Difference between revisions of "Stormwater modeling, models and calculators, and calculating credits-combined"

(Created page with "{{:Introduction to stormwater modeling}} {{:Available stormwater models and selecting a model}} {{:Overview of stormwater credits}} {{:Detailed information on specific models}...") |

m |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{:Introduction to stormwater modeling}} | + | {{alert|This page combines 6 other pages that addressstormwater modeling, models and calculators, and calculating credits. Links to each of those separate articles is provided below. NOTE that combining articles in the wiki essentially pastes the different pages together, which may result in some odd displays where the different pages are pasted together|alert-info}} |

| + | |||

| + | {{:[[Introduction to stormwater modeling]]}} | ||

{{:Available stormwater models and selecting a model}} | {{:Available stormwater models and selecting a model}} | ||

{{:Overview of stormwater credits}} | {{:Overview of stormwater credits}} | ||

Revision as of 15:35, 11 July 2013

{{:Introduction to stormwater modeling}}

Hydrologic, hydraulic, and water quality models all have different purposes and will provide different information. The tables shown at the bottom of this page summarize some of the commonly used modeling software and modeling functions and the main purpose for which they were developed (NOTE: the information in these tables can be downloaded as an Excel file). The tables show the relative levels of complexity of necessary input data, indicate whether the model can complete a continuous analysis or is event based, list whether the model is in the public domain, and for hydraulic models indicate whether unsteady flow calculations can be conducted. For water quality models, the tables indicate whether the model is a receiving waters model, a loading model, or a BMP analysis model. The following definitions apply to the model functions.

- Rainfall-Runoff Calculation Tool: peak flow, runoff volume, and hydrograph functions, only. More complex modeling should utilize hydrologic modeling which incorporate rainfall-runoff functions.

- Hydrologic: includes rainfall-runoff simulation plus reservoir/channel routing.

- Hydraulic: water surface profiles, flow rates, and flow velocities through waterways, structures and pipes. Models that include Green Infrastructure typically also assess how the BMPs managage the water through inflow, infiltration, evapotranspiration, storage and discharge.

- Combined Hydrologic & Hydraulic: rainfall-runoff results become input into hydraulic calculations.

- Water Quality: pollutant loading to surface waters or pollutant removal in a BMP.

- BMP Calculators: spreadsheets that predict BMP performance, only.

Contents

- 1 Defining Model Objectives and Selecting a Stormwater Model

- 2 Summary of Common Stormwater Models

- 2.1 Rational method

- 2.2 HEC-HMS

- 2.3 TR-20

- 2.4 Win TR-55

- 2.5 HEC-RAS

- 2.6 WSPRO

- 2.7 CULVERTMASTER

- 2.8 FLOWMASTER

- 2.9 HydroCAD

- 2.10 PondPack

- 2.11 SWMM-Based programs (SWMM5, PC-SWMM, InfoSWMM, MikeUrban)

- 2.12 XPSWMM

- 2.13 WinSLAMM

- 2.14 P8

- 2.15 BASINS

- 2.16 PONDNET

- 2.17 WiLMS

- 2.18 Bathtub

- 2.19 WASP

- 2.20 SUSTAIN

- 2.21 MIDS Calculator

- 2.22 STEPL

- 2.23 Virginia runoff reduction method

- 2.24 USEPA National Stormwater Calculator

- 2.25 Autodesk Civil 3D

- 3 Table summarizing models by model type

- 4 Table summarizing information for different models

- 5 Definition of credit

- 6 Applicability of credits

- 7 Consistency in calculating credits

- 8 Concerns/disadvantages of crediting

- 9 Is my community ready for credits?

- 10 Adapting credits for local use

- 11 Integrating credits into the local development review process

- 12 General information

- 13 Credits for individual bmps

- 14 Information on using the Minimal Impact Design Standards calculator to calculate credits for volume, phosphorus and total suspended solids

- 15 Other pages

- 16 What is the pre-development condition?

Defining Model Objectives and Selecting a Stormwater Model

Environmental modeling, including stormwater and water quality modeling, is complex given the purpose is to mathematically predict natural processes (USEPA, 2009). Models range from simple spreadsheets that predict a single process such as the runoff from a single storm, to complex simulations that predict multiple, inter-related processes including performance of multiple BMPs. A greater amount of uncertainty is inherent in the more complex models, which results in more complexity in model calibration (WEF, 2012). For example, estimating peak runoff rates is a different problem than estimating the peak elevation of a water body and could require the use of a different model. A model able to estimate phosphorus loading from a network of detention ponds may not be able to model the phosphorus loading from an infiltration pond.

Therefore it is important that modelers select a stormwater modeling tool that is based on both modeling objectives and available resources. The USEPA recommends that the first step in development of a model is to define the objectives (USEPA, 2009). When defining the modeling objectives, the modelers and decision-makers should consider the following (WEF, 2012):

- Regulatory compliance: is the model required for regulatory compliance? Which models are accepted by the regulatory agency?

- Hydrologic process: is the goal to model a single storm event or continuous rainfall? Should the model incorporate infiltration, evaporation, transpiration, abstraction, and other physical processes that reduce the volume of runoff? Is the model required to predict large storm events (for flood control), small storm events (for water quality predictions), or both?

- Land use: is the model required for large rural/agricultural catchments or small urban catchments?

- Area to be modeled: will the model be required to predict stormwater for individual blocks? Or is a larger catchment scale acceptable?

- Intended use: is the intended use for planning purposes, engineering/design, or operational performance?

- Model complexity: will a simple model be sufficient?

- Modeler experience: what is the model-specific expertise of current staff? Is there budget to hire an expert?

The actual process of selecting a model is likely to be an iterative process of model evaluation, adjustments to objectives and/or costs, re-evaluation, and ultimately model selection. Potentially, modelers may select multiple models to meet the objectives of the study. For example one model may be best for hydrology and hydraulics, while another may be best for BMP performance. In these circumstances the modelers should investigate the ability of the models to be linked (USEPA, 2009).

Summary of Common Stormwater Models

The following section describes the most common stormwater models used by stormwater professionals. Use the hyperlinks for additional information on these models.

Rational method

The Rational Method is a simple hydrologic calculation of peak flow based on drainage area, rainfall intensity, and a non-dimensional runoff coefficient. The peak flow is calculated as the rainfall intensity in inches per hour multiplied by the runoff coefficient and the drainage area in acres. The peak flow, Q, is calculated in cubic feet per second (cfs) as Q = CiA where C is the runoff coefficient, i is the rainfall intensity, and A is the drainage area. A conversion factor of 1.008 is necessary to convert acre-inches per hour to cfs, but this is typically not used. This method is best used only for simple approximations of peak flow from small watersheds.

HEC-HMS

HEC-HMS is a hydrologic rainfall-runoff model developed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that is based on the rainfall-runoff prediction originally developed and released as HEC-1. HEC-HMS is used to compute runoff hydrographs for a network of watersheds. The model evaluates infiltration losses, transforms precipitation into runoff hydrographs, and routes hydrographs through open channel routing. A variety of calculation methods can be selected including SCS curve number or Green and Ampt infiltration; Clark, Snyder or SCS unit hydrograph methods; and Muskingum, Puls, or lag routing methods. Precipitation inputs can be evaluated using a number of historical or synthetic methods and one evapotranspiration method. HEC-HMS is used in combination with HEC-RAS for calculation of both the hydrology and hydraulics of a stormwater system or network.

TR-20

Natural Resources Conservation Service Technical Release No. 20 (TR-20): Computer Program for Project Formulation Hydrology was developed by the hydrology branch of the U.S.D.A. Soil Conservation Service in 1964. It was recently updated to allow users to import Atlas 14 precipitation data available from NOAA.

WinTR-20 is a single event watershed scale runoff and routing (hydrologic) model that is best suited to predict stream flows in large watersheds. It computes direct runoff and develops hydrographs resulting from any synthetic or natural rainstorm. Developed hydrographs are routed through stream and valley reaches as well as through reservoirs. Hydrographs are combined from tributaries with those on the main stream. Branching flow (diversion), and baseflow can also be accommodated. WinTR-20 may be used to evaluate flooding problems, alternatives for flood control (reservoirs, channel modification, and diversion), and impacts of changing land use on the hydrologic response of watersheds. A new routine has been added to the program that allows the user to import NOAA Atlas 14 rainfall data for site-specific applications. The rainfall-frequency data will be used to develop site-specific rainfall distributions. The NOAA 14 text files for selected states are available in the Support Materials for downloading and use in WinTR-20 Version 1.11. The NOAA 14 text files and supporting GIS files are packaged in a zip file for each state.

Win TR-55

Technical Release 55 (TR-55; Urban Hydrology for Small Watersheds) was developed by the U.S.D.A. Soil Conservation Service, now the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), in 1975 as a simplified procedure to calculate storm runoff volume, peak rate of discharge, hydrographs and storage volumes in small urban watersheds. In 1998, Technical Release 55 and the computer software were revised to what is now called WinTR-55. The changes in this revised version of TR-55 include: upgraded source code to Visual Basic, changed philosophy of data input, development of a Windows interface and output post-processor, enhanced hydrograph-generation capability of the software and flood routing hydrographs through stream reaches and reservoirs. WinTR-55 is a single-event rainfall-runoff small watershed hydrologic model. The model is an input/output interface which runs WinTR-20 in the background to generate, route and add hydrographs. The WinTR-55 generates hydrographs from both urban and agricultural areas at selected points along the stream system. Hydrographs are routed downstream through channels and/or reservoirs. Multiple sub-areas can be modeled within the watershed. A rainfall-runoff analysis can be performed on up to ten sub-areas and up to ten reaches. The total drainage area modeled cannot exceed 25 square miles.

HEC-RAS

HEC-RAS is a river hydraulics model developed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to compute one-dimensional water surface profiles for steady or unsteady flow. HEC-RAS is an updated version of HEC-2. Computation of steady flow water surface profiles is intended for flood plain studies and floodway encroachment evaluations. HEC-RAS uses the solution of the one-dimensional energy equation with energy losses evaluated for friction and contraction and expansion losses in order to compute water surface profiles. In areas with rapidly varied water surface profiles, HEC-RAS uses the solution of the momentum equation. Unsteady flow simulation can evaluate subcritical flow regimes as well as mixed flow regimes including supercritical, hydraulic jumps, and draw downs. Sediment transport calculation capability will be added in future versions of the model. The HEC-RAS program is available to the public from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. HEC-RAS utilizes the hydrologic results that are developed in HEC-HMS.

WSPRO

WSPRO is a hydraulic model for water surface profile computations developed by the U.S. Geological Survey. The model evaluates one-dimensional water surface profiles for systems with gradually varied, steady flow. The open channel calculations are conducted using backwater techniques and energy balancing methods. Single opening bridges use the orifice flow equation and flow through culverts is computed using a regression equation at the inlet and an energy balance at the outlet. The WSPRO program is available to the public and can be downloaded from the U.S. Geological Survey.

CULVERTMASTER

CulvertMaster is a hydraulic analysis program for culvert design. The model uses the U.S. Federal Highway Administration Hydraulic Design of Highway Culverts methodology to provide estimates for headwater elevation, hydraulic grade lines, discharge, and culvert sizing. Rainfall and watershed analysis using the SCS Method or Rational Method can be incorporated if the peak flow rate is not known. CulvertMaster is a proprietary model that can be obtained from Haestad Methods, Bentley Systems, Inc.

FLOWMASTER

FlowMaster is a hydraulic analysis program used for the design and analysis of open channels, pressure pipes, inlets, gutters, weirs, and orifices. Mannings, Hasen-Williams, Kutter, Darcy- Weisbach, or Colebrook-White equations are used in the calculations. FlowMaster is a proprietary model that can be obtained from Haestad Methods, Bentley Systems, Inc.

HydroCAD

HydroCAD is a computer aided design program for modeling the hydrology and hydraulics of stormwater runoff. Runoff hydrographs are computed using the SCS runoff equation and the SCS dimensionless unit hydrograph. For the hydrologic computations, there is no provision for recovery of initial abstraction or infiltration during periods of no rainfall within an event. The program computes runoff hydrographs, routes flows through channel reaches and reservoirs, and combines hydrographs at confluences of the watershed stream system. HydroCAD has the ability to simulate backwater conditions by allowing the user to define the backwater elevation prior to simulating a rainfall event. HydroCAD is a proprietary model and can be obtained from HydroCAD Software Solutions LLC.

PondPack

PondPack is a program for modeling and design of the hydrology and hydraulics of storm water runoff and pond networks. Rainfall analyses can be conducted using a number of synthetic or historic storm events using methods such as SCS rainfall distributions, intensity-duration-frequency curves, or recorded rainfall data. Infiltration and runoff can be computed using the SCS curve number method or the Green and Ampt or Horton infiltration methods. Hydrographs are computed using the SCS Method or the Rational Method. Channel routing is conducted using the Muskingun, translation, or Modified Puls methods. Outlet calculations can be performed for outlets such as weirs, culverts, orifices, and risers. The program can assist in the determination of pond sizes. PondPack is a proprietary model that can be obtained from Haestad Methods, Bentley Systems, Inc.

SWMM-Based programs (SWMM5, PC-SWMM, InfoSWMM, MikeUrban)

SWMM-Based Programs SWMM is a hydraulic and hydrologic modeling system that also has a water quality component. Please see the full description above for more details on the model. The Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) was originally developed for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1971. SWMM is a dynamic rainfall-runoff and water quality simulation model, primarily but not exclusively for urban areas, for single-event or long-term (continuous) simulation. Version 5 of SWMM was developed in 2005 and has been updated multiple times since. The Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) is a comprehensive computer model for analysis of quantity and quality problems associated with urban runoff. Both single-event and continuous simulation can be performed on catchments having storm sewers, or combined sewers and natural drainage, for prediction of flows, stages and pollutant concentrations. Extran Block solves complete dynamic flow routing equations (St. Venant equations) for accurate simulation of backwater, looped connections, surcharging, and pressure flow. A modeler can simulate all aspects of the urban hydrologic and quality cycles, including rainfall, snow melt, surface and subsurface runoff, flow routing through drainage network, storage and treatment. Statistical analyses can be performed on long-term precipitation data and on output from continuous simulation. SWMM can be used for planning and design. Planning mode is used for an overall assessment of urban runoff problem or proposed abatement options. Current update of SWMM includes the capability to model the flow rate, flow depth and quality of Low Impact Development (LID) controls, including permeable pavement, rain gardens, green roofs, street planters, rain barrels, infiltration trenches, and vegetative swales The SWMM program is available to the public. The proprietary shells, PC-SWMM, InfoSWMM, and Mike Urban, provide the basic computations of EPASWMM with a graphic user interface, additional tools, and some additional computational capabilities.

XPSWMM

XPSWMM is a propriety model that originally began as a SWMM based program. The model developer has developed many upgrades that are independent of the USEPA upgrades to SWMM. Because of these upgrades the two software platforms are no longer interchangeable. XP SWMM does have a function that allows model data to be exported in SWMM format. Comparison of model results between the two softwares will result in similar, but not identical, results.

XP SWMM’s hydrologic and hydraulic capabilities includes modeling of floodplains, river systems, stormwater systems, BMPs (including green infrastructure), watersheds, sanitary sewers, and combined sewers. Pollutant modeling capabilities include pollutant and sediment loading and transport as well as pollutant removal for a suite of BMPs.

WinSLAMM

The Source Loading and Management Model is a stormwater quality model developed for the USGS by John Voorhees and Robert Pitt for evaluation of nonpoint pollution in urban areas. The model is based on field observations of grass swales, wet detention ponds, porous pavement, filter strips, cisterns and rain barrels, hydrodynamic settling devices, rain gardens/biofilters and street sweeping, as either other source area or outfall control practices. The focus of the model is on small storm hydrology and particulate washoff. The WinSLAMM model may be obtained from PV & Associates. Wisconsin data files for input into SLAMM may be obtained from the U.S. Geological Survey, and the model provides an extensive set of rainfall, runoff and particulate solids and other pollutant files developed from the National Stormwater Quality Data Base for most urban areas in the county.

The graphical interface allows users to define both source area and drainage system stormwater control practices using a drag-and-drop interface, and the program and web site provides extensive program help and stormwater quality references.

P8

P8 - Program for Predicting Polluting Particle Passage through Pits, Puddles & Ponds, is a physically-based stormwater quality model developed by William Walker to predict the generation and transport of stormwater runoff pollutants in urban watersheds. The model simulates runoff and pollutant transport for a maximum of 24 watersheds, 24 stormwater best management practices (BMPs), 5 particle size classes, and 10 water quality components. The model simulates pollutant transport and removal in a variety of BMPs including swales, buffer strips, detention ponds (dry, wet and extended), flow splitters, and infiltration basins (offline and online). Model simulations are driven by a continuous hourly rainfall time series. P8 has been designed to require a minimum of site-specific data, which are expressed in terminology familiar to most engineers and planners. An extensive user interface providing interactive operation, spreadsheet-like menus, help screens and high resolution graphics facilitate model use.

BASINS

The Better Assessment Science Integrating Point and Nonpoint Sources (BASINS) model is a multipurpose surface water environmental analysis system developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Office of Water. The model was originally introduced in 1996 and has had subsequent releases in 1998 and 2001. BASINS allows for the assessment of large amounts of point and non-point source data in a format that is easy to use and understand. BASINS incorporates a number of model interfaces that it uses to assess water quality at selected stream sites or throughout the watershed. These model interfaces include:

- QUAL2E: A water quality and eutrophication model

- WinHSPF: A watershed scale model for estimating in-stream concentrations resulting from loadings from point and non-point sources

- SWAT: A physical based, watershed scale model that was developed to predict the impacts of land management practices on water, sediment and agricultural chemical yields in large complex watersheds with varying soils, land uses and management conditions over long periods of time.

- PLOAD: A pollutant loading model.

PONDNET

The PONDNET model (Walker, 1987) is an empirical model developed to evaluate flow and phosphorous routing in Pond Networks. The following input parameters are defined by the user in evaluating the water quality performance of a pond: watershed area (acres), runoff coefficient, pond surface area (acres), pond mean depth (feet), period length (years), period precipitation (inches) and phosphorous concentrations (ppb). The spreadsheet is designed so that the phosphorous removal of multiple ponds in series can be evaluated.

WiLMS

The Wisconsin Lake Modeling Suite (WiLMS) is a screening level land use management/lake water quality evaluation tool developed by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. It is a spreadsheet of thirteen lake model equations used to predict the total phosphorus (TP) concentration in a lake. TP loads can be entered either as point sources or by entering export coefficients for land uses. WiLMS can be downloaded for free at the Wisconsin DNR Web page.

Bathtub

Bathtub is an empirical model of reservoir eutrophication developed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Single basins can be modeled, in addition to a network of basins that interact with one another. The model uses steady-state water and nutrient balance calculations in a spatially segmented hydraulic network, which accounts for advective and diffusive transport and nutrient sedimentation.

WASP

WASP, Water Quality Analysis Simulation Program, is a model developed by the U.S. EPA to evaluate the fate and transport of contaminants in surface waters such as lakes and ponds. The model evaluates advection, dispersion, mass loading, and boundary exchange in one, two, or three dimensions. A variety of pollutants can be modeled with this program including nutrients, dissolved oxygen, BOD, algae, organic chemicals, metals, pathogens, and temperature.

SUSTAIN

SUSTAIN (System for Urban Stormwater Treatment and Analysis Integration) was developed by the USEPA to assist stormwater professionals in developing and implementing plans for stormwater flow and pollutant controls on a watershed scale. SUSTAIN contains seven modules that integrate with ArcGIS. Hydrology, hydraulics, and pollutant loading are computed using EPASWMM, Version 5. Sediment transport is based on HSPF. Modules include:

- Framework manager

- BMP siting tool

- Land simulation module

- BMP simulation module

- Conveyance simulation

- BMP optimization

- Post-processor

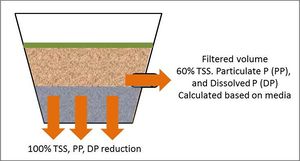

MIDS Calculator

The MIDS Calculator was developed by the MPCA as an Excel-based stormwater quality tool to predict the annual pollutant removal performance of low impact development (LID) BMPs. The calculator will compute the volume reduction associated with infiltration practices plus the TSS and TP reductions for both LID and traditional BMPs, including permeable pavements, green roofs, bioretention, bioretention with underdrain (biofiltration), infiltration basin, tree trench, tree trench with underdrain, swale side slope, swale channels, swales with underdrains, wet swale, cistern/reuse, sand filter, constructed wetland and constructed stormwater pond.

STEPL

The Spreadsheet Tool for Estimating Pollutant Load (STEPL) was developed by the USEPA to calculate nutrient and sediment loads from different rural land uses and BMPs on a watershed scale. STEPL provides a user-friendly interface to create a customized spreadsheet-based model in Microsoft (MS) Excel. It computes watershed surface runoff; nutrient loads, including nitrogen, phosphorus, and 5-day biological oxygen demand (BOD5); and sediment delivery. The annual sediment load (sheet and rill erosion only) is calculated based on the Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE) and the sediment delivery ratio. The sediment and pollutant load reductions that result from the implementation of BMPs are computed using the known BMP efficiencies.

Virginia runoff reduction method

USEPA National Stormwater Calculator

The National Stormwater Calculator is a tool developed by the USEPA for computing small site hydrology for any location within the U.S. It estimates the amount of stormwater runoff generated from a site under different development and control scenarios over a long term period of historical rainfall. The analysis takes into account local soil conditions, slope, land cover and meteorology. Different types of low impact development (LID) practices (also known as green infrastructure) can be employed to help capture and retain rainfall on-site. Future climate change scenarios taken from internationally recognized climate change projections can also be considered. The calculator’s primary focus is informing site developers and property owners on how well they can meet a desired stormwater retention target.

Autodesk Civil 3D

Autodesk Civil 3D includes additional software applications that allow you to perform a variety of storm water management tasks, including storm sewer design, watershed analysis, detention pond modeling, and culvert, channel, and inlet analysis. For more information, link here.

Table summarizing models by model type

This table classifies common models by type of model. The information in this table can be download as an Excel file. Reference or links to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, service mark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency.

Link to this table.

Table summarizing information for different models

Summary of general information for models. The information in this table can be download as an Excel file (Note the links are not updated in the Excel file)

Link to this table.

| Model or tool | Input complexity | Simulation type(s) | Public domain | Unsteady flow | Type of water quality model | Built-in BMPs | TP | TSS | Volume | Comment on use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR-55 | Low | Event | Yes | Rainfall-Runoff Calculation Tools | None | No | No | Replaced by WinTR-55 | |||

| Rational method (equation) | Low | Event | Yes | Rainfall-Runoff Calculation Tools | None | No | No | ||||

| HEC-1 | Medium | Yes | Hydrologic Models | None | Replaced by HEC-HMS | ||||||

| HEC-HMS | Medium | Event or continuous | Yes | Hydrologic Models | None | No | No | ||||

| Win TR-55 (or TR-20 DOS version) | Medium | Event | Yes | Hydrologic Models | None | No | No | Propose to delete the TR-20 DOS version from the list | |||

| Win TR-55 | Low | Event | Yes | Hydrologic Models | None | No | No | ||||

| HydroCAD | Medium | Event | No | Hydrologic Models | Detention ponds and storage chambers | Yes | Yes | No | It appears that HydroCAD can model ponds/storage and assess pollutant loadings, but not removal by BMPs | ||

| HEC-RAS | Medium | Event or continuous | Yes | Yes | Receiving water, Hydraulic Models | None | Yes | No | |||

| HEC-2 | Medium | Yes | No | Hydraulic Models | None | No | No | Replaced by HEC-RAS | |||

| WSPRO | Medium | Yes | No | Hydraulic Models | None | No | No | This is an old model and likely no longer used | |||

| CulvertMaster | Low | Event | No | No | Hydraulic Models | None | No | No | |||

| Flow Master | Low | Event | No | No | Hydraulic Models | None | No | No | |||

| PondPack | Medium | Event | No | No | Detention ponds. PondPack can calculate first-flush volume and aid in designing for minimum drain time, but does not model pollutants | No | No | No | |||

| EPA SWMM | Medium/High | Event or continuous | Yes | Yes | Loading, Receiving Water (limited to first order decay) | Low impact development BMPs including rain barrels, permeable pavers, vegetative swales, bioretention cells, infiltration trenches; traditional BMPs including detention basins, infiltration practices, wetlands, ponds. | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| PC SWMM | Medium/High | Event or continuous | No | Yes | Loading, Receiving Water (limited to first order decay) | Low impact development BMPs including rain barrels, permeable pavers, vegetative swales, bioretention cells, infiltration trenches; traditional BMPs including detention basins, infiltration practices, wetlands, ponds. | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Info SWMM | Medium/High | Event or continuous | No | Yes | Loading, Receiving Water (limited to first order decay) | Low impact development BMPs including rain barrels, permeable pavers, vegetative swales, bioretention cells, infiltration trenches; traditional BMPs including detention basins, infiltration practices, wetlands, ponds. | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| XPSWMM | Medium/High | Event or continuous | No | Yes | Loading, Receiving Water (limited to first order decay) | Rain gardens, green roofs, rain barrels, street sweeping, infiltration trenches, dry detention basins, wet ponds, swales, porous pavement, filter strips | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| MIKE URBAN (SWMM or MOUSE) | Medium/High | Event or continuous | No | Yes | Loading, Receiving Water (limited to first order decay) | Low impact development BMPs including rain barrels, permeable pavers, vegetative swales, bioretention cells, infiltration trenches; traditional BMPs including detention basins, infiltration practices, wetlands, ponds. | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| ICPR | Medium | Event | No | Ponds | No | No | No | Not believed to be a widely used model for stormwater/pollutant modeling | |||

| InfoWorks ICM | High | Event or continuous | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Mike 11 | Receiving water model | ||||||||||

| CivilStorm | Medium | Event | No | Yes | Ponds, low impact development controls | No | No | Yes | |||

| MODRET | Not believed to be a widely used model for stormwater/pollutant modeling | ||||||||||

| WINSLAMM | Medium | Event/continuous for BMPs | No | BMP, Loading | Grass swales, wet detention ponds, porous pavement, filter strips, cisterns and rain barrels, hydrodynamic settling devices, rain gardens/biofilters and street sweeping | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| P8 | Medium | Event or continuous | Yes | BMP, Loading | Detention ponds, infiltration basins, swales or buffer strips, and generalized devices | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| BASINS | Yes | BASINS is a user interface to set up models in WinHSPF, SWAT, SWMM, PLOAD, and GLWF-E. These models are listed here separately. | |||||||||

| QUAL2E/QUAL2K | Medium | Yes | Receiving water | None | Yes | Yes | Receiving water model | ||||

| WinHSPF | High | Event or continuous | Yes | Yes | Loading, receiving water | Nutrient management, Contouring, Terracing, Ponds, Wetlands; USEPA BMP Web Toolkit available to assist with implementing structural BMPs such as detention basins, or infiltration BMPs that represent source control facilities, which capture runoff from small impervious areas (e.g., parking lots or rooftops). | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| LSPC | High | Event or continuous | Yes | Yes | Loading, receiving water | Though developed for HSPF, the USEPA BMP Web Toolkit can be used with LSPC to model structural BMPs such as detention basins, or infiltration BMPs that represent source control facilities, which capture runoff from small impervious areas (e.g., parking lots or rooftops). | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| SWAT | Medium/High | Event or continuous | Yes | Yes | Loading | Model offers many agricultural BMPs and practices, but limited urban BMPs at this time. BMPs related to urban practices include detention basins, infiltration practices, vegetative filter strips, street sweeping, wetlands. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Limited use in urban areas | |

| PLOAD | Low | Event | Yes | Loading | User-defined practices with user-specified removal percentages | Yes | Yes | No | |||

| PondNet | Low | Event | Yes | Loading | Wet detention ponds | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| WASP | High | Event or continuous | Yes | Receiving water | None | Yes | Yes | No | Receiving water model | ||

| WMM | Not believed to be a widely used model for stormwater/pollutant modeling | ||||||||||

| WARMF | Event or continuous | Yes | Loading, receiving water | ||||||||

| SHSAM | Low | Event | No | BMP | Several flow-through structures including standard sumps, and proprietary systems such as CDS, Stormceptors, and Vortechs systems | No | Yes | No | |||

| SUSTAIN | Medium | Event or continuous | Yes | Bioretention, cisterns, constructed wetlands, dry/wet ponds, swales, green roofs, infiltration basins, infiltration trenches, porous pavement, rain barrels, sand filters, filter strips | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Virginia Runoff Reduction Method | Not believed to be a widely used model for stormwater/pollutant modeling | ||||||||||

| MapShed | Medium | Event | Yes | Loading, BMP | Detention basins, vegetated buffer strips, stabilized streambanks, infiltration/bioretention, constructed wetlands, street sweeping | Yes | Yes | Yes | Region-specific input data not available for Minnesota but user can create this data for any region. | ||

| MIDS calculator | Low | Event | Yes | Green roof, bioretention basin (with and without underdrain), infiltration basin, permeable pavement, infiltration trench/tree box, dry swale, wet swale, sand filter, wetland, stormwater pond, user defined | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| EPA National Stormwater Calculator | Low | Event or continuous | Yes | Disconnection, rain harvesting, rain gardens, green roofs, street planters, infiltration basins, porous pavement | No | No | Yes | ||||

| SELECT | Low | Event | Yes | Extended detention, bioretention, wetland basin, swale, permeable pavement, filter, and user-defined | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Center for Neighborhood Technology Green Values National Stormwater Management Calculator | Low | Event | Yes | Green roof, planter boxes, rain gardens, cisterns/rain barrels, native vegetation, filter strips, amended soil, swales, trees, permeable pavement | No | No | Yes | ||||

| Metropolitan Council Stormwater Reuse Guide Excel Spreadsheet | Low | Event | Yes | Computes storage volume for stormwater reuse systems | No | No | Yes | Uses 30-year precipitation data specific to Twin Cites region of Minnesota | |||

| MCWD/MWMO Stormwater Reuse Calculator | Low | Event | Yes | Computes storage volume for stormwater reuse systems | No | No | Yes | ||||

| North Carolina State University Rainwater Harvesting Model | Not believed to be a widely used model for stormwater/pollutant modeling | ||||||||||

| i-Tree Streets | Low | Event | Yes | Trees | No | No | Yes | ||||

| i-Tree Hydro | Low | Event | Yes | Trees, watershed scale | Yes | Yes | Yes | NOTE: Beta version | |||

| RECARGA | Low | Event or continuous | Yes | Bioretention/rain garden and infiltration facilities | No | No | Yes | ||||

| SELDM | Low | Yes | Stochastic | Yes | Not believed to be a widely used model for stormwater/pollutant modeling | ||||||

| MIDUSS | Not believed to be a widely used model for stormwater/pollutant modeling | ||||||||||

| QHM | Not believed to be a widely used model for stormwater/pollutant modeling | ||||||||||

| WWHM | Not believed to be a widely used model for stormwater/pollutant modeling | ||||||||||

| HY8 | Not believed to be a widely used model for stormwater/pollutant modeling | ||||||||||

| Hydraulic Toolbox | Not believed to be a widely used model for stormwater/pollutant modeling | ||||||||||

| SMS | Not believed to be a widely used model for stormwater/pollutant modeling | ||||||||||

| GWLF-E | Replaced by MapShed | ||||||||||

| EPD-RIV1 | Not believed to be a widely used model for stormwater/pollutant modeling | ||||||||||

| CE-QUAL-RIV2 | |||||||||||

| CE-QUAL-W2 | Receiving water model |

Stormwater credit is a tool for local stormwater authorities who are interested in

- providing incentives to site developers to encourage the preservation of natural areas and the reduction of the volume of stormwater runoff being conveyed to a best management practice (BMP);

- complying with antidegradation requirements, including meeting the MIDS performance goal; or

- meeting or complying with water quality objectives, including total maximum daily load (TMDL) wasteload allocation (WLAs). If interested in information on MS4 annual reporting see here.

Definition of credit

There is no universal definition for the term stormwater credit. As used in this manual, credit refers to the stormwater runoff volume or pollutant reduction achieved toward meeting a runoff volume or water quality goal. Examples of goals include meeting the 1 inch volume reduction requirement in the Construction Stormwater General Permit and meeting TMDL pollutant reduction requirements. Credits can be achieved either by an individual BMP or cumulatively with multiple BMPs. Examples include the following.

- A rain garden infiltrates 50,000 cubic feet of water per year. The rain garden receives a credit of 50,000 cubic feet to be applied toward runoff reduction (volume control).

- A rain garden results in the removal of 10 pounds of phosphorus per year from stormwater runoff. The rain garden receives a credit of 10 pounds to be applied toward pollutant load reduction.

- Three rain gardens each remove 10 pounds of phosphorus per year. Each rain garden receives a credit of 10 pounds, resulting in a total credit of 30 pounds.

Credits apply to a single pollutant or to runoff reduction. A BMP may thus generate credits for more than one pollutant. Total credit for a specific pollutant or for runoff reduction must therefore be computed individually for each pollutant or volume of runoff reduced. In the example above, the rain garden generates credits for phosphorus reduction and for volume reduction.

Ideally, stormwater credits are simple to calculate, easy to review and delineate on site plans, and quickly verified in the field.

Applicability of credits

Stormwater credits may be generated for a number of reasons. Credits can be used for the following situations.

- To meet a TMDL WLA or other water quality goal. In this situation, BMPs are implemented to reduce pollutant loads. Each BMP results in a specific reduction in loading, which equates with the credit for that BMP. The cumulative reduction in loading achieved with all BMPs is the cumulative or total credit.

- To meet the Minimal Impact Design Standards performance goal. The MIDS performance goal is intended to achieve pre-development (pre-settlement) conditions, thereby resulting in compliance with antidegradation requirements. As with the TMDL example, each BMP receives a credit and the cumulative credit is the sum of individual BMP credits.

- To provide incentives to site developers to encourage the preservation of natural areas and the reduction of the volume of stormwater runoff being conveyed to a best management practice (BMP).

- To reduce costs associated with structural stormwater BMPs. For example, sizing requirements for a wet pond may be reduced if volume reduction credits are generated upstream of the pond. An example is increasing forested area upstream of the pond, which results in decreased runoff amounts and reduced sizing requirements.

- To supplement the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Construction General Permit (CGP) or be used for projects not covered under the CGP.

- As part of the financial evaluation under a local stormwater utility program, similar to the Minneapolis approach.

Although not explicitly allowed under the current MPCA CGP, there are situations where a local authority could create a water quality credit system which does not conflict with the CGP. For example, a local authority that requires a Water Quality Volume that is greater than the CGP water quality volume, could apply credits against the difference between the two volumes. Another situation appropriate for credits could be retrofit projects that do not create new impervious surfaces. These projects are not subject to permanent stormwater management requirements of the CGP.

Consistency in calculating credits

One concern with credits is that two different entities may calculate a credit for the same BMP in different ways or using different assumptions or values. It is important that credits be calculated consistently from one entity to the next. For example, one entity may assume a phosphorus removal efficiency of 50 percent for a wet pond, while another entity may assume a removal efficiency of 60 percent, even though the two ponds may be similar in design. To minimize inconsistencies in calculating credits, this manual provides recommended values to be used for calculating credits for BMPs. These recommended values assume the BMPs are properly designed, constructed and maintained. Design, construction, maintenance, and performance assessment are discussed for each BMP in this manual. Design sections include design specifications where applicable.

Concerns/disadvantages of crediting

Stormwater credits provide a relatively simple process for estimating progress toward reducing stormwater volume and pollutant loads. There are some drawbacks to the credit process however, including but not limited to the following.

- Credits must be applied consistently. Specific values for the effectiveness of stormwater bmps vary widely in the literature.

- Interpretation of credits can be challenging, particularly when treatment trains are employed

- Credits vary with time. This includes event, seasonal, and long-term variability. For example, the effectiveness of bmps diminishes over time if the bmps are not properly maintained.

- Credits do not always align with water quality objectives. For example, if a pollutant reduces total phosphorus (TP) by 50% but TP in the influent to a bmp is 0.50 mg/L, the effluent of 0.25 mg/L is still well above surface water standards (typically 0.04-0.090 mg/L).

- Conversely to the previous bullet, bmp credits will be overestimated when influent pollutant concentrations are very low, since bmps cannot effectively remove pollutants below a certain concentration. For example, if influent TP concentration is 0.05 mg/L, applying a 50 percent reduction gives an effluent of 0.025 mg/L, which is not achievable for most bmps.

Is my community ready for credits?

Experience in other states has shown that it can take a while for both local plan reviewers and engineering consultants to understand and effectively use credits during stormwater design. Adoption of credits by a local regulator is particularly difficult in communities where stormwater design occurs long after final site layout, giving designers or plan reviewers little chance to apply the better site design techniques at the heart of the credit system.

The following four ingredients appear to be important in establishing an effective local credit system:

- Strong interest and some experience in the use of better site design techniques

- A development review process that emphasizes early stormwater design consultations during and prior to initial site layout

- Effective working relationships between plan reviewers and design consultants

- A commitment by both parties to field verification to ensure that credits are not a paper exercise.

Adapting credits for local use

If a community feels it has many of these ingredients in place, it is ready to decide whether to offer some or all of the credits described in this chapter. The first step in the adoption process is to review each stormwater credit to ensure whether it is appropriate given local conditions and review capability. Plan reviewers should pay close attention to how credit conditions and restrictions will be defined. It may be advisable to establish a team of local consulting engineers, plan reviewers and contractors to test out the proposed credits on some recently submitted site plans to make sure they are workable. Future plan review conflicts can be avoided when designers and plan reviewers agree on how credits will be handled in the local development review process.

Integrating credits into the local development review process

Stormwater credits need to be explicitly addressed during three stages of the local development review process, as shown below:

- Feasibility during concept design

- Confirmation in final design

- Verification at final construction inspection

The first stage where credits are considered is during initial stormwater concept design prior to site layout. The designer should examine topography and flow patterns to get a sense for how stormwater can be distributed and disconnected across the site, and explore opportunities to orient lots, grading or conveyance to maximize use of better site design techniques in the proposed site plan. While stormwater credits can be applied to any kind of site, they are ideally suited for low density residential development, particularly when open space or conservation designs are planned. Communities may also elect to offer additional stormwater credits to promote adoption of innovative practices such as green rooftops, soil compost amendments, permeable pavements, and stormwater planters.

Once better site design techniques are incorporated into the site plan, the designer can delineate the approximate areas at the site that are potentially eligible for stormwater credits, making sure that credit areas do not overlap. Ideally, proposed credit areas are drawn directly on the stormwater element of the site plan. Next, the adjusted Vwq is computed, and the remaining elements of the BMP treatment system are sized and located. The local review authority then checks both the credit delineations and computations as part of the review of the stormwater concept plan.

The credits are reviewed a second time during final design to confirm whether they meet the site-specific conditions outlined earlier in this chapter (e.g., slope, contributing drainage area, flow path lengths, etc). The designer should be able to justify the precise boundaries of each credit area on the plan, and indicate in the submittal whether any grading or other site preparation are needed to attain credit conditions (this is particularly important for rooftop disconnection and grass channel credits). Designers should be encouraged to use as many credits as they can on different portions of the site, but plan reviewers should make sure that two or more credits are not claimed for the same site area (i.e., no double counting). Reviewers should carefully check the delineation of all credit areas, make sure flow paths are realistic, and then approve the adjusted Vwq for the site. In addition, the plan reviewer should check to make sure that any required easements or management plans associated with the credit have been secured prior to approval.

Field inspection is essential to verify that better site design techniques used to get the stormwater credits actually exist on the site and were installed properly. This is normally done as a site walk through as part of the final stormwater inspection at the end of construction. To ensure compliance, communities may want to set the value of performance bond for the stormwater system based on the unadjusted Vwq for the site (pre-credit) to ensure better site design techniques are installed properly.

- The Simple Method for estimating phosphorus export

- Recommendations and guidance for utilizing P8 to meet TMDL permit requirements

- Recommendations and guidance for utilizing WINSLAMM to meet TMDL permit requirements

- Recommendations and guidance for utilizing the MIDS calculator to meet TMDL permit requirements

- Guidance and examples for using the MPCA Estimator

General information

Credits for individual bmps

- Calculating credits for bioretention

- Calculating credits for green roofs

- Calculating credits for infiltration basin

- Calculating credits for permeable pavement

- Calculating credits for tree trenches and tree boxes

- Calculating credits for stormwater ponds

- Calculating credits for stormwater wetlands

- Calculating credits for sand filter

Information on using the Minimal Impact Design Standards calculator to calculate credits for volume, phosphorus and total suspended solids

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using bioretention with no underdrain BMPs in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using bioretention with an underdrain BMPs in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using swale without an underdrain as a BMP in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using swale with an underdrain as a BMP in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using swale side slope as a BMP in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using wet swale as a BMP in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using sand filter as a BMP in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using trees as a BMP in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using trees with an underdrain as a BMP in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using green roofs as a BMP in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using permeable pavement BMPs in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using stormwater pond as a BMP in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using stormwater wetland as a BMP in the MIDS calculator.

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using Other as a BMP in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using infiltration basin/underground infiltration BMPs in the MIDS calculator

- Requirements, recommendations and information for using Harvest and re-use/cistern as a BMP in the MIDS calculator

Other pages

The Manual also contains information on models that can be used to calculate credits for volume and pollutants. Information on models is found on the following pages.

- Available stormwater models and selecting a model

- The Simple Method for estimating phosphorus export

- The original Manual contained credit information for Better Site Design.

What is the pre-development condition?

When a requirement exists to match runoff rate or volume to “pre-development conditions,” there is a range of options that could be applied to define land cover conditions. This range goes from pre-settlement, which assumes land is in an undeveloped condition, to the land use condition immediately prior to the project being considered, which assumes some level of disturbance in the natural landscape has already occurred. Interpretations of this variation from Scott County, Project NEMO, Dane County (WI), and the USDA-NRCS ere used to lay out the range of approaches that local units can use when applying this criterion. Please note that selection of a pre-development definition should occur only after an evaluation of the hydrologic implications of the choice is performed.

Pre-settlement conditions

The most conservative assumption for pre-development conditions is the assumption that the land has undergone essentially no change since before settlement ( Pre-settlement conditions). In this case, a meadow or woodland in good condition is commonly used to portray a “natural” condition. The following table shows the curve numbers used when this situation is applied using TR-55. Similar hydrologic characteristics would be applied when using other models.

Curve number for use with pre-settlement conditions.

Link to this table

| Runoff Curve Number* | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hydrologic Soil Group (HSG) | Meadow | Woods |

| A | 30 | 30 |

| B | 58 | 55 |

| C | 71 | 70 |

| D | 78 | 77 |

* Curve numbers from USDA-NRCS, Technical Release 55

Conditions immediately preceding development

On the other end of the pre-development definition is the assumption that land disturbance has previously occurred with the land use in place at project initiation. This is the definition used under most circumstances by the MPCA in the Construction General Permit (CGP). Under this scenario, runoff assumptions after construction need to match those of the land use prior to the development using matching curve numbers or runoff coefficients. The new project could possibly improve runoff conditions, if the prior land use did not accommodate any runoff management. That is, implementation of good runoff management to an area that had previously developed without it would likely reduce total runoff amount compared to existing development. Note that the MPCA could alter its definition of pre-development under certain circumstances, such as a total maximum daily load (TMDL) established load limit.

NRCS (TR-55) notes that heavily disturbed sites, including agricultural areas, curve numbers should be selected from the “Poor Condition” subset under the appropriate land use to account for common factors that affect infiltration and runoff. Lightly disturbed areas require no modification. Where practices have been implemented to restore soil structure, no permeability class modification is recommended.