, particularly if they are poorly designed or maintained. BMP nuisances reduce community acceptance and generate complaints, but seldom affect the pollutant removal performance of the BMP. Common nuisances include mosquitoes, geese, overgrown vegetation, floatable debris and odors. A more expanded discussion on design considerations to manage mosquitoes is provided in Chapter 6. If a BMP is prone to nuisance conditions, designers should focus attention on preventing or minimizing the problem. For example, distance to residences could be a factor in determining the impact of mosquito breeding, so an analysis of BMP placement relative to residences could result in some impact mitigation.

Determine any site restrictions and setbacks

The last step in BMP selection checks to see if any environmental resources or infrastructure are present that will influence where a BMP can be located on the site (i.e., setback or similar restriction). Table 7.10 presents an overview of ten site-specific conditions that impact where a BMP can be located on a site. A more extensive discussion of the relevant Minnesota rules and regulations that influence BMP design can be found in Chapter 5 and Appendix G.

Using Cost Factors to Select BMPs

Stormwater managers are reluctant to make a final BMP selection without having some basic information on the construction and maintenance costs. Chapter 12 and Appendix D contain guidance on the preparation of construction and maintenance costs for specific BMPs. However, this technique is not always practical or even feasible at the BMP selection stage. Stormwater managers who wish to learn the relative cost effectiveness between two specific BMPs are encouraged to use information prepared by the Minnesota Department of Transportation in a May, 2005 report titled The Cost Effectiveness of Stormwater Management Practices. As part of their research, the authors incorporated both historical construction costs and 20 years of expected annual maintenance costs. The result is a series of graphs that present total present cost (construction plus maintenance) plotted against water quality volume. Figure 6.2 can be used to determine the total present worth value of construction plus maintenance costs for wet basins. Similar graphs are available for dry detention basins, constructed wetlands, infiltration trenches, bioinfiltration filters, sand filters, and 1,000-foot long vegetated swales in the Mn/DOT report. This simple technique can then be used to estimate the total present cost of a BMP under consideration. For purposes of establishing a specific budget for construction and maintenance, stormwater managers are encouraged to follow the procedures outlined in Chapter 12.

References

- Caraco, D. 2001. Managing Phosphorus Inputs Into Lakes III: Evaluating the Impact of Watershed Treatment. Watershed Protection Techniques. 3 (4): 791-796. Center for Watershed Protection. Ellicott City, MD.

- Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE). 2000. 2000 Maryland Stormwater Design Manual. MDE. Baltimore, MD.

- Walker Jr., W. W., 2000. P8 Urban Catchment Modal (Version 2.4), IEP, Inc. and Narrangansett Bay Project USEPA/RIDEM. wwwalker.net/p8/

- Winer, R. 2000. National Pollutant Removal Performance Database for Stormwater Treatment Practices. 2nd Edition. Center for Watershed Protection. Ellicott City, MD.