Difference between revisions of "Case studies for stormwater treatment trains"

m |

|||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

Stormwater management at the time consisted of directing surface water runoff (including Bassett Creek) through a large underground tunnel system to reduce flooding problems in the area. This tunnel system discharged directly to the Mississippi River. To handle the considerably higher runoff volume resulting from suburban and freeway development, the originally constructed tunnel was replaced in 1992 in a new alignment several blocks to the south. The old tunnel was left in place for local conveyance. | Stormwater management at the time consisted of directing surface water runoff (including Bassett Creek) through a large underground tunnel system to reduce flooding problems in the area. This tunnel system discharged directly to the Mississippi River. To handle the considerably higher runoff volume resulting from suburban and freeway development, the originally constructed tunnel was replaced in 1992 in a new alignment several blocks to the south. The old tunnel was left in place for local conveyance. | ||

| − | In 1992, the public housing developments occupying the site were the target of a lawsuit charging segregation and isolation of public housing residents. The lawsuit was settled in 1995 through a Decree to determine a re-use plan for the site through a community-based focus group process. The Action Plan developed from these recommendations called for reconnecting the site to surrounding neighborhoods and amenities, demolishing the public housing units, and replacing them with mixed-income housing (25 percent public housing), and a system of parks and open space. The Action Plan was approved in federal court in 1997 and was followed by a [ | + | In 1992, the public housing developments occupying the site were the target of a lawsuit charging segregation and isolation of public housing residents. The lawsuit was settled in 1995 through a Decree to determine a re-use plan for the site through a community-based focus group process. The Action Plan developed from these recommendations called for reconnecting the site to surrounding neighborhoods and amenities, demolishing the public housing units, and replacing them with mixed-income housing (25 percent public housing), and a system of parks and open space. The Action Plan was approved in federal court in 1997 and was followed by a [https://www.jcprd.com/274/Heritage-Park-Master-Plan Master Plan] approved in 2000. The Master Plan called for 900 new mixed-income homes, a combination of rental and for-sale, affordable to families at all income levels. The first units were occupied in November, 2000. |

The challenge at this 145-acre redevelopment site was to incorporate stormwater amenities into the overall site design and best utilize the limited space available. | The challenge at this 145-acre redevelopment site was to incorporate stormwater amenities into the overall site design and best utilize the limited space available. | ||

Revision as of 01:34, 29 December 2022

The following case studies illustrate implementation of stormwater treatment trains.

Contents

Heritage Park, Minneapolis

The Near Northside neighborhood of Minneapolis was originally developed in the late 19th century on land characterized by low-lying swamps, tributary springs, upland seepage and surface runoff areas associated with Bassett Creek. Several generations built low-income housing on wetland and floodplain areas that had been filled and drained in the early 20th century. The early single-family structures failed due to these unstable conditions and were replaced by higher-density rowhouses in public housing projects. These also experienced differential settling of structures, utilities, streets and sidewalks over time due to the poor soil conditions.

Stormwater management at the time consisted of directing surface water runoff (including Bassett Creek) through a large underground tunnel system to reduce flooding problems in the area. This tunnel system discharged directly to the Mississippi River. To handle the considerably higher runoff volume resulting from suburban and freeway development, the originally constructed tunnel was replaced in 1992 in a new alignment several blocks to the south. The old tunnel was left in place for local conveyance.

In 1992, the public housing developments occupying the site were the target of a lawsuit charging segregation and isolation of public housing residents. The lawsuit was settled in 1995 through a Decree to determine a re-use plan for the site through a community-based focus group process. The Action Plan developed from these recommendations called for reconnecting the site to surrounding neighborhoods and amenities, demolishing the public housing units, and replacing them with mixed-income housing (25 percent public housing), and a system of parks and open space. The Action Plan was approved in federal court in 1997 and was followed by a Master Plan approved in 2000. The Master Plan called for 900 new mixed-income homes, a combination of rental and for-sale, affordable to families at all income levels. The first units were occupied in November, 2000.

The challenge at this 145-acre redevelopment site was to incorporate stormwater amenities into the overall site design and best utilize the limited space available.

Project summary

- Location: Minneapolis

- Landscape Setting: Urban

- Drainage Area: approximately 400 acres

- Project Area: 145 acres

- Project Timeline: 2001 to 2007

- Project Cost: $225 million (75 million for infrastructure and 150 million for housing). Cost for stormwater portion of the project was $7.8 million.

Project summary

Stormwater infrastructure for Heritage Park was based on a design that includes a combination of engineered and natural systems set within the development’s park and open space amenities. These serve not only as an effective stormwater treatment system but also restore a sense of place to the traditionally low-income, amenity-poor neighborhood. The stormwater infrastructure for the site treats runoff and non-point source pollution from the 143-acre redevelopment area as well as neighboring residential, commercial, and industrial areas for a total treatment area of roughly 400 acres. The stormwater treatment system is the core of the park and open space component of the project, merging upland and wetland native plant communities with filtration-based processes to remove pollutants. Larger pond systems anchor the park areas while smaller ponds, wetlands and filtration systems are blended into the transportation corridors and edges of the large park areas.

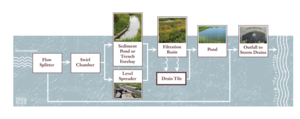

A general stormwater “treatment train” design was used for the Heritage Park project area; each step of the process incrementally cleanses the water further. Rainwater running off the streets and park areas carries sediments and pollutants. The runoff generally enters the system through typical urban catch basins and storm sewers and passes through either grit chambers or into trench forebays for initial removal of large particles. Using a level spreader mechanism, water is then routed to filtration basins planted with wet meadow or wet prairie plant communities. The basins, or galleries, use the cleansing ability of the plantings and soil profiles, reduce velocity, and reduce quantity of stormwater through infiltration and evapotranspiration. Water passes over rock weirs as it moves from one basin to the next, then into ponds for further treatment, as well as enjoyment of the open water amenities. Discharge from the ponds is conveyed downstream through a tunnel to the Mississippi River.

Project description

The treatment system includes both pre-treatment and final treatment Best Management Practices (BMPs).

Pre-Treatment systems

Swirl Chamber: Swirl chambers, also called hydrodynamic separators, are designed to remove large particles and debris from stormwater. Sixteen hydrodynamic separators were installed at Heritage Park. Stormwater is diverted from the conveyance system into the chamber using a flow splitter, through an inlet and across a stainless steel screen whose size was based on site-specific performance standards. The unit has a system bypass that allows excessive stormwater flows to continue downstream via the storm sewer system.

Trench Forebays: Trench forebays are located upslope from filtration basins and are engineered pre-treatment systems that act both as flow spreaders, which reduce the velocity of water before it enters the filtration basin, and sediment collectors. Water then discharges to a filtration basin, either by overtopping the forebay or through drain tile.

Level Spreaders: Level spreaders are located upslope from filtration basins at the transition point between short grass prairie and wetland community to promote even, low-velocity sheet flow into the filtration basins, preventing erosion and enhancing filtration.

Final treatment systems

Filtration Basins: Filtration basins treat stormwater through vegetative and soil filtration. As water moves through the soil profile, the pollutants are retained and the cleansed water moves either laterally through drain tiles or vertically to clay soils and then on to open water features. Vegetation is a key aspect of filtration systems. Above ground biomass slows the lateral movements of water and prevents soil erosion, and root systems also increase filtration rates. The filtration system outflows to conveyance channels or downstream ponds. Filtration systems are effective at removing phosphorus, suspended solids, and pollutants that adsorb to particles, such as heavy metals, but require pre-treatment to prevent clogging.

Stormwater Detention Ponds: Pond systems are effective at attenuating flows and removing suspended solids, floatables, fecal coliform bacteria, and particulate bound pollutants. Small ponds located in the boulevard system collect runoff and provide pre-treatment, retaining pollutants in the permanent water pool before passing water downstream to filtration basins or channels.

Results

The project serves as a model for urban areas for how to integrate stormwater management into the urban fabric and harvest it to create high quality neighborhood amenities. The plantings provide high quality habitat for numerous birds, pollinators and other wildlife.

Costs

Total costs for the planning and installation of stormwater infrastructure and wetlands portion of the project was approximately 7.8 million dollars over a five-year period. The Mississippi Watershed Management Organization was a major contributor for this portion of the project along with additional funding from the McKnight Foundation, Metropolitan Council, Hennepin County, U.S. Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the City of Minneapolis.

Regular maintenance activities are necessary for the system to function as intended. Minneapolis Public Works activities include the clean-out of settleable solids, floatables, trash, and debris from sump structures in the grit chambers by a vacuum truck. The trench forebays also accumulate sediment, which is periodically removed by bobcats or loaders. The vegetation-based treatment systems were fully established in about three years, but must be regularly maintained for peak efficiency. Regular maintenance for the vegetated areas includes removal of invasive plants, pruning, mowing, prescribed burns, and vegetation replacement when needed.

Additional information

- City of Minneapolis (see: fact sheet)

- Heritage Park Near Northside Redevelopment Project website

Maplewood Mall

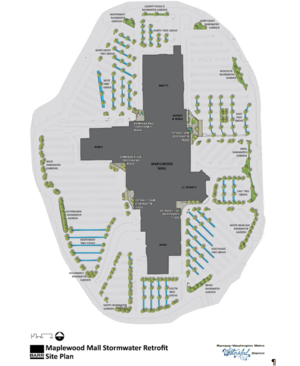

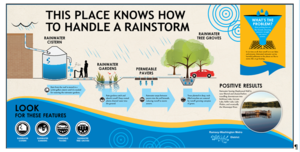

Maplewood Mall, located south of I-694 in Maplewood, is a fully developed mall that contains nearly 70 acres of impervious surfaces, including 35 acres of impervious parking lot. The runoff drains to Kohlman Lake, the most upstream lake of the Phalen Chain of Lakes, which ultimately discharges to the Mississippi River. The lake has been identified as impaired for excessive nutrients and a TMDL implementation plan was approved by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) in 2010.

Ramsey-Washington Metro Watershed District (RWMWD) identified Maplewood Mall as an ideal location within the watershed to provide meaningful particulate and dissolved phosphorus load reductions to Kohlman Lake, as identified in the 2007 Kohlman Creek Subwatershed Infiltration Study. Construction was implemented in four phases, starting in 2009 and ending in 2012.

RWMWD initiated this project for the multiple purposes of reduction in nutrient loading, public education, and creation of a commercial stormwater demonstration project.

Project summary

- Location: Maplewood

- Landscape Setting: Urban - Commercial

- Drainage Area: approximately 70 acres, including 35 acres of parking lot

- Project Area: 35-acre parking lot and 0.5 acres of Maplewood Mall roof

- Project Timeline: 2009 to 2012

- Project Cost: $6,470,000

Description

The following infiltration practices are now actively capturing 67 percent of the runoff from the 35 acre parking lot:

- 6,733 square feet of permeable pavers

- 117 sump catch basins

- 55 rainwater gardens, enhanced with iron aggregate surrounding the underdrains

- 200 trees installed in approximately 1 mile of tree trenches (also called “groves”)

- 175 trees planted in rainwater gardens and end parking islands

- 5,700 gallon cistern that collects runoff from a portion of the Mall rooftop

- Public education kiosks and signs

RWMWD estimates (through modeling and monitoring of the site post-construction) that these BMPs capture 20 million gallons of runoff each year (about two-thirds of the annual runoff volume before the project), reducing the phosphorus loading to Kohlman Lake by 60 percent and sediment loading by 90 percent. See the the project website for more information.

The cistern is a popular component of an interactive educational component of the project. Other public education components include interpretive signage, water features at two entrances to the Mall, rain gardens with interpretive signage at all entrances, tile mural, and hand pumps that allow visitors to release water from the cistern to flow into one of the rain gardens.

Challenges

Development of the project took nearly 5 years as the RWMWD successfully worked through numerous challenges, including the following.

- Compliance with the Minnesota Plumbing Code. The Minnesota Department of Labor and Industry, the regulatory agency responsible for enforcement of the Minnesota Plumbing Code, imposed a number of conditions including a requirement to prevent infiltration near potable water lines, minimization of public contact with water in the cistern, and other conditions that affected the overall project cost.

- Negotiations with multiple property owners. The owner of Maplewood Mall, Simon Property Group, is a strong supporter and partner of the project. However, Simon Property Group is not the sole owner of the parking lot. With the help of Simon Property Group, the RWMWD successfully negotiated agreements with all affected property owners, which did cause delays to the project timeline.

- Parking lot owner’s requirement that changes to the number of parking stalls must comply with City of Maplewood zoning requirements.

- Utility identification discovered several abandoned and/or mis-located utilities that caused adjustments in design and construction.

Costs and funding

The project was designed and constructed by the Ramsey Washington Metro Watershed District, with funding contributed by the following project partners:

- Ramsey Washington Metro Watershed District - $2,000,000

- Clean Water Fund - $1,125,000

- MPCA 319 Grant - $500,000

- TMDL Grant - $1,250,000

- Clean Water Revolving Fund Loan - $1,200,000

- Clean Water Revolving Fund Grant - $397,000

- Total - $6,470,000

Additional information

- Ramsey-Washington Metro Watershed District

- Land and Water, September/October 2012

- Kohlman Lake TMDL Fact Sheet

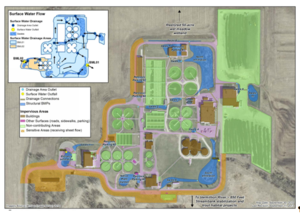

Empire Wastewater Treatment Plant Stormwater Improvements

In 2004 the Metropolitan Council began a project to double the capacity of the Empire Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP), located on the Vermillion River (a DNR-designated trout stream) in Empire Township. The WWTP sits on a 400 acre site in a rapidly developing area of Dakota County. The WWTP process area encompasses 43 acres enclosed by a 500-yr flood berm. The process area previously discharged treated wastewater effluent and unmanaged stormwater directly to the Vermillion River. During the planning stages of the wastewater plant expansion, the Metropolitan Council, along with partners from Friends of the Mississippi River, Dakota County Soil and Water Conservation District, and the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, set project goals of:

- restoration of eroding streambanks and installation of trout habitat features (primarily wooden lunker boxes installed in the toe of the banks) within the Empire WWTP portion of the Vermillion River;

- restoration of a 50-acre seasonally-flooded former corn field to a wet meadow wetland;

- recharge and protection of shallow groundwater;

- management of stormwater within the WWTP process area to result in no discharge of stormwater runoff from a 2-inch rainfall event; and

- design, installation, maintenance, and monitoring of a variety of Low Impact Development (LID) stormwater practices in a treatment train to serve as examples for WWTP visitors and surrounding communities, and to provide performance data to state agencies and stormwater professionals.

Key features of the overall project included diversion of the treated wastewater effluent to the Mississippi River and installation of LID stormwater features within the WWTP process area. The stormwater controls were completed in 2007 and ongoing monitoring has confirmed that there has been no discharge of stormwater runoff from the process area since that time, even after a 5-inch rain event.

Project summary

- Location: Empire Township

- Landscape Setting: Wastewater treatment facility

- Drainage Area: 400 acres

- Project Area: 400 acres

- Project Timeline: 2004 to 2007. Entrance rain garden was reconstructed in 2014-2015.

Project description

Metropolitan Council staff worked with the Friends of the Mississippi River, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, the Dakota County Soil and Water Conservation District, and over 80 volunteers to restore the ecology of restoration sites outside of the WWTP process area. Activities included restoration of streambanks, creation of in-stream trout habitat, restoration of a wet meadow wetland, removal of buckthorn from the floodplain, and planting of native vegetation. Concurrently, the Metropolitan Council worked to design and install LID practices within the 43-acre process area to meet the project goal of no discharge of surface runoff from a 2-inch rainfall.

The schematic at the right illustrates the layout of stormwater practices at Empire WWTF. Components include the following.

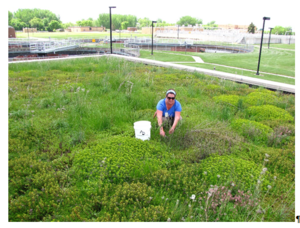

- Green roof installation on the RAS (Return Activated Sludge) building to reduce volume and rate of stormwater runoff and to provide pollinator and bird habitat. This location was selected in part because of its accessibility to visitors as a demonstration project.

- Permeable pavers in five parking areas to reduce the volume of runoff

- Swales to convey the runoff from impermeable surfaces to rain gardens. Swales also allowed some volume reduction through infiltration within the conveyance system.

- Infiltration basins and rain gardens to infiltrate any runoff that overflows from the upstream BMPs of the stormwater treatment train.

Ongoing activities

The Metropolitan Council has established a long term program to provide ongoing maintenance to the stormwater practices, as well as the wet meadow wetland. A contract is issued each five years to a natural resources restoration firm to provide ongoing maintenance of all native plantings within the infiltration basins and the wet meadow wetland. A second specialized contractor provides maintenance and inspection for the green roof vegetation. WWTP staff routinely inspect the pervious pavers, swale culverts, and outfalls to identify areas needing further maintenance.

In 2013, Metropolitan Council staff began installation of monitoring equipment to collect performance data on the stormwater practices. Monitoring includes installation of piezometers and level loggers in the three infiltration basins, installation of a meteorological station, installation of tipping buckets to measure outflow from the green roof, and establishment of monitoring grids on the green roof to assess plant species survival.

Participants and partners

- Metropolitan Council Environmental Services - owner

- Rani Engineering – infiltration basin and swale design

- Luken Architects – green roof design

- Applied Ecological Services – maintenance of wet meadow wetland, native plants and infiltration basin plants

- ADGreenRoof –maintenance, and monitoring of green roof plants,

- Friends of the Mississippi River – streambank planting, buckthorn removal, volunteer organization, and wet meadow restoration

- Dakota SWCD – technical support for stormwater practices, streambank stabilization, and wet meadow restoration

- Minnesota DNR – streambank restoration and trout habitat improvement

Additional information

- http://metrocouncil.org/METC/files/3a/3a32cf96-c872-4c2d-90f9-253af4720a04.pdf

- http://www.fmr.org/projects/empire_wastewater_treatment_plant

- http://www.environmental-initiative.org/our-work/environmentalinitiative-awards/2015-awards-finalists/empire-wastewater-treatment-plant

- http://www.tpomag.com/editorial/2009/03/setting-an-example

Mississippi Watershed Management Organization Backyard

In 2010, the Mississippi Watershed Management Organization (MWMO) began construction of an environmentally state-of-the art facility located on a previous industrial site adjacent to the Mississippi River in Minneapolis. Soil contamination, present from previous industrial activity, required removal or remediation. The MWMO set a goal of demonstrating environmental stewardship with respect to water usage, stormwater management, environmental education, and energy consumption. The objectives of the project included

- zero discharge of stormwater runoff for all precipitation events up to back-to-back 6 inch, 48 hour duration events,

- utilization of 1/3 of the energy consumed by a comparable-sized commercial building,

- creation of a demonstration project for others considering similar features in new construction, and

- creation of a “wet classroom”, an environmental education center for use by individuals, groups, and educators.

Key components of MWMO’s vision were to create a treatment train of stormwater BMPs running through the site’s “backyard” and to connect the urban nature of the Marshall Avenue corridor with the natural areas of the Mississippi River. This case study focuses on these backyard features.

Project summary

- Location: Minneapolis

- Landscape Setting: Urban – commercial/industrial

- Drainage Area: 1.72 acres (includes drainage from both on and off-site)

- Project Area: 1.26 acres on MWMO’s site; 2.34 acres total (includes off-site areas)

- Project Timeline: 2012 - 2013

- Project Cost (backyard components only): $1.6 million total project cost (679,000 for remediation of contaminated sediments; 926,000 for design and construction)

Project description

Construction of the outdoor improvements were complete in 2013. The stormwater management system at MWMO facility schematic shows 19 unique stormwater features that comprise the stormwater treatment train. In addition to managing the runoff from the MWMO facility, these stormwater facilities were designed to incorporate additional runoff from buildings both north and south of the facility, plus all of the runoff from a parking lot south of the facility. The stormwater facilities were laid out in a manner that reflects how a small ravine once existed on the site. Major stormwater management components include

- green rooftop on the new building,

- cistern collecting runoff from the non-green roof portion of the new building for use in irrigating sidewalk trees,

- trench drains below sidewalks collecting and storing runoff for uptake by sidewalk trees,

- vegetated swales collecting runoff from adjacent properties and directing to rainwater garden,

- rainwater garden in parking lot on adjacent property,

- sump catch basins in adjacent parking lot to capture gross pollutants before discharge to a vegetated filter,

- permeable pavers in sidewalk and loading areas,

- gravel bed tree nursery receiving flow from parking areas and rooftop,

- 2 vegetated filters,

- 3 filter media test trenches (3),

- stormwater monitoring stations measuring the rate and quality of runoff, and

- rock swales controlling the discharge velocity to the Mississippi River.

Additional environmental stewardship features of the site include

- outdoor facilities open to the public,

- indoor and outdoor interpretative components,

- indoor water lab that is open to the public,

- removal of over 17,500 tons of contaminated soils,

- geo-thermal heating/cooling system, and

- water efficient fixtures and appliances.

MWMO has ideas for expansion of the stewardship components of their facility, including real-time reporting of energy consumption. Solar panels will be installed on the facility in 2015.

The MWMO plans to install monitoring equipment to observe the system’s performance by 2016. Following adjustments to the initial settings of the treatment train components (weirs), no discharge to the river has been observed.

Project partners

- Mississippi Watershed Management Organization board and staff

- City of Minneapolis

- Hennepin County Environmental Response Fund

- Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development

- Barr Engineering Co.

- Braun Intertec Corporation

- Stearns and Associate

- Sara Nettleleton Architects

- Michael Huber Architects

- Meisinger Construction

- Veit & Co.

- Rachel Contracting

- Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

- Minnesota Department of Natural Resources

- Tony Jaros’ River Garden

- Siweks Lumber Company

Additional information

- SCAPE publication by American Landscape Association of Minnesota. See pages 18-21.

- Met Council publication on MWMO Backyard

- Education and Interpretive Concept Plan 2010

MIDS calculator application

The MWMO site was used in the Minimal Impact Design Standards (MIDS) calculator as an example of a site having BMPs in series. Results of the exercise show that on an annual basis, the BMP configuration at this site removes 97 percent of the stormwater volume, and 99 percent of the total phosphorus and total suspended solids.

Related articles

- Using the treatment train approach to BMP selection

- Scenario for developing a stormwater treatment train for a parking lot

- Scenario for developing a stormwater treatment train for an ultra-urban setting

- Scenario for developing a stormwater treatment train for a site with limited infiltration capacity

- Scenario for developing a stormwater treatment train for a retrofit site

- Scenario for developing a stormwater treatment train for constructed ponds in new development

- Case studies for stormwater treatment trains