Contents

Nature of the cold climate problem

Hydrology of melt

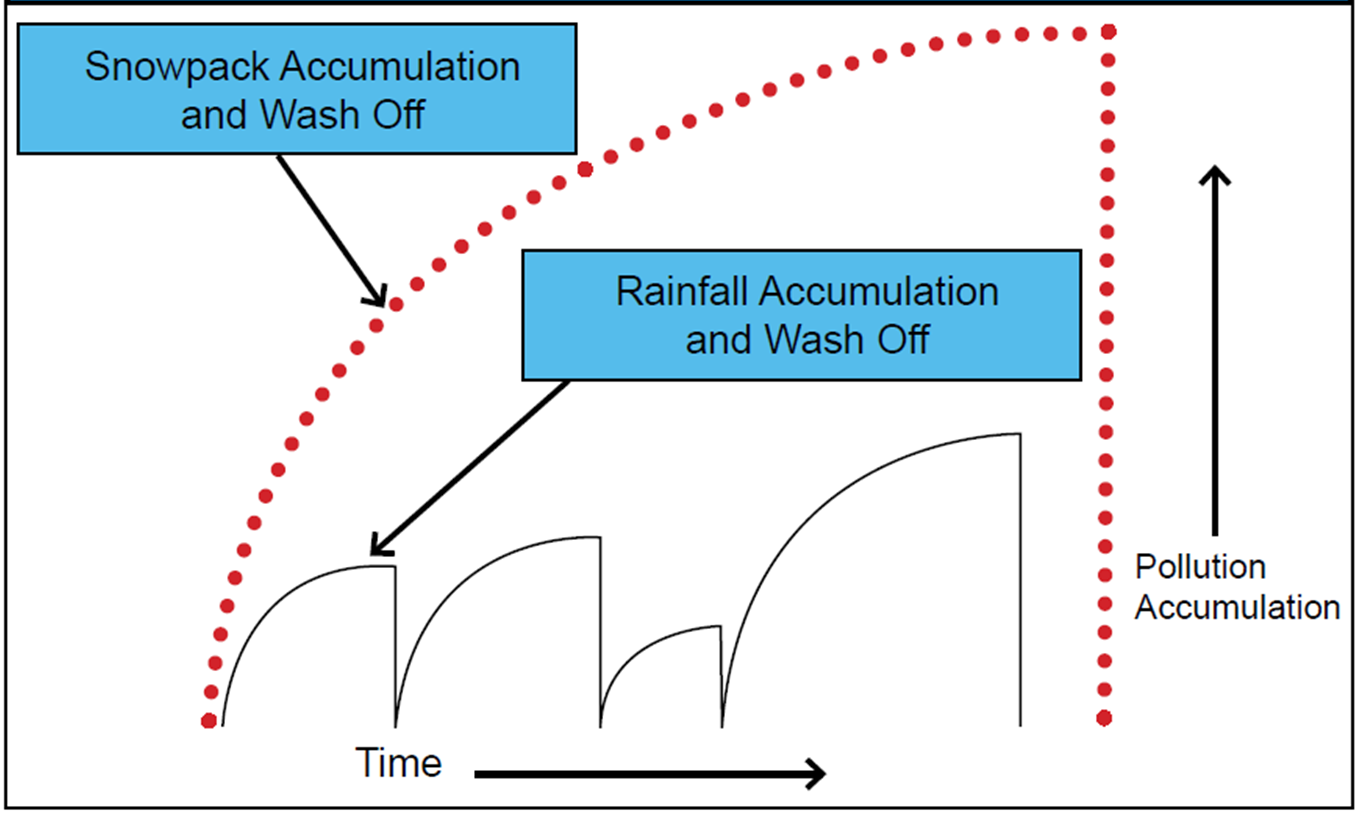

The heart of the problem with snowmelt runoff is that water volume in the form of snow and ice builds for several months and suddenly releases with the advent of warm weather in the spring or during short interim periods all winter long. The interim melts generally do not contribute a significant volume of runoff when compared to the large spring melt. Note that snowmelt peaks are substantially less than those from rainfall, but the total event volume of a snowmelt, although it occurs over a much longer period, can be substantially more. Ignoring the contribution of these large, spring melts to the annual runoff and pollution loading analysis could be a major omission in a watershed analysis. This type of comparison also shows why facility design is critical to the proper quantity and quality management of this meltwater.

In the figure above, note that pollutants accumulate in the snowpack during winter and are then released during spring snowmelt. This differs from rainfall-generated runoff, in which build-up and wash-off of pollutants is a continuous cycle.

This behavior of seeing a major portion of the annual runoff occur during the relatively short period in the year when the snowpack melts is typical of cold climates. Factors influencing the nature of this melt and the speed with which it occurs include solar radiation, the distribution of snow cover, the addition of de-icing chemicals to the pack, and the amount of freeze-thaw cycling.

The source area for snowmelt plays a critical role in both the hydrologic and water quality character of snowmelt runoff. Roadways and large paved surfaces like commercial parking lots are the direct recipients of fast and efficient snow removal. This can occur by plowing, which can include total site removal or relocation off of the surface, and/or chemical-induced (salt) melting. Because of the need to promote safety, obtaining an ice- and snow-free surface is a focal point for winter management of these surfaces. As a result, these surfaces generate numerous loading events every time it snows or even in anticipation of a snowfall, since pre-icing application of salt can be a common practice. By the time the major spring melt occurs, many of these surfaces are free of snow and ice. However, in many instances the snow that has been removed is piled or plowed close to the surface and flows onto it. At this time it becomes part of the urban drainage system or is stored in a location where it immediately enters the drainage system upon melt. These road and parking surfaces can be a significant source of many of the most contaminating pollutants associated with urban runoff.

A second category of importance to snowmelt runoff is the area immediately adjacent to the roadway or parking surface. This is the area that is generally the most significant source of poor water quality during a melt. Because snow is plowed and piled in these areas, they accumulate both equivalent water volume and pollutants for an extended period of time over the winter. This material is then available for release and migration over a several week period in the spring. This critical area is usually contained within about 25 feet of the paved surface and easily flows to the storm drain system as it melts. Sometimes, as in commercial parking or roadside piles, the snow is actually sitting on an impervious surface.

The final contributing area to meltwater runoff is the less developed residential, open space, low density area typical of suburban watersheds. An example of these includes areas well removed from roadways and high traffic. Snowmelt from these areas can be large contributors of meltwater volume, but the quality of the melt is better than from roadways and parking areas. Typically a fair amount of the initial meltwater soaks into the ground and can continue to do so as long as the rate of melt does not exceed the infiltration capacity of the soil. If sufficient snowpack is available, saturation can occur, leading to this portion of the watershed acting as an impervious surface.

The relative contributions of the three principal areas shown in these photos cannot be generalized because of the mix that occurs within any watershed. However, the characteristics of a specific watershed and the management approach needed as a result can be estimated from the mix. That is, a densely developed urban area will have more roadways and impervious parking surfaces typical of paved surfaces with heavy traffic, whereas a suburban neighborhood or rural setting will be a larger source of volume.

Snowpack builds throughout the winter and increases in moisture content as the winter season draws toward melt. When meltwater exits the snowpack, it moves into the ground or over the land surface. A very important part of snowmelt management for both quantity and quality depends upon this behavior and the variations it takes. It is very common for the first part of the melt to soak into the ground. However, at some point in the melt sequence, particularly when there is a deep snowpack at the on-set, the ground can become saturated and turn a pervious, non-contributing part of the watershed into an essentially impervious surface from which all additional melt runs off. Hydrographs from melt events will typically show a period of little to no runoff, even though the melt rate might be high, followed by accelerating flow as the ground no longer soaks in the melting snowpack. Recognizing this behavior could be important for early runoff and quality management.

Quality of melt

The water quality problems associated with melt occur because the large volume of water released during melt and rain-on-snow events not only carries with it the material accumulated in the snowpack all winter, but also material it picks up as it flows over the land’s surface. The winter accumulation can occur directly on a standing snowpack or on the side of a roadway where it is plowed. In either case, the material builds for several months prior to wash-off. Since snow is a very effective scavenger of atmospheric pollutants, literally any airborne material present in a snow catchment will show up in meltwater when it runs off. Add to this the material applied to, or deposited upon the land surface, for example to melt snow or prevent cars from sliding, and the wide range of potential pollutants becomes apparent. As with the volume of meltwater, a major portion of annual pollutant loading can be associated with spring melt events.

The conventional pollutants of concern for most urban runoff situations are supplemented in meltwater runoff by additional contaminants added during the winter. The solids, nutrients, and metals present during the summer are joined by increased polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and hydrocarbons from inefficient and increased fuel combustion; by salt and increased solids from anti-skid application; and by cyanide that has been added as an anti-caking additive to salt. Pesticide and fertilizer runoff and organic debris (leaves, grass clippings, seeds) are less of a concern during the winter.

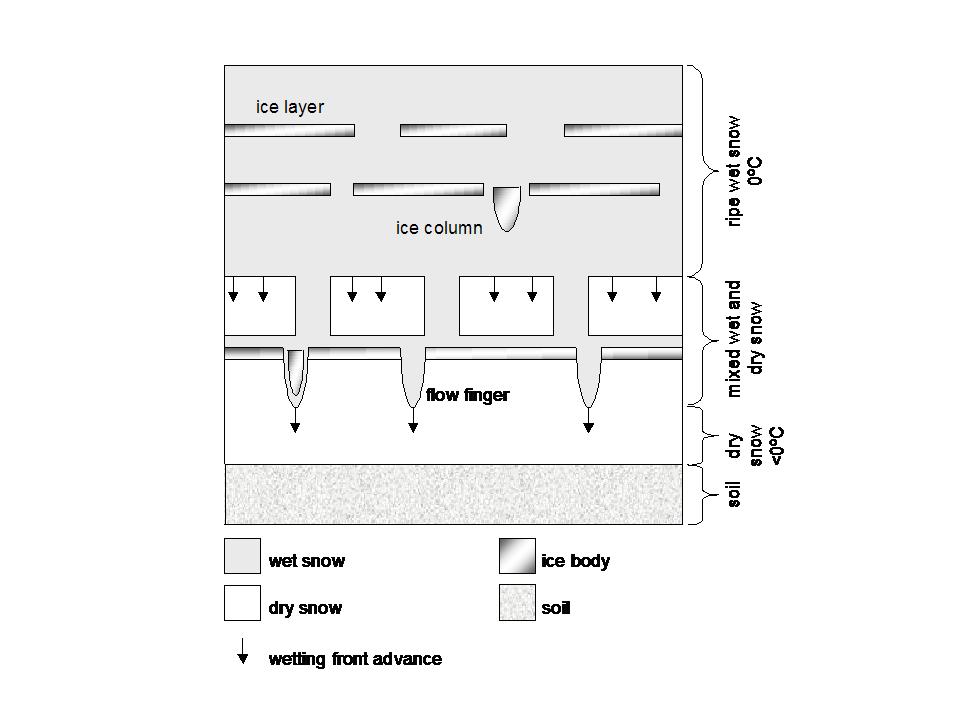

The complex melting pattern that occurs within a snowpack results in the release of pollutants at different times during the melt, further complicating an already difficult management scenario. The variability of snow character and the repeated freeze-thaw cycles that occur throughout a long winter create a very heterogeneous snowpack, with many different flow paths available for melt water to move along. The freeze-thaw cycles also result in the re-crystallization of snow and the subsequent exclusion of “impurities” to the outside edge of the crystals, whereupon they become available for wash-off by the melting front as it passes. The process has been called by many different names, including “preferential elution,” “freeze extraction,” and “first flush.” This melting sequence becomes a very important part of snowmelt quality management because the practices used may or may not come close to treating a particular target pollutant depending upon where in the sequence it is captured.

Melt water can move downward in a snowpack through different flow-paths around “dry” snow and ice layers caused by repeated freeze-thaw cycles. As this water moves through, it picks up or mobilizes soluble ions that have pushed to the edge of ice crystals. Through this process, the snowpack cleanses itself of soluble contaminants that become available in the first phases of the melt, yielding a highly soluble, acidic and perhaps toxic (to animal and plant-life) runoff volume. Later in the event, melt water from the snowpack is depleted in these soluble contaminants, but water flow can be at its highest. Energy levels are only high enough to move fine- to medium-grained particulates when the snowpack allows their passage, leaving behind the coarser-grained material. The coarser material is available for wash-off during the higher energy spring rainfall events, and becomes a major source of contamination at that time. Alert sweeping can pick this coarse material up from paved surfaces if there is an opportunity between the departure of snow and the first rains.

There are important management implications of the preferential elution (or chemical dissolution) process. The graphic shows that the early part of the melt involves the very efficient elution of soluble constituents (Cl, dissolved metals and nutrients, dissolved organics, e.g.) at the crystal edges, resulting in a substantial release of the soluble component of a snowpack, often resulting in a “shock” effect as these pollutants reach a receiving water body. Following the release of solubles is a period when much of the liquid volume of the snowpack releases (skewed toward the earlier part of the mid-melt event) and carries with it the remaining solubles along with the beginning portion of finer-grained solids and associated contaminants (hydrophobic PAHs, e.g.). This mid-melt period generally has the largest portion of water runoff associated with the melt, and the mobilization of solids begins and continues as long as sufficient energy is available to move the finer particles, leaving behind the larger particles.

| General Pollutant Movement from a Snowpack |

| Early | Middle | Late |

|---|---|---|

| Character | ||

| High soluble content | Remaining solubles, beginning of fine- to medium-solids | High solids content |

| Low runoff volume, early infiltration | Large runoff volume | Large runoff volume (especially if rain-on-snow occurs), saturated soils |

| Initiated by chemical addition and/or solar radiation | Largely driven by solar radiation, aided by salt | Solar driven |

| Land Use | ||

| Low density | High density | High density |

| Residential/neighborhood | Roads, parking lots | Roads, highways |

| Open space | Snow storage sites | Commercial |

| BMP Focus | ||

| Infiltration | Pre-treatment (settling) | Pre-treatment (settling) |

| Dilution | Volume control | Filtration |

| Pollution prevention (salt, chemical application) | Detention/settling | Volume control |

| Retention | Pollution prevention (surface sweeping) | |

| Wetlands/vegetation (infiltration, biological and soil uptake) | Detention/settling | |

| Diffuse runoff paths | Wetlands/vegetation (filtration, settling) | |

Part of the severity of the water quality problem associated with melt is that it occurs when the hydrologic system is least able to deal with it. Routine assumptions on biological activity, aeration, settling, and pollutant degradation are altered by the cold temperatures, cold water and ice covered conditions that prevail for many months. An end of the season rain-on-snow event often presents the worst-case scenario when rain falls onto a deep, possibly saturated snowpack. The movement of a well defined, rapidly moving wetted front through the snowpack results in the mobilization of soluble constituents, plus the energy associated with the rainfall is sufficient to mobilize the fine-grained or possibly larger solids and associated contaminants. This wave of melt also washes over urban surfaces and picks up material that has been deposited on these surfaces all winter. Comprehensive reviews of the quality of snowmelt are presented in many of the references at the end of this chapter.

The toxicity of the meltwater and the effects that these chemicals have on various receiving waters and related biological resources is still poorly understood. It is understood that meltwater can be extremely concentrated in many different toxic substances (metals, PAHs, organics, free cyanide, chloride). However, little is known about the impact of these substances on streams, lakes, groundwater and wetlands, and even less about their impact on plants, invertebrates, fish and other biological life.

The effects of road salting, especially the conservative element chloride (Cl), becomes increasingly important as the number of vehicles in the state dramatically increases. With the increased number of vehicles comes a need to provide ever safer traffic-ways, which translates into ice-free roads for several months in cold climates. The increase in road salt has even led the Government of Canada to recommend the inclusion of Cl as a toxic substance because of the impact of this chemical on ground and surface waters. Associated with Cl is the anti-caking salt additive, sodium ferrocyanide, which is used commonly in Minnesota. Although not toxic itself, ferrocyanide can break down to free cyanide, which is extremely toxic at low levels. Recent data collected in Minnesota has shown that chemicals associated with salting operations (sodium, chloride and cyanide) can reach very high levels in runoff from sites where salt is stored and handled, even if recommended handling procedures are followed.

Groundwater impact

The most damaging meltwater component affecting groundwater appears to be the two elements associated with the most commonly used road salt - sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl). The damage begins at the soil interface where Na can displace Ca and Mg and disrupt the physical structure of the soil column. Chloride can lower pH and dissociate heavy metals into more soluble and mobile forms. Although both of these chemicals can continue to migrate downward, it is mostly the Cl that presents a major threat. Much more data are needed before the complexity of the Cl threat can be fully understood. Although the threat is very real and has been documented with groundwater data in many places, in other places even within the same region, the threat is variable.

Wetland, open space and biological impacts

There are scant data available on the impact of meltwater on wetland systems and associated open space areas. This information is critical when the use of “natural systems” for runoff management is increasingly promoted. Among the impacts are species shifts to less desirable species, increased toxicity to various biota, and decreased diversity. Some vegetative species are recommended for use in various surface water management approaches in Minnesota. A very good resource on the topic has been produced through MPCA, entitled Plants for Stormwater Design - Species Selection for the Upper Midwest (Shaw and Schmidt, 2003).

Effects of climate change

According to University of Minnesota Professor and Extension Climatologist/Meteorologist Dr. Mark Seeley, sufficient data exist to support recently observed trends of climate change in Minnesota. These trends, as well as others collected from the global climate research community (i.e., the National Academy of Sciences U.S. Global Change Research Programs, the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations International Panel on Climate Change, and numerous national and international universities) indicate that the following changes are likely to occur in the state:

- warmer winters;

- higher minimum temperatures;

- greater annual precipitation with

- more snowfall, but faster melting and smaller snowpacks;

- more days with rain (possibly when snow present);

- local weather less predictable and forecast less accurate;

- local weather more variable with longer periods of drought and wetness;

- local weather more severe (more “storms of the century”);

- stormwater and flood design criteria changes to reflect new conditions more accurately;

- less annual runoff, frequent summer droughts; and

- lack of ice cover or thinning of cover, decreased annual freshet (high spring flows), warmer water temps, loss of wetlands, poorer water quality.

The result of this phenomenon on the character of snow accumulation and melt could be substantial in the long-term. It seems clear that

- snow will fall in changed patterns and that which falls will accumulate less;

- that snowfall terminus lines will shift northward and upward in elevation;

- that the mix of ice storms and rain-on-snow will increase;

- that the timing and rate of snowmelt will vary from current conditions; and

- that the likelihood of flooding events associated with rainfall during spring melt will increase.

This is a future that could also imply more chemical use to provide road safety, less chance for effective storage of snowmelt for later use, and altered annual water balances. It is also assured that any scenario for the future will include a substantial amount of uncertainty in both climatic factors and social factors as solutions to perceived and real problems are implemented.

Based on this evidence, techniques for managing stormwater under these changing conditions should be considered.

- Managers should address cold climate conditions and the pollutants associated with them.

- Higher levels of treatment (i.e., pollutant removal) for meltwater, perhaps in an SWPPP, based on land use, snow management plans, and anticipated pollutant loads of priority pollutants (sediment, chlorides, nutrients) and the waters to which they discharge should be considered.

- Implementation of a “snow management plan” should be considered.