Technical guidance used by MPCA to develop guidelines for setting TMDL WLAs for regulated stormwater

Successful implementation of stormwater requirements in a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) requires integration of three components:

- The permit must contain language that links the TMDL language to Stormwater Pollution Prevention Program (SWPPP) requirements.

- There must be a procedure for incorporating TMDL requirements into the SWPPP.

- A TMDL must contain clear language that can be linked to the permit and SWPPP.

The following document provides a discussion of issues related to setting wasteload allocations for permitted stormwater and to implementing activities to address a stormwater wasteload allocation. Several recommendations are presented. In some cases, these recommendations are developed as policy to be implemented in developing TMDLs that include a stormwater component.

Contents

- 1 Stormwater program

- 2 Permit language for impaired waters

- 3 TMDL stormwater issues

- 3.1 General information about TMDLs

- 3.2 Setting wasteload allocations (WLAs)

- 3.2.1 Construction stormwater

- 3.2.2 Municipal stormwater

- 3.2.3 Industrial stormwater

- 3.2.4 Individual permits

- 3.2.5 Choosing categorical or individual WLAs and the form of the WLA

- 3.2.6 Adjusting WLAs

- 3.2.7 Accounting for future growth

- 3.2.8 WLAs for permitted MS4s and LAs for non-permitted MS4s

- 3.2.9 Recommendations

- 3.3 Implementation

- 3.4 Other issues

- 4 Summary of recommended policy

- 5 Case studies - Construction stormwater WLAs

- 6 Case studies - Municipal stormwater WLAs

- 7 Case studies - Industrial stormwater WLAs

- 8 Case studies - Future growth

- 9 Case studies - Implementation

- 10 Case studies - Monitoring

- 11 Case studies - Reasonable assurances

- 12 Case studies - Surrogates

Stormwater program

The Federal National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) was mandated by Congress under the Clean Water Act. Many activities are regulated under the NPDES Program, including confined animal feeding operations (CAFO), combined sewer overflows (CSO), sanitary sewer overflows (SSO), and stormwater. Stormwater can further be divided into three permit areas – construction activities, industrial activities, and municipal activities. Minnesota regulates the disposal of stormwater through State Disposal System (SDS) permits. The MPCA issues combined NPDES/SDS permits for construction sites, industrial facilities and municipal separate storm sewer systems (MS4s).

Each of the three stormwater permitting programs has a general permit. Individual permits may also be issued within each program.

Under the Phase I construction permit, operators of large construction activity resulting in the disturbance of five or more acres of land are required to obtain general permit coverage. Phase II includes small construction activity that results in the disturbance of equal to or greater than one acre, or less than one acre if that activity is part of a "larger common plan of development or sale". Owners and operators of projects meeting the above criteria must obtain permit coverage and implement practices to minimize pollutant runoff from construction sites. Permits may also be required for activity disturbing less than one acre but deemed by MPCA to represent a risk to water resources. The current general construction permit was issued August 1, 2003. The construction permit is applied statewide, except for Tribal areas. For example, some feedlot activities require permit coverage. For more information, see [1].

Public and private operators of industrial facilities included in one of the 11 categories of industrial activity defined in the federal regulations by an industry's Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code or a narrative description of the activity found at the industrial site are required to apply for a permit. A facility may be eligible for a conditional no-exposure exclusion from permitting provided their industrial materials and activities are entirely sheltered from storm water. The federal regulations can be found at 40 CFR 122.26 (b)(14)(i)-(xi). For more information, see [2].

A municipal separate storm sewer system is a conveyance or system of conveyances (roads with drainage systems, municipal streets, catch basins, curbs, gutters, ditches, man-made channels, storm drains):

- Owned or operated by a state, city, town, borough, county, parish, district, association, or other public body (created by or pursuant to State law) having jurisdiction over disposal of sewage, industrial wastes, stormwater, or other wastes, including special districts under State law such as a sewer district, flood control district or drainage districts, or similar entity, or an Indian tribe or an authorized Indian tribal organization, or a designated and approved management agency under section 208 of the federal Clean Water Act, United States Code, title 33, section 1288, that discharges to waters of the United States;

- Designed or used for collecting or conveying stormwater;

- Which is not a combined sewer; and

- That is not part of a publicly owned treatment works.

Not all MS4s require permit coverage. The cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul are Phase 1 permittees and require individual permits. The remaining regulated MS4s are Phase 2 permittees and are either mandatory or designated. Mandatory MS4s occur in urbanized areas as defined by the 2010 Census. An "urbanized area" is a land area comprising one or more places (“central places”) and the adjacent densely settled surrounding area (“urban fringe”) that together have a residential population of at least 50,000 and a density of at least 1,000 people per square mile. The definition also includes any other public storm sewer system located fully or partially within an urbanized area. For example, the University of Minnesota Twin City campus is a mandatory MS4 because it operates a conveyance system and is part of an urban area. There are 212 mandatory MS4s in eight urban areas in Minnesota.

MS4s outside of urbanized areas that have been designated by the MPCA for permit coverage include cities and townships with a population of at least 10,000 and cities and townships with a population of at least 5,000 and discharging or the potential to discharge to valuable or polluted waters. These designated MS4s are required to obtain permit coverage by February 15, 2007. For more information see [3].

Permit language for impaired waters

Although this document focuses on TMDL language, it is important to understand permit language that pertains to impaired waters and TMDLs. TMDL language must be written in a manner that is consistent with permit language and requirements. This section provides a summary of permit language. Permits can be found on MPCA’s Stormwater website ([4]).

Construction stormwater

The 2013 construction general permit contains language that addresses impaired waters for which TMDLs have or have not been completed and approved by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). The permit can be found at [5].

WLAs for construction stormwater should be determined when the pollutant or stressor for the impairment is phosphorus (nutrient eutrophication biological indicators), turbidity, dissolved oxygen, or biotic impairment (fish bioassessment, aquatic plant bioassessment and aquatic macroinvertebrate bioassessment). Construction activities that occur within one mile of an impaired water must comply with the additional BMPs described in Appendix A of the permit. This requirement exists for impaired waters with or without a US EPA-approved WLA for construction stormwater. If a US EPA-approved TMDL contains a WLA for construction stormwater and the TMDL describes additional BMPs needed to meet the TMDL, then the permittee must comply with these additional BMPs. The additional requirements can be extended beyond the one mile distance.

Municipal stormwater

The 2013 issuance of the municipal (MS4) permit provides language for discharges to impaired waters with a USEPA-Approved TMDL that includes an applicable WLA. The MS4 permit requires a Stormwater Pollution Prevention Program (SWPPP). As a part of the SWPPP document, permittees are required to address all WLAs in TMDLs approved prior to the effective date of the permit (August 1, 2013). In doing so, they must determine if they are currently meeting their WLA(s). If the WLA is not being achieved at the time of application, a compliance schedule is required that includes interim milestones, expressed as best management practices (BMPs), that will be implemented over the current five-year permit term to reduce loading of the pollutant of concern in the TMDL. Additionally, a long-term implementation strategy and target date for fully meeting the WLA must be included.

The permit also contains language requiring permittees to demonstrate continuing progress toward meeting each applicable WLA approved prior to the effective date of the permit. This will come in the form of annual reporting on the interim milestones described in the compliance schedule of the SWPPP application. The report will be completed on a form provided by the commissioner and include the following:

- A list of all BMPs being applied to achieve each applicable WLA. For each structural stormwater BMP, the permittee shall provide a unique identification number and geographic coordinate. If the structural stormwater BMP is also included as a part of the pond inventory, the same ID number shall be used.

- A list of all BMPs the submitted at the time of application and the stage of implementation for each BMP.

- An updated estimate of the cumulative reductions in loading achieved for each pollutant of concern associated with each applicable WLA.

- An updated narrative describing any adaptive management strategies used (including project dates) for making progress toward achieving each applicable WLA.

MPCA’s Stormwater Program has developed maps to assist MS4s with identifying impaired waters to which the MS4 discharges. The same may eventually be done for approved TMDLs. One concern is the search criteria are restricted to selected water and downstream waters are difficult to identify. For example, a city such as Minnetonka discharges to Minnehaha Creek, which discharges to the Mississippi River, which could have an impact on Lake Pepin, which is impaired for sediment and nutrients (phosphorus).

TMDL stormwater issues

It is important to provide language in a TMDL that can be supported with the permit. The potential issues can be roughly divided into setting and achieving wasteload allocations. Prior to discussing these, it is important to understand certain aspects of TMDLs.

General information about TMDLs

The TMDL equation

A total maximum daily load (TMDL) is the amount of pollutant loading that can occur and have a water body meet water quality standards. A TMDL may be written as an equation which allocates pollutant loading to four separate categories,

TMDL = WLA + LA + MOS + RC

where WLA is wasteload allocation, LA is load allocation, MOS is margin of safety, and RC is reserve capacity. WLA includes pollutant loading from sources covered by a NPDES permit (often called point sources), LA includes sources not covered by a NPDES permit (often called nonpoint sources), MOS accounts for uncertainty in the estimates of WLA and LA, and RC allows for future growth.

Contents of a TMDL

In addition to pollutant loads, a TMDL must include additional information. Items of greatest interest for permitted stormwater are methods for calculating WLA, reasonable assurances, monitoring, and implementation (which includes timelines). Generally, models are used to calculate pollutant loads. Reasonable assurance language in the TMDL includes guarantees that the pollutant loads are achievable. Language on monitoring provides a general overview of how the TMDL will be tracked. Detailed language on monitoring is often deferred to the TMDL Implementation Plan. Implementation language provides a general overview of how the TMDL loads will be achieved and what the timelines are for meeting the TMDL requirements. The Implementation Plan contains more specific information on implementation. Requirements of a TMDL are enforceable, while the Implementation Plan is not.

Types of TMDLs

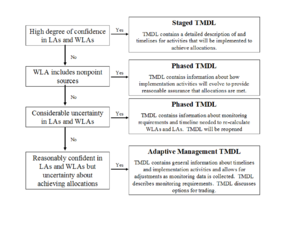

TMDLs may be grouped into one of three categories based on an August 2, 2006 EPA memo ([6]). These categories are somewhat arbitrary but identifying the appropriate type of TMDL early in the process should help develop the TMDL language. In particular, identifying the TMDL category should help identify long term data needs and help frame the Implementation Plan.

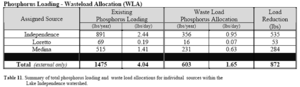

The first type is a Phased TMDL. Phased TMDLs may be preferable when there is significant uncertainty about how the WLA will be met. This uncertainty results from one of two conditions. First, when there is a significant nonpoint component included in the WLA, there may be concerns with reasonably assuring how the WLA will be met. In developing a TMDL, it may be desirable to include nonpoint sources within the WLA if they occur within a municipalities boundaries and if there are reasonable assurances that the municipality can develop the legal tools to achieve the WLA. This is one mechanism to account for future growth (see Section 4b.viii.). EPA recommends that some additional provision in the TMDL, such as a schedule and description of the implementation mechanisms for nonpoint source control measures, be included to provide reasonable assurance that the nonpoint source measures will achieve the expected load reductions. For example, in the Potash Creek TMDL in Vermont, the WLA included several nonpoint sources of pollutant. These nonpoint sources were associated with impervious surfaces greater than one acre in size but not covered by a NPDES permit. Vermont developed a statewide general permit to cover these sources. Consequently, these nonpoint sources were included in the WLA ([7]). Another example is the Lake Independence TMDL, in which the WLA included nonpoint sources within the city boundaries of Independence, Loretto, and Medina. The TMDL states “In the event that voluntary implementation of manure management plans does not occur on the majority of feedlot, Medina and Independence will revise existing Conditional Use Permits or Zoning Ordinances to require compliance.” In the case of a Phased TMDL where the WLA includes nonpoint sources, the TMDL should contain language about the tools that might be available to achieve the WLA.

A second type of Phased TMDL involves a situation where available data only allow for "estimates" of necessary load reductions or for "non-traditional problems" where predictive tools may not be adequate to characterize the problem with a sufficient level of certainty. For this type of TMDL, there is an assumption that the TMDL will need to be revised once adequate data are available to estimate WLAs. The TMDL therefore contains language describing how the data will be collected, rather than focusing on implementing activities to achieve a WLA.

Phased TMDLs must include all elements of a regular TMDL, including load allocations, wasteload allocations and a margin of safety. However, phased TMDLs are assumed to require revision at each phase of the TMDL. Each phase must be established to attain and maintain the applicable water quality standard. In addition, EPA recommends that a phased TMDL document or its implementation plan include a monitoring plan and a scheduled timeframe for revision of the TMDL. Since phased TMDLs will in all likelihood need to be revised and therefore require more overall effort, States should carefully consider the necessity of such TMDLs, for example to meet consent decree deadlines or other mandatory schedules. Upon revision of the loading capacity, wasteload, or load allocations, the TMDL would require re-approval by EPA. Although no examples of Phased TMDLs were found in the literature, the State of Montana has had lengthy discussions on the subject of Phased TMDLs ([8])(This is a dead link).

A second type of TMDL is based on adaptive management and trading provisions ([9]). Adaptive implementation is an iterative implementation process that makes progress toward achieving water quality goals while using any new data and information to reduce uncertainty and adjust implementation activities. Adaptive implementation includes immediate actions, an array of possible long-term actions, effectiveness monitoring, and experimentation for model refinement. An important component of the adaptive management approach is monitoring, which is required to adjust implementation activities. Using adaptive implementation, new information from monitoring is used to appropriately target the next suite of implementation activities. The TMDL should contain language about monitoring requirements needed to implement an adaptive management approach. If monitoring supports significant modification to the TMDL, the TMDL may need to be reopened. This requires EPA approval.

The third type of TMDL, called a staged TMDL, anticipates implementation in several distinct stages. It differs from the adaptive implementation scenario because it is anticipated that the load and wasteload allocations will not require any significant adjustments. Instead, implementation actions will be staged over a period of time. For example, EPA has approved mercury TMDLs where the wasteload allocation to point sources (which would be implemented within five years through the NPDES process) was predicated on long-term reductions in atmospheric mercury deposition.

It is not necessary to fit each TMDL into one of these three categories. It is important to understand the distinctions between these types of TMDLs. That understanding will help guide TMDL language, particularly on the issues of monitoring, information gathering, and implementation. The figure below provides a schematic for selecting a TMDL approach.

Setting wasteload allocations (WLAs)

A November 22, 2002 memo drafted by Robert Wayland and James Hanlon of the US EPA provides some clarification on the issue of setting WLAs for stormwater. Some key points of this memo are summarized below:

- NPDES-regulated stormwater discharges must be addressed by the WLA component of a TMDL;

- NPDES-regulated stormwater discharges may not be addressed by the Load Allocation (LA) component of a TMDL;

- Stormwater discharges not currently covered by a NPDES permit may be addressed by the LA component of a TMDL;

This language makes it clear that construction, industrial, and municipal (MS4) activities covered by a NPDES permit must be addressed by the WLA.

In cases where a TMDL lumps more than one category of regulated stormwater into a single WLA, assumptions must be made to determine what part of the WLA is assigned to each category of stormwater. For example, the Lower Minnesota River Dissolved Oxygen TMDL states “Permitted Stormwater Sites: Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems (MS4), Construction Stormwater Sites, Industrial Stormwater Sites: 1,863 pounds of phosphorus over the two critical low flow months studied or 30.5 pounds of phosphorus per day.” In this case, all permitted stormwater was given a lumped WLA. To address these situations, the following guidance is provided.

Construction stormwater

In most states, construction stormwater general permits contain language that the permit must be consistent with the requirements and assumptions of the TMDL. This places a burden on the TMDL to clarify WLAs for construction stormwater.

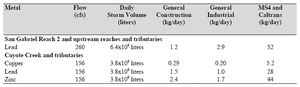

There are examples of TMDLs where construction stormwater is given a separate WLA (see Appendix B for examples of specific TMDL language). In the Caney Fork River Watershed, Tennessee, construction stormwater was given the same percent pollutant reduction as MS4s ([10]). The reductions are to be implemented as BMPs that are described in the state general permit ([11]). However, the permit does not provide specific BMPs, but instead requires the permittee to address the TMDL in their permit. In Idaho, the permitting authority requires incorporation of a gross wasteload allocation for anticipated construction storm water activities into the stream's water quality improvement plan. This WLA is a categorical value which accounts for allowable construction activity in the TMDL for any given point in time. For the San Gabriel Metals TMDL, construction stormwater is given a WLA based on the percent of land area in construction at any one time. Permittees are given a WLA on a per unit area basis ([12]).

MPCA favors a permit-driven process rather than have TMDLs set water quality goals for construction stormwater. Many states assume that meeting the conditions of the construction permit satisfies the TMDL requirement. There are several reasons for employing a permit-driven process.

- Monitoring data from construction sites is lacking. This makes it difficult to accurately calculate a WLA.

- The nature of construction activity is transient. Since the WLA is a static number, loads from construction activity in any given year may be less than or greater than the WLA.

- Reviewing individual permits to determine if they are compliant with the conditions of a TMDL can be burdensome. In some cases, the burden of meeting the TMDL will be passed on to local authorities, who will have to develop specific BMPs for construction activities within their jurisdiction and then ensure compliance. This can be particularly burdensome each time a new TMDL is completed and it places additional requirements on construction stormwater.

- Construction activity constitutes a very small percentage of loading in most watersheds, probably less than 1 percent of the total load. For example, the Rock River and Groundhouse River TMDL studies indicate that land under permitted construction activity constitutes 0.14 and 0.16 percent of the total land area in the watersheds.

- Research indicates that sediment loads from construction sites are small when BMPs are properly installed and maintained (Owens, D.W., P. Jopke, D.W. Hall, J. Balousek and A. Roa 1999. Soil Erosion from Small Construction Sites. Draft USGS Fact Sheet. USGS and Dane County Land Conservation Department, WI).

- MPCA’s proposed construction stormwater general permit contains additional BMPs when construction activity occurs within one mile of an impaired water.

MPCA therefore assumes that permittees in compliance with the requirements of a construction stormwater permit are achieving their WLA.

However, the TMDL process requires a balanced equation. The WLA therefore must be a number. Individual sectors that contribute to loading must be included in the TMDL equation, regardless of whether that loading is considered to be negligible. The following conditions must be considered when setting a WLA for construction stormwater activity.

- Failure to include construction stormwater in a WLA can be interpreted to mean zero allowable discharge from construction activity;

- Use of an approximate load, such as “de minimus” or “insignificant” can be interpreted as zero.

Discharges of zero are not appropriate for construction stormwater. It is therefore not acceptable to include these general terms when setting a WLA for construction stormwater.

Because construction activity must receive a numerical WLA the following approach is recommended.

- A categorical WLA can be established for stormwater. This WLA would include municipal, construction, and industrial stormwater. The TMDL would therefore assign a WLA to stormwater without differentiating how that WLA is distributed among the permitted entities. This should only be done when all construction and industrial stormwater discharges are to a regulated MS4.

- Individual WLAs can be assigned for the different stormwater sectors, including construction stormwater. The WLA would lump all construction stormwater into an individual construction stormwater WLA. If monitoring data is available, it can be used to set the construction WLA. Monitoring data is generally not available. Consequently, the recommended approach for construction stormwater is to estimate the area of the watershed under permitted construction activity. A five year median could be used for this calculation to account for variation in levels of construction activity. The WLA would then be estimated as the median percent of land area under construction times the sum of the overall LA and WLA (i.e. the Margin of Safety and Reserve Capacity are not included in the calculation). MPCA’s Stormwater Program can provide the information needed to make this calculation.

- In some cases a Reserve Capacity may be established to account for increases in and uncertainty in loading from construction activity. This Reserve Capacity can be sector specific. Thus, construction activity may receive a separate Reserve Capacity. This may be a preferred approach when construction activity will greatly increase in the future. For most situations, this is not a favored approach because Reserve Capacity removes load from other sources, there are challenges to distributing Reserve Capacity equitably, it is difficult to estimate what the Reserve Capacity should be, and Reserve Capacity ties up load once construction activity decreases. In addition, MPCA’s TMDL program recommends against using reserve capacity.

These options should be utilized in any TMDL where the pollutant or stressor of impairment is phosphorus (nutrient eutrophication biological indicators), turbidity, dissolved oxygen, or biotic impairment (fish bioassessment, aquatic plant bioassessment and aquatic macroinvertebrate bioassessment).

It is important for TMDL developers to remember that the MPCA favors a permit-driven process for construction stormwater. Appendix A of the 2013 Construction General Permit includes additional BMPs for construction activities that occur within one mile of an impaired water. In addition to or in place of these BMPs, a TMDL can prescribe BMPs for construction stormwater. Permittees must comply with these BMPs. In the case where a TMDL provides a specific WLA for construction stormwater, it will be important for TMDL developers to receive input from Construction Stormwater personnel.

Because MPCA believes that following the conditions of the Construction Stormwater general Permit meets the conditions of a TMDL, TMDLs should contain the following language in the load calculation section of the TMDL.

- For categorical stormwater WLAs:The stormwater wla includes loads from construction stormwater. Loads from construction stormwater are considered to be a small percent of the total WLA and are difficult to quantify. The WLA for stormwater discharges from sites where there are construction activities reflects the number of construction sites one or more acres expected to be active in the watershed at any one time, and the best management practices (BMPs) and other stormwater control measures that should be implemented at the sites to limit the discharge of pollutants of concern. The BMPs and other stormwater control measures that should be implemented at construction sites are defined in the State's NPDES/SDS General Stormwater Permit for Construction Activity (MNR100001). If a construction site owner/operator obtains coverage under the NPDES/State Disposal System (SDS) [Permit] General Stormwater Permit and properly selects, installs and maintains all BMPs required under the permit, including those related to impaired waters discharges and any applicable additional requirements found in Appendix A of the Construction General Permit, the stormwater discharges would be expected to be consistent with the WLA in this TMDL. It should be noted that all local construction stormwater requirements must also be met.

- For an individual WLA for construction stormwater: The WLA for stormwater discharges from sites where there are construction activities reflects the number of construction sites one or more acres expected to be active in the watershed at any one time, and the best management practices (BMPs) and other stormwater control measures that should be implemented at the sites to limit the discharge of pollutants of concern. The BMPs and other stormwater control measures that should be implemented at construction sites are defined in the State's NPDES/SDS General Stormwater Permit for Construction Activity (MNR100001). If a construction site owner/operator obtains coverage under the NPDES/State Disposal System (SDS) [Permit] General Stormwater Permit and properly selects, installs and maintains all BMPs required under the permit, including those related to impaired waters discharges and any applicable additional requirements found in Appendix A of the Construction General Permit, the stormwater discharges would be expected to be consistent with the WLA in this TMDL. It should be noted that all local construction stormwater requirements must also be met.

Municipal stormwater

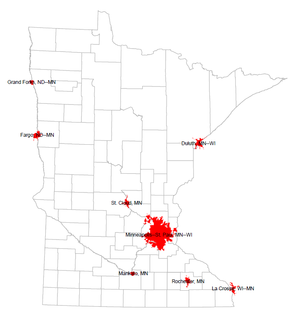

Publicly owned conveyance systems partly or fully within one of Minnesota’s eight urban areas (Metro, Duluth, Rochester, St. Cloud, Winona-LaCrosse, East Grand Forks-Grand Forks, Moorhead-Fargo, Mankato) are considered Mandatory MS4s. This includes conveyance systems owned by cities, townships, counties, watershed districts, MN DOT, and other public entities such as the University of Minnesota, Minnesota state colleges and technical institutes, and state-owned correctional facilities. The list of mandatory MS4s in Minnesota can be found at http://www.pca.state.mn.us/publications/wq-strm4-74.pdf. Minneapolis and St. Paul are Phase I cities and require individual permits. The figure below illustrates the location of Minnesota’s urban areas, as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau.

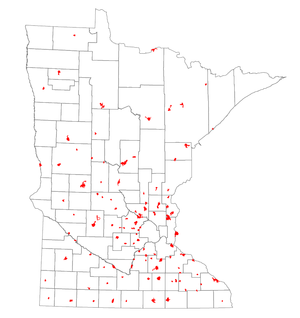

There are also several designated MS4s in Minnesota. These include cities with populations greater than 10,000, and cities with populations of 5,000 to 10,000 that have the potential to discharge to an impaired or Outstanding Resource Value water. The figure below illustrates the location of designated MS4s in Minnesota.

Permit coverage exists only for those parts of the stormwater conveyance system that are owned and operated by the permittee. For example:

- MN DOT requires permit coverage for only that part of the conveyance system associated with a state highway that occurs within one of the seven urban areas. Permit coverage is not required for portions of the same highway that exist outside an urban area.

- Counties and watershed districts require permit coverage only for those conveyances it owns (e.g. county ditches, roads, etc.) within an urban area. Permit coverage is not required for portions of the same conveyance structure that exist outside an urban area.

- Portions of state owned conveyances, such as state colleges, universities, and correctional facilities, require permit coverage if they exist within an urban area. Portions outside an urban area do not require coverage (e.g. University of Minnesota at Morris)

- Privately-owned conveyances, including conveyances owned by industrial facilities, commercial facilities, and private residences, are not covered under the MS4 general permit even if they discharge to a permitted conveyance. Note that most industrial facilities and some commercial facilities require individual permits or are covered under one of the industrial general permits.

The above information raises three concerns. First, it can be difficult to identify all permitted MS4s for a particular TMDL. Second, calculating WLAs can be difficult for some of the non-traditional MS4s, such as MN DOT, counties, watershed districts, and state-owned facilities. Finally, the stormwater permit only requires the permittee to address its own operations and new construction (post construction requirements). Consequently, the permit does not cover runoff from private property that does not have post construction requirements. However, a regulated MS4 community is responsible for all discharges from conveyances they own or operate, regardless of how those discharges reach their system.

Despite these difficulties, TMDL language must address each of these issues. A TMDL must list all permitted MS4s within the TMDL study area. Preferably, the TMDL would include the MS4 Permit Number and individual IDs for each MS4 receiving a WLA. For counties, highways, or watershed districts that require permit coverage only within an urban area, the TMDL should identify those areas that require permit coverage.

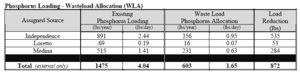

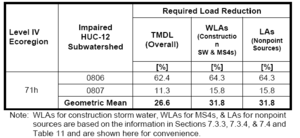

Each of these MS4s must be given a WLA. The WLA may be categorical or individual (individual allocations should be distributed if at all possible). An example of a categorical WLA is the 30 percent phosphorus reduction for ten MS4s named in the Lower Minnesota River Low Flow Dissolved Oxygen TMDL ([13]). An example of individual WLAs is the Lake Independence nutrient TMDL, where individual phosphorus WLAs were given to each of the three municipalities in the study area ([14]).

Assigning a WLA to a MS4 provides reasonable assurances that the WLA will be met, provided all discharges covered by the WLA enter the MS4’s conveyance. In a case where much of the MS4’s discharge originates from private property, the MS4 will have to implement activities to control or treat these discharges. For example, a permitted MS4 may develop ordinances to cover discharges from private properties.

Industrial stormwater

MPCA’s multisector industrial general permit was issued in 2010. The permit includes language that shortens the time permittees have to install BMPs when their stormwater discharges cause or contribute to a water quality violation (e.g. impairment).

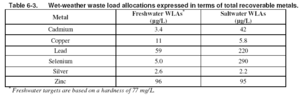

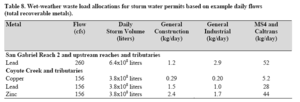

There are some examples of TMDLs that have individual WLAs for industrial stormwater. The Ballona Creek TMDL states that each storm water permittee enrolled under the general construction or industrial storm water permits will receive an individual waste load allocation on a per acre basis, based on the acreage of their facility ([15])(This is a dead link). “The general industrial storm water permits shall achieve final wet-weather waste load allocations no later than 10 years from the effective date of the TMDL, which shall be expressed as NPDES water quality-based effluent limitations. Effluent limitations may be expressed as permit conditions, such as the installation, maintenance, and monitoring of Regional Board approved BMPs if adequate justification and documentation demonstrate that BMPs are expected to result in attainment of waste load allocations.” “BMP effectiveness monitoring will be implemented to determine progress in achieving interim wet-weather waste load allocations.” The storm water waste load allocations are apportioned between the MS4 permittees, Caltrans, the general construction and the general industrial storm water permits based on an area weighting approach.

Permits for storm water discharges associated with industrial activity are to require compliance with all applicable provisions of Sections 301 and 402 of the CWA, i.e., all technology-based and water quality-based requirements. EPA also recognizes that the available data and information usually are not detailed enough to determine waste load allocations for NPDES-regulated storm water discharges on an outfall-specific basis. In this situation, EPA recommends expressing the wasteload allocation in the TMDL as either a single number for all NPDES-regulated storm water discharges, or when information allows, as different WLAs for different identifiable categories, e.g., industrial stormwater as distinguished from storm water discharges from construction sites or municipalities. These categories should be defined as narrowly as available information allows (e.g., for industrial sources, separate WLAs for different types of industrial storm water sources or dischargers).

Much of the discussion for construction stormwater applies to industrial stormwater. This includes the difficult nature of calculating loads from industrial facilities, the relatively small contribution from industrial stormwater if permit conditions are met, and the variability in types of industrial facilities.

Consequently, the recommended options for construction stormwater apply to industrial stormwater. These are summarized below.

- Estimate a WLA for industrial stormwater. This differs from calculating a WLA because monitoring data is not used to set the WLA. Instead, the WLA is set using other general criteria, such as percent of land area in the watershed that is currently under industrial activity covered by a permit. This is a reasonable approach. The TMDL should contain additional language to indicate industrial stormwater that is in compliance with the permit meets water quality standards and therefore has no load reduction requirement. The following standard language should be included: The WLA for stormwater discharges from sites where there is industrial activity reflects the number of sites in the watershed for which NPDES industrial stormwater permit coverage is required, and the BMPs and other stormwater control measures that should be implemented at the sites to limit the discharge of pollutants of concern. The BMPs and other stormwater control measures that should be implemented at the industrial sites are defined in the State's NPDES/SDS Industrial Stormwater Multi-Sector General Permit (MNR050000) or facility specific Individual Wastewater Permit (MN00XXXXX) or NPDES/SDS General Permit for Construction Sand & Gravel, Rock Quarrying and Hot Mix Asphalt Production facilities (MNG490000). If a facility owner/operator obtains stormwater coverage under the appropriate NPDES/SDS Permit and properly selects, installs and maintains all BMPs required under the permit, the stormwater discharges would be expected to be consistent with the WLA in this TMDL. It should be noted that all local stormwater management requirements must also be met.

The load for industrial stormwater can be lumped with municipal stormwater. This approach is acceptable although it creates difficulty for MPCA when reviewing SWPPPs, since the WLA is not clear. This problem can be addressed by including the following language in the TMDL: The stormwater wla includes loads from industrial stormwater. Loads from industrial stormwater are considered to be less than 1 percent of the total wla and are difficult to quantify. The WLA for stormwater discharges from sites where there is industrial activity reflects the number of sites in the watershed for which NPDES industrial stormwater permit coverage is required, and the BMPs and other stormwater control measures that should be implemented at the sites to limit the discharge of pollutants of concern. The BMPs and other stormwater control measures that should be implemented at the industrial sites are defined in the State's NPDES/SDS Industrial Stormwater Multi-Sector General Permit (MNR050000) or facility specific Individual Wastewater Permit (MN00XXXXX) or NPDES/SDS General Permit for Construction Sand & Gravel, Rock Quarrying and Hot Mix Asphalt Production facilities (MNG490000). If a facility owner/operator obtains stormwater coverage under the appropriate NPDES/SDS Permit and properly selects, installs and maintains all BMPs required under the permit, the stormwater discharges would be expected to be consistent with the WLA in this TMDL. It should be noted that all local stormwater management requirements must also be met.

Individual permits

Minneapolis and St. Paul are Phase 1 communities and require individual permit coverage. The discussion in Section 4biii covers recommended TMDL language for these cities.

Minnesota issues a number of individual stormwater permits, such as those issued to commercial facilities. In general, pollutant loading from these facilities will be small compared to other permitted sources. Additionally, discharge from these facilities often enters a publicly-owned (MS4) conveyance, which may be addressed through the MS4 permit assuming reasonable assurances can be provided. However, in small watersheds and in situations where private permittees discharge directly to an impaired water, a separate WLA is warranted.

Choosing categorical or individual WLAs and the form of the WLA

The Wayland memo states “It may be reasonable to express allocations for NPDES-regulated storm water discharges from multiple point sources as a single categorical wasteload allocation when data and information are insufficient to assign each source or outfall individual WLAs. See 40 C.F.R. § 130.2(i). In cases where wasteload allocations are developed for categories of discharges, these categories should be defined as narrowly as available information allows.”

In certain cases, TMDLs will assign categorical WLAs . A categorical WLA may be desirable under four circumstances. First, a categorical WLA is appropriate if pollutant loading from all permitted stormwater sources is likely to be similar in nature. This would be the case for construction stormwater and for industrial stormwater within the same SIC category. For example, the San Gabriel Metals TMDL assigns a pollutant load per day to all construction activity. A categorical allocation for construction or industrial should take the form of a pollutant load per unit area.

Second, a categorical WLA is appropriate when each permittee can perform the same stormwater management activities to accomplish the requirements of the TMDL. For example, this situation applies to MS4s when Pollution Prevention, Good Housekeeping, and Education BMPs alone are likely to achieve the WLA. These activities will typically be the same for each permittee and a categorical approach is therefore appropriate. This situation also occurs when the TMDL prescribes a set of BMPs for more than one stormwater entity and those BMPs alone will achieve the WLA.

Third, categorical WLAs are also appropriate when data are inadequate for assigning individual WLAs. This will often be the case for very large watersheds where the modeling cannot achieve sufficient detail to allocate individual WLAs. Examples include the lower Minnesota River Dissolved Oxygen TMDL, the Lake Pepin TMDL (in progress), and the Lower Minnesota Turbidity TMDL (in progress).

Finally, categorical WLAs may be appropriate when a single MS4 or other entity will track BMP implementation and associated load reductions. An example would be a watershed district. However, MPCA has developed guidance that suggests the tracking entity should have regulatory authority and a proven history of implementation.

The WLA can be considered categorical in nature if it includes the load for two or more of the following sectors:

- Construction stormwater;

- Industrial stormwater;

- Individually-permitted MS4 stormwater; and

- MS4 stormwater covered under a General Permit.

Categorical WLAs can be problematic for two reasons. First, consider the example shown in the figure below, which is an allocation from the Lower Mississippi River Fecal Coliform TMDL. The MS4 allocations are shown in pink. Four MS4s in this sub-basin were given these categorical WLAs. This treats each MS4 equally, which may be an incorrect assumption if there are pollution hotspots within some MS4s. There is also an issue of dividing the WLA among the four MS4s. The problem of dividing up the WLA can be overcome by stating the WLA on a per unit area basis or as a required reduction, stated as a percentage.

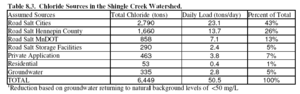

A second concern with categorical allocations is that adjustments in the WLA will be required if the categorical WLA cannot be achieved. For example, the Shingle Creek Chloride TMDL requires a categorical 71% reduction in chloride loading. This applies to all MS4s in the TMDL study area. The BMPs used to achieve this reduction are prevention and good housekeeping BMPs that can be implemented equally by each MS4. If these BMPs do not achieve the desired reduction, it may be necessary to adjust the WLA to target areas where pollutant loading is greatest, which means individual WLAs.

If data support it, individual WLAs for each MS4 are desired. This will most commonly be done for small watersheds with a small number of MS4s and for which pollutant loading is well understood. For example, the Lake Independence Nutrient TMDL provides individual WLAs to the cities of Loretto, Independence, and Medina (figure below).

Individual WLAs can be in the form of a required reduction from current loading, a mass load, or a load per unit area or per unit time basis. In addition to the traditional units of quantity per unit time, MPCA recommends expressing the TMDL as a reduction from a defined baseline. This is consistent with requirements in the MS4 general permit. An example baseline would be a year or a set of BMPs.

In some cases, the WLA can be expressed as a mass that has been translated from a desired reduction. For example, assume the goal is to implement a particular suite of BMPs. We can determine load reductions associated with those BMPs. The total reduction, as a percent, can be multiplied by the estimated current load. This yields a WLA expressed as a mass, even though the WLA will be achieved by implementing a specific set of BMPs. This may be a desirable approach for large watershed TMDLs. These TMDLs can be a concern because required reductions are often very large and modeling methods are not sufficient for calculating current loads for individual MS4s. Consequently, it is preferred to identify a suite of BMPs that would result in load reductions but not drive local stormwater management.

Sections 4b.ii., 4b.iii, 4b.iv, and 4b.v. summarize recommended policy on form of the WLA.

Adjusting WLAs

A TMDL assigns an overall WLA, which may then be divided among different permitted sources. Often, data used to quantify pollutant loading improves with time. Individual WLAs for permitted sources may be modified or adjusted after the TMDL is completed, provided the overall WLA does not change. Similarly, EPA now supports transfer of LA to WLA. In each of these cases, the TMDL should describe the process for transferring load. The overall TMDL cannot change. Individual permittees should be notified of the changes, but the TMDL does not need to be re-noticed.

Accounting for future growth

In TMDLs, future growth can be accommodated in three ways. A Reserve Capacity may be established. This eventually limits growth since at some point reserve capacity is used up. In addition, it is difficult to determine how the Reserve Capacity should be divided among different sources. MPCA does not support the use of Reserve Capacity.

Future growth may also be accommodated with the WLA. 40 CFR 130.2 states “(h) Wasteload allocation (WLA). The portion of a receiving water’s loading capacity that is allocated to one of its existing or future point sources of pollution.” Consequently, future point sources of pollution can be included in the WLA.

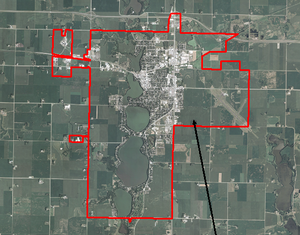

Consider the figure below, which shows the municipal boundaries for the city of Fairmont. Much of the municipality consists of agricultural land, which typically is included in the LA. However, if Fairmont was a growing city and anticipated that the entire municipality would eventually be urbanized, the entire municipality could be included in the WLA because it will eventually be covered by a NPDES permit. This is a desirable situation for the city because they are allowed future growth and because they may, depending on the pollutant, achieve load reductions by converting agricultural land to urban land. The Lower Minnesota River Dissolved Oxygen TMDL assumed agricultural land in Fairmont was part of the LA. Consequently, growth of Fairmont must either be accommodated through Reserve Capacity, by decreasing loads within the existing urban area, or through trading.

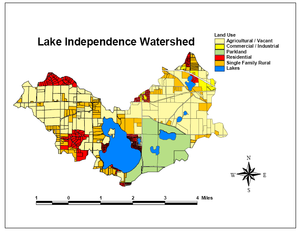

The Lake Independence TMDL is an example in which the permitted municipalities of Medina, Independence, and Loretto assumed WLAs for their entire municipality, even though considerable portions of the area are not covered by the MS4 permit (figure below). Incorporating the entire area into the WLA allows for future growth.

Point sources included in the WLA are covered by a permit, which provides a reasonable assurance that the WLA will be achieved. If the WLA includes nonpoint pollution sources, the TMDL must contain reasonable assurances that the WLA can be achieved. For example, in the Potash Brook TMDL, the WLA includes pollution sources not covered by a NPDES permit. The following assurance is provided for these sources: “VTDEC implements both a federally-authorized NPDES permit program for stormwater discharges from construction activities, industrial activities and municipal discharges under the MS4 program and a state-authorized permitting program for stormwater discharges from impervious surfaces equal to or greater than one acre.” ([16]). In the Lake Independence TMDL, feedlot manure is an important nonpoint source included in the WLA. The TMDL contains the following language: “In the event that voluntary implementation of manure management plans does not occur on the majority of feedlot, Medina and Independence will revise existing Conditional Use Permits or Zoning Ordinances to require compliance. In cooperation with the Pioneer-Sarah Creek Watershed Management Commission, Three Rivers Park District, and Hennepin County Environmental Services (HCES), Medina and Independence will develop a manure hauling and disposal service to assist landowners with manure management.

Projected growth can be accommodated in the WLA. In this situation, a certain percentage of the LA is put into the WLA to account for the projected growth. This approach requires a specific time frame (e.g. 2030, 20 years, etc.) and reasonable demographic information. Equity issues may arise if the allocation for growth is categorical, rather than providing each community with a specific allowable WLA. Another concern is the form of land use change. For example, conversion of agricultural land to urban land may decrease pollutant loading, while the opposite is true for conversion of forest to urban. A final factor is the post-construction requirement for urban land. More stringent requirements, including utilization of Low Impact Development, can achieve substantial pollutant reductions.

One concern with putting nonpoint sources into the WLA is potential encouragement of land acquisition. Municipalities may see growth as a way to meet TMDL requirements. This may be partly offset by restricting the area of growth to the current municipal boundaries and considering growth over some limited time frame, such as the year 2030.

As with any pollutant loading, reasonable assurances must be provided that the WLA can be achieved. This means municipalities must be involved in setting the WLA so that reasonable targets and voluntary or regulatory tools can be identified in the TMDL.

A third and final approach is to define the WLA by current land use but allow LA to WLA transfers. This approach has only recently gained support from EPA Region 5. This approach is easy to incorporate into a TMDL and is the most accurate way of expressing loads. However, it places a burden on the permitting authority to track growth and ensure that transfers are occurring. The TMDL should describe the process of LA to WLA transfer.

WLAs for permitted MS4s and LAs for non-permitted MS4s

Generally, pollutant loading from permitted and non-permitted MS4s is similar in nature. Consequently, methods for calculating the WLA and LA from MS4s should be the same. TMDL requirements should thus be the same for permitted and non-permitted MS4s.

Recommendations

Based on the above discussion, the following recommendations are made.

- Because data are generally not available for developing individual WLAs for construction stormwater, it is MPCA’s preference to utilize the construction general permit to manage compliance with a TMDL. When adequate data are available, construction stormwater should be given a separate WLA (wasteload allocation). If a separate wasteload allocation is given, all construction stormwater should receive the same WLA (categorical WLA). The preferred form of the load is pollutant (e.g. mass, organisms, etc.) per unit area. If a TMDL provides a separate WLA for construction stormwater, the TMDL should contain specific language about actions that will be required. If a separate WLA is not given to construction stormwater, or if the TMDL does not prescribe additional BMPs to meet the WLA, then MPCA assumes construction activity that follows the conditions of the state general permit and local requirements meets requirements of the TMDL. TMDLs that do not prescribe additional BMPs for construction stormwater should contain the language presented in Section 4.b.ii of this guidance document.

- A TMDL must name each permitted MS4 within the TMDL study area. The TMDL should list the permit number and individual ID for each MS4. The TMDL must provide a WLA for each permitted MS4. This WLA will be categorical or individual. If data are adequate, individual WLAs should be given to each permitted MS4. The TMDL should be expressed as a reduction from a defined baseline in addition to traditional ways of expressing the TMDL.

- Future discharges, including growth, should be accommodated in the TMDL, either by incorporating them into the WLA or by describing load transfers in the TMDL report. MPCA has developed guidance describing how to address future discharges (See Guidance on what discharges should be included in the Wasteload Allocation for MS4 stormwater at [17]).

- Because data are generally not available for developing individual WLAs for industrial stormwater, it is MPCA’s preference to utilize the industrial multisector general permit to manage compliance with a TMDL. Data resulting from benchmark monitoring of industrial stormwater discharges cannot be used to establish a separate WLA for industrial stormwater. When effluent limits are established for an industrial sector, that sector may be given a separate WLA. If a separate wasteload allocation is given for an industrial stormwater sector, all facilities within the sector should be given a single combined WLA (categorical WLA). The preferred form of the load is pollutant (e.g. mass, organisms, etc.) per unit area. If a TMDL provides a separate WLA for industrial stormwater, the TMDL should contain specific language about actions that will be required. If a separate WLA is not given to industrial stormwater, or if the TMDL does not prescribe additional BMPs to meet the WLA, then MPCA assumes industrial activity that follows the conditions of the state multisector general permit meets requirements of the TMDL. TMDLs should contain the language presented in Section 4.b.iv of this guidance document.

- When data allows, discharges covered under individual permits may be given a separate WLA. If a separate wasteload allocation is given, it should be individual for each permittee. The preferred form of the WLA is quantity of pollutant (e.g. mass, organisms, etc.). If a TMDL provides a separate WLA for these discharges, the TMDL and TMDL Implementation Plan should contain specific language about actions that will be required and identify the organization(s) responsible for administering those actions. If a separate WLA is not given to these discharges, then MPCA assumes activity that follows the conditions of the permit meets requirements of the TMDL. If a separate WLA is not given to these discharges, the TMDL should contain the following language: “Storm water activities from individually permitted, non-MS4 NPDES/SDS stormwater discharges will be considered in compliance with provisions of the TMDL if they follow conditions of the individual permit and implement the appropriate Best Management Practices.”

- If pollutant load allocations or modeling assumptions differ for permitted and non-permitted MS4s, the TMDL must clearly state the basis for the difference.

Implementation

TMDLs include sections on Reasonable Assurances, Implementation, and Monitoring. In Minnesota, a TMDL Implementation Plan is completed within one year of EPA approval of the TMDL. The TMDL and Implementation Plan therefore contain information about how to achieve the WLAs.

Reasonable assurances

A TMDL must contain reasonable assurances that the WLA can be achieved. For point sources, NPDES permits provide reasonable assurances. Permitting authorities should be identified in the TMDL. For nonpoint sources, reasonable assurances may take several forms. These include adoption of ordinances, local regulatory controls (e.g. watershed district regulations), and projected growth. These have been discussed in greater detail above.

Achieving the WLA

The Wayland memo states “WQBELs [Water Quality Based Effluent Limits] for NPDES-regulated storm water discharges that implement WLAs in TMDLs may be expressed in the form of best management practices (BMPs) under specified circumstances. See 33 U.S.C. §1342(p)(B)(iii); 40 C.F.R. §122.44 (k)(2)&(3). If BMPs alone adequately implement the WLAs, then additional controls are not necessary. EPA expects that most WQBELs for NPDES-regulated municipal and small construction storm water discharges will be in the form of BMPs, and that numeric limits will be used only in rare instances.”

This memo makes it clear that BMPs can be used to achieve TMDL requirements. The approach for achieving a TMDL WLA varies with the scale of the TMDL study. For small watersheds where stormwater from permitted MS4s accounts for the majority of the WLA and pollutant loadings can be reasonably quantified, the WLA will be achieved through a combination of BMP implementation and monitoring. MS4s will implement BMPs appropriate for the pollutant of concern. Each BMP will be associated with a load reduction based on the pollutant removal efficiency of the BMP and the area affected by the BMP. Pollutant removal efficiency will be a function of maintenance of the BMP. Water quality monitoring will be coupled with BMP implementation. Monitoring occurs in the receiving water body. The TMDL is met when the water quality standard is met and each MS4 has carried out a minimum set of BMPs that are described in the TMDL and TMDL Implementation Plan.

Monitoring is impractical for large watersheds. For large watersheds, the TMDL is met by implementing BMPs and receiving a pollutant reduction credit.

There are four ways of achieving the WLA. These include use of BMPs, land use changes, benchmarking, and trading.

BMPs can be non-structural or structural. Non-structural BMPs include Good Housekeeping practices, pollution prevention, and education. Structural BMPs include constructed wetlands, biofiltration systems, infiltration devices, ponds, and so on. For ease of crediting, it is best if the TMDL WLA is calculated assuming no BMPs in place. With this scenario, any activity that reduces pollutant loading and is not associated with one of the six minimum control measures is credited toward achieving the TMDL requirement, regardless of when the BMP or activity was implemented. MPCA is exploring ways to determine load reductions associated with different BMPs. If a TMDL prescribes specific BMPs or pollutant reduction activities beyond the six minimum control measures (The MS4 stormwater general permit requires the permittee to submit a SWPPP that addresses six minimum control measures. In a non-TMDL situation, the SWPPP includes a minimum of 30 BMP data sheets that encompass the six minimum measures. These non-TMDL SWPPPs define a level of stormwater management considered suitable for maintaining current water quality in receiving water bodies. These cannot be used to achieve TMDL-required load reductions unless the permittee goes above and beyond the standard requirement of an MCM.), the TMDL should quantify the expected load reduction associated with each BMP. If a TMDL assumes BMPs in calculating the WLA, individual WLAs should be provided to permittees that have implemented the BMPs used in the model.

A benchmark is a standard against which something is measured. For example, a water quality standard is a benchmark against which effluent concentrations in stormwater runoff may be compared. Assuming the ultimate objective of stormwater management is to achieve water quality standards, a variety of water quality benchmarks can be developed. Examples include changes in land use that typically result in a pollutant load increase or decrease. For example, conversion of row crop agricultural land to residential land that utilizes Low Impact Development (LID) BMPs will generally result in a substantial decrease in pollutant loading. The TMDL should contain language indicating that pollutant loads may be increased or decreased with land use changes, and that these changes will either increase or decrease the required reduction in loading. A credit system is currently being developed for these types of land use changes.

Trading can be done between different WLAs. For WLA to WLA trading, one MS4 buys pollutant loading from either another MS4 or other permitted source, such as a wastewater treatment plant (WWTP). This is desired when the cost of buying the pollutant is less than the cost of implementing BMPs to achieve the WLA. Trading presents a number of challenges. First, it must be determined how to generate tradable pollutant. It cannot be generated until the conditions of a TMDL have been met or until it is determined that a MS4 cannot reasonably achieve further load reductions. Second, there may be future TMDLs that are more restrictive, which would negate tradable pollutant generated with a less restrictive TMDL. Third, some MS4s may reach the TMDL target by implementing their requirements under the permit, while some MS4s will need to implement BMPs. This makes it easier for some MS4s to generate tradable pollutant. Finally, a system of accounting will need to be developed.

Although MPCA favors all forms of trading, federal trading policy is unclear. In particular, it is unclear if WLA can be traded for LA, or vice versa. MPCA has formed a trading work group. At a minimum, trading should not be allowed during the first permit cycle until this work group has developed appropriate policy.

Monitoring

Monitoring may occur at three levels. First is water quality monitoring of stormsheds. Second is monitoring the effectiveness of specific BMPs. These two types of monitoring will be typically conducted through the MPCA and its partner organizations. The third type of monitoring involves maintenance of BMPs. MS4s will be required to monitor BMPs to ensure they are well maintained and functioning. The process for conducting this monitoring will be documented through the SWPPP.

Implementation language in the TMDL

When sufficient data exist, a TMDL may identify specific BMPs. An example is the good housekeeping BMPs identified in the Shingle Creek TMDL. The Shingle Creek chloride TMDL states “Member cities of the SCWMC, Mn/DOT, and Hennepin County have all agreed to identify and implement BMPs focused on reducing chloride use in the Shingle Creek watershed … To this end, the stakeholders in the watershed have agreed to incorporate the following practices:

- Annually calibrate spreaders.

- Use the Road Weather Information Service (RWIS) and other sensors such as truck mounted or hand held sensors to improve application decisions such as the amount and timing of application.

- Evaluate new technologies such as prewetting and anti-icing as equipment needs to be replaced. These technologies will be adopted where feasible and practical.

- Investigate and adopt new products (such as Clear Lane, a commercially available pretreated salt) where feasible and cost effective.

In most cases, more general language will be desired, since the relationship between BMPs and load reductions are not well understood. For example, the Lower Minnesota River Dissolved Oxygen TMDL states “SWPPPs need to be consistent with TMDL allocation requirements and implementation plans.”

Permitted MS4s have expressed a desire for the TMDL to provide a general plan for implementation, but for the Implementation Plan to provide specific information about how to achieve the TMDL requirement. This requires MS4s to participate in the TMDL process.

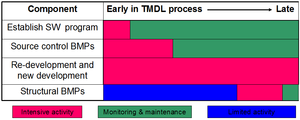

Implementation and timelines

We currently have an incomplete understanding of the relationship between BMP implementation and pollutant reduction. In addition, a certain group of BMPs may be appropriate for one pollutant but inappropriate for another pollutant. Consequently, a TMDL should be consistent with the recommended timeline shown in the figure below. The figure indicates that establishing a stormwater program is the first step in the TMDL implementation process. Although this does not achieve pollutant reductions that are likely to be credited toward a TMDL, it is important to have a stormwater program in place to implement BMPs in the future. In the early part of a TMDL, prevention, education, good housekeeping, and methods to address new development and re-development are encouraged. Structural BMPs should not be encouraged until a MS4 has a good understanding of the pollutant loading reduction associated with the structural BMP.

The TMDL can appropriately identify the SWPPP as the place where a permitted MS4 will discuss BMPs to be implemented in response to TMDL requirements. The advantages of relying on the SWPPP are that it has the force of the permit and the SWPPP contains measurable goals and timelines. At this time the stormwater program is determining how to better link the SWPPP with stormwater management and with TMDLs.

Other issues

A variety of issues have been identified but not fully discussed. These are briefly summarized below.

Stakeholder process

Identifying all permitted MS4s in a TMDL provides an early mechanism to involve stakeholders in the TMDL process. Engaged stakeholders help improve the clarity of TMDL language, particularly implementation.

There has been a wide range of stakeholder involvement in TMDL development. Many stakeholders, particularly those outside the Twin Cities Metro area, are unfamiliar with impaired waters and the TMDL process. Many are also not completely informed about stormwater permits and SWPPPs, particularly for municipal stormwater. The Stormwater Program is developing a series of training modules to help inform stakeholders. The modules are similar to those developed by the TMDL program and are intended to be delivered by TMDL staff. The modules include information on the stormwater permit and SWPPPs, the relationship of the SWPPP and the TMDL, establishing a stormwater program, and pollutant specific guidance.

For TMDLs in which MS4s are one of multiple pollutant sources, MS4s should organize a separate advisory committee. One or more representatives of the committee should serve on the TMDL advisory committee. For TMDLs in which MS4s are the only pollutant source, all MS4s should be represented. The Shingle Creek TMDL provides an example of several MS4s that worked together to develop a TMDL and an implementation strategy.

In an EPA-designated urban area, there may be several non-traditional MS4s. Examples include watershed organizations, counties, the Minnesota Department of Transportation, and facilities such as the University of Minnesota. These MS4s should have representation. It is important to identify overlapping responsibilities when multiple MS4s are involved. For example, a watershed management organization may be the best organization to facilitate development of a TMDL. Also, counties and watershed organizations may have requirements for individual cities, such as a water plan. These local requirements should be aligned, if possible, with TMDL requirements.

Several resources are available to organize MS4s. Examples include the League of Minnesota Cities, Watershed Management Organizations, and the Minnesota Cities Stormwater Coalition. In addition, by the end of 2007, all permitted MS4s will have submitted SWPPPs to the MPCA. This provides a mechanism for identifying and contacting the lead person(s) for the MS4.

Maximum extent practicable

Minnesota’s MS4 general permit “states Your Storm Water Pollution Prevention Program must be designed and managed to reduce the discharge of pollutants from your storm sewer system to the Maximum Extent Practicable (MEP). You must manage your municipal storm sewer system in compliance with the Clean Water Act and with the terms and conditions of this permit. You must manage, operate, and maintain the storm sewer system and areas you control that discharge to the storm sewer system in a manner to reduce the discharge of pollutants to the MEP. The Storm Water Pollution Prevention Program will consist of a combination of Best Management Practices, including education, maintenance, control techniques, system design and engineering methods, and such other provisions as You determined to be appropriate, as long as the BMPs meet the requirements of this permit”.

The meaning of MEP has been widely debated. The US EPA purposely did not define MEP to allow MS4s flexibility as they developed their SWPPPs. Additionally, having MEP undefined allows states to modify their permit and address stormwater management through multiple permit cycles.

MEP could loosely be defined as whatever is included in an approved SWPPP. This would be, at a minimum, completed BMP worksheets for the six minimum control measures. However, an approved permit containing only the necessary BMP worksheets is considered appropriate to maintain the current water quality of receiving waters. Thus, when receiving water is impaired, additional BMPs are needed to return the impaired water to its intended use. MPCA acknowledges that MS4 permit requirements, and thus MEP, will have to evolve over time, particularly in response to impaired waters.

MPCA expects to modify the permit as needed to eventually achieve water quality standards and non-degradation requirements. Along the way, MPCA will develop guidance and tools for MS4s to use in refining their SWPPPs.

Non-degredation and TMDLs

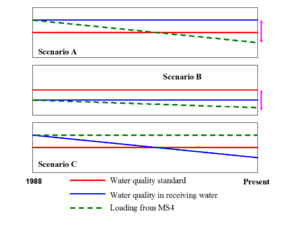

Non-degradation (also called anti-degradation) presents a different target than a TMDL requirement. The figure below illustrates three potential scenarios. In Scenario A, the receiving water body meets water quality standards, but the MS4 is out of compliance with the nondegradation standard. The MS4 must implement BMPs to reduce loading to 1988 levels. In Scenario B, a water was impaired in 1988. If the MS4 implements BMPs to reduce loading to a 1988 level, the receiving water will still be out of compliance with water quality standards. In this situation, a TMDL will be completed and the MS4 must comply with the conditions of the TMDL. Scenario C is potentially problematic. The water body was in compliance with water quality standards and the MS4 has not increased loading since 1988. The receiving water, however, has become impaired and will require a TMDL. The TMDL may place requirements on the MS4. The MS4 may argue that they have met conditions of the TMDL since they have not increased loading from a time when the receiving water met water quality standards.

Scenario C illustrates a need to integrate nondegradation and TMDL approaches for MS4s. In addition, TMDLs may need to contain some language to clarify this situation. Some potential solutions, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive, include the following.

- If a MS4 meets the nondegradation requirement and the receiving water was not impaired in 1988, the MS4 is considered to meet requirements of the TMDL.

- A MS4 must comply with TMDL requirements regardless of whether it meets the nondegradation requirement. The MS4 must therefore demonstrate that BMPs it has implemented achieve the TMDL requirement or implement BMPs to meet the TMDL requirement.

- Modeling approaches for nondegradation and TMDL analysis should be similar. Model inputs, such as phosphorus loading from a specific land use, should be the same for nondegradation and TMDL analysis. BMP efficiency values should be the same for nondegradation and TMDL analysis. Models, model inputs, and BMP efficiencies have not yet been determined. In the interim, MS4s have discretion on these issues, subject to MPCA approval.

- For individual MS4s, it is recommended that the same modeling approaches be used for nondegradation and TMDL analysis.

- A TMDL should specify, to the extent possible, whether water quality in a receiving water met water quality standards in 1988. If data are inadequate to make this assessment, then it is assumed the receiving water was out of compliance in 1988.

Pollutant specific issues

The solutions for many stormwater-TMDL issues may differ for different pollutants. For example, it may be preferable to express the WLA in terms of load per unit area for some pollutants, percent reduction for others, and load for others. This topic has not been adequately discussed.

Analytic tools for calculating WLAs

At this time there is no consistent approach for calculating WLAs. Several analytic models have been used, while flow duration curves have been widely used for fecal coliform TMDLs. The Stormwater Program believes that any recognized and rational modeling approach for calculating loads could be acceptable. Particular application of a model to individual MS4s, including documentation and soundness of methodology, is just as important as the modeling methods. Consistent application of model inputs and assumptions regarding land use are particularly important. A TMDL should adequately describe the modeling methods, inputs, and assumptions.

Use of surrogate measures

For many TMDLs, there are no direct measurements or standards for the pollutant of concern. Examples include impairments for biota, turbidity, and dissolved oxygen. In these cases, a surrogate is typically used. Phosphorus, suspended solids, and flow are often used as surrogates.

The use of surrogates has little impact on a MS4 provided the surrogate is an appropriate indicator of the intended endpoint. This may not always be the case. For example, Minnehaha Creek is impaired for biota. The impairment is likely due to poor habitat and insufficient flow at certain times of the year. A surrogate such as sediment would not be appropriate in this case.

The Stormwater community is interested in the use of surrogate BMPs to meet TMDL requirements. For example, the state of Maine has proposed that WLAs be expressed in terms of percent impervious cover. EPA has not always approved the use of these surrogates. There needs to be more discussion to better determine appropriate surrogates for some types of TMDLs.

Summary of recommended policy

- Because data are generally not available for developing individual WLAs for construction stormwater, it is MPCA’s preference to utilize the construction general permit to manage compliance with a TMDL. When adequate data are available, construction stormwater should be given a separate WLA (wasteload allocation). If a separate wasteload allocation is given, all construction stormwater should receive the same WLA (categorical WLA). If a TMDL provides a separate WLA for construction stormwater, the TMDL should contain specific language about actions that will be required. If a separate WLA is not given to construction stormwater, or if the TMDL does not prescribe additional BMPs to meet the WLA, then MPCA assumes construction activity that follows the conditions of the state general permit and local requirements meets requirements of the TMDL. TMDLs that do not prescribe additional BMPs for construction stormwater should contain the language presented in Section 4.b.ii of this guidance document.

- A TMDL must name each permitted MS4 within the TMDL study area. The TMDL should list the permit number and ID for each MS4. The TMDL must provide a WLA for each permitted MS4. This WLA will be categorical or individual. If data are adequate, individual WLAs should be given to each permitted MS4. TMDLs should be expressed as percent reductions from a defined baseline, in addition to other forms of expressing the TMDL.

- Future discharges, including growth, should be addressed in a TMDL. Guidance is provided in Guidance on what discharges should be included in the Wasteload Allocation for MS4 stormwater at [18].

- Because data are generally not available for developing individual WLAs for industrial stormwater, it is MPCA’s preference to utilize the industrial multisector general permit to manage compliance with a TMDL. Data resulting from benchmark monitoring of industrial stormwater discharges cannot be used to establish a separate WLA for industrial stormwater. When effluent limits are established for an industrial sector, that sector may be given a separate WLA. If a separate wasteload allocation is given for an industrial stormwater sector, all facilities within the sector should be given a single combined WLA (categorical WLA). The preferred form of the load is pollutant (e.g. mass, organisms, etc.) per unit area. If a TMDL provides a separate WLA for industrial stormwater, the TMDL should contain specific language about actions that will be required. If a separate WLA is not given to industrial stormwater, or if the TMDL does not prescribe additional BMPs to meet the WLA, then MPCA assumes industrial activity that follows the conditions of the state multisector general permit meets requirements of the TMDL. TMDLs should contain the language presented in Section 4.b.iv of this guidance document.

- When data allows, discharges covered under individual permits should be given an individual WLA for each permittee. If a TMDL provides an individual WLA for these discharges, the TMDL should contain specific language about actions that will be required and identify the organization(s) responsible for administering those actions. If a separate WLA is not given to these discharges, then MPCA assumes activity that follows the conditions of the permit meets requirements of the TMDL. If a separate WLA is not given to these discharges, the TMDL should contain the following language: “Storm water activities from individually permitted, non-MS4 NPDES/SDS stormwater discharges that are not given an individual WLA will be considered in compliance with provisions of the TMDL if they follow conditions of the individual permit and implement the appropriate Best Management Practices.”