This section of the manual is currently under review.

This section introduces national and international research and experience on stormwater practices maintained in cold climate regions, and presents principles for adapting BMPs to provide effective pollutant removal and runoff control during cold-weather months. It also introduces some recent findings from within Minnesota on the impact of climate change on stormwater and meltwater runoff. For more information on this topic, see Chapter 5 of MPCA’s Protecting Water Quality in Urban Areas.

Minnesota stormwater managers must recognize that runoff from snowmelt has special characteristics, and that BMP design criteria addressing only rainfall runoff might not work well during cold periods. This becomes a major problem because a substantial percentage of annual runoff volume and pollutant loading can come from snowmelt.

Contents

- Challenges in engineering and design - complicating factors for cold climate design

- Design adaptations for cold climates

- Preliminary considerations for design sheets based on cold climate performance

- References

Challenges in engineering and design - complicating factors for cold climate design

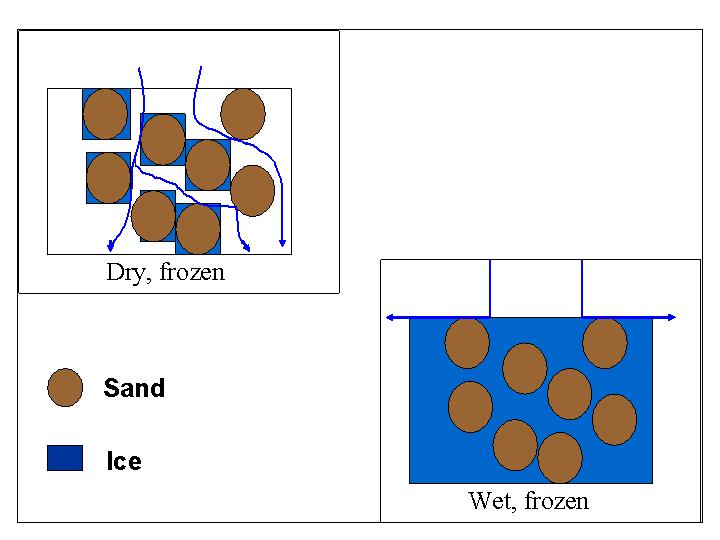

The physical and chemical processes under way in a snowpack present an extremely complicated and variable set of phenomena. The freeze-thaw cycle and the elution of chemicals that it drives have been understood for many years, but details on the migration and management of the many chemicals of concern from the snowpack are seldom pursued by runoff managers. In 1997, the Center for Watershed Protection produced a design manual intended to address many of these problems. One of the items reported in that manual was a survey of cold climate stormwater managers asking what the challenges were that they faced. A special session was held at the 2003 Maine Cold Climate Conference during which practitioners were asked the same question. Also, a public input meeting during the development of this Manual noted the basic problems of managing stormwater in cold climates were still of concern to managers. While no magic new practices exist to treat this runoff, some adaptation of our existing approach to design and snow management could be the key to addressing this situation in cold climates.

Design adaptations for cold climates

Unified sizing

How can design criteria be recommended such that everyone uses the same approach? A methodology for determining the snowmelt volume to add into the runoff calculations is suggested as input independent of whatever method is used for defining “water quality volume.” The unified sizing criteria for ponding includes adaptations that would account for less effective cold weather treatment, if possible. This may be achieved through initial design or through retrofit of existing facilities. This runoff volume should also be considered in other BMPs besides ponding and in the use of any kind of credit for meltwater design.

Water quality sizing of snowmelt

Minnesota climatology data supports a common rule of thumb that most of the snowpack disappears in the spring over a period of about 10 days. The question can be raised as to why this volume should be important if BMP facilities are generally designed for treating a runoff event lasting only 24 hours. That is, why would on average 1/10 of a snowmelt runoff volume going into a facility designed to treat a much larger volume be a problem? This is a very valid comment. Clearly, if the systems are built to store a large volume of rainfall runoff, there will be no problem. The difficulty arises when complicating factors in cold weather prevent the full storage volume for a pond, or infiltration capacity of an infiltration device, or conveyance for a diversion to be available during the period of time when they are designed to operate. Suddenly snowmelt could receive less than adequate treatment or by-pass any treatment whatsoever.

Various methods to deal with the conditions experienced in cold climate BMPs were suggested previously. But the question remains, should adaptations or sizing changes be part of the recommended criteria or simply recognize the need to change our approach to get the same treatment as the facility was intended to achieve during warm weather? Should we instead think in terms of the entire snowmelt volume over ten days and compare it with the daily value used for warm weather runoff events because the treatment levels will not be the same?

Information: Do not introduce flow into an infiltration area that originates in a potential stormwater hotspot or high traffic area where large amounts of salt are added. Flow from these source areas should be diverted away from infiltration systems.

Water quality credits for onsite snow management

Credits for snowmelt management should be considered when management decisions need to be made. For example, if there is an approved and enforceable snow management plan for a fully developed urban commercial site that dictates plowed snow will be hauled to a suitable on-site snow storage area (e.g., pervious soils, sump area sized to certain design specifications, spring clean-up plan), then the stormwater BMPs can be sized according to the baseline (rainfall runoff) criteria. However, if the same site merely plows the snow to a corner of a parking lot and lets it enter a storm sewer that empties to a nearby pond with a thick ice cover, then maybe the applicable SWPPP needs more attention.

Another opportunity to incorporate credits could be possible if it is presumed that the snowmelt sizing approach showed that the snowmelt water quality volume (Vwq) is greater than the rainfall runoff Vwq. If this is the case, certain measures could lead to a reduction in that volume to the point where it approached or equaled the rainfall Vwq. Credits such as considering subtracting out roof areas that drain to pervious surfaces could be applied to adjust the snowmelt volumes. If chloride loads are of particular concern, a credit could be given for residential streets that have a “reduced salt” covenant. The street area could be subtracted out of the snowmelt Vwq computation.

Perhaps the level of inclusion of a snow management plan should be a function of whether a community is covered under an NPDES MS4 permit. That is, are there exemptions that should be considered such as waiving snowmelt criteria for sites outside of MS4 jurisdictions? Another example might involve waiving snowmelt criteria for direct discharges to streams where the ratio of site drainage area to upstream drainage areas is less than some fraction (e.g., 5 percent). This argument would be loosely founded on the dilution principle, which has been previously identified as one of the limited management approaches for Cl, but might not send a positive message (that is, using dilution to solve a water quality problem).

Snow management plan guidelines

Perhaps the best approach for incorporating cold climate considerations into a community stormwater plan is through a “Snow Management Plan”. This plan could be implemented a number of different ways. The most obvious would be incorporation into the SWPPPs developed by MS4 communities or as part of a construction or industrial site permit. There currently are no requirements for snow management plans in state regulations. For large-scale operational agencies, such as Mn/DOT, it could be adopted in its standards of practice. The plan could also be part of an ordinance that a community requires be applied for specific types of land use, such as commercial or multi-family buildings.

This section in part addresses the need for guidance, but not fully. It does not, for example, provide fact sheets for small landscaping companies that plow snow at commercial facilities, which could be produced as part of the MS4 technical information assistance effort.

The following table provides guidelines for the preparation of a Snow Management Plan. Each of these categorical discussions also has a recommendation(s) on the proper approach.

BMP design modifications

Another option originally proposed in the CWP Cold Climate BMP Supplement (Caraco and Claytor, 1997) is to incorporate additional storage or treatment volume into typical designs. For example, the CWP proposed the addition of an extra 25 percent Extended Detention (ED) storage to ponds for winter use. This approach could also be accommodated under the seasonal designs presented in this chapter. It is clear that the problems associated with the collection, routing and treatment of snowmelt runoff will continue to occur unless the shortcomings of using our warm weather techniques to treat a cold weather problem are addressed.

Preliminary considerations for design sheets based on cold climate performance

Applicability of BMPs for Cold Climate

It is necessary to look at the list of BMPs and assess their applicability for cold climates. Details on specific BMP design and maintenance are part of individual BMP pages included in this Manual (see Stormwater Best Management Practices).

Adaptation concepts

Each of the design sheets for the BMPs addresses adaptations needed to properly operate in cold climates. Following in this section, however, are some select summary adaptations for some of the engineered systems.

Infiltration practices

Various options for use of infiltration are available for treating meltwater. Some of the installations are built below the frost-line (tree trenches, underground infiltration systems) and do not need further adaptation for the cold. Surface systems, however, do need some special consideration.

To maintain infiltration rates during cold weather period it is essential to have the infiltration practice free of standing water or ice. If drawdown times are slow, it is important to monitor leading up to frost and correcting the practice to improve drawdown time. This can be done by various methods including limiting inflow, under-drainage and surface disking. Even if the infiltration properties of an infiltration basin are marginal for melt, the storage available in the facility will provide some storage if it is dry entering the melt season. Routing the first highly soluble portions of melt to an infiltration facility provides the opportunity for soil treatment (filtration, adsorption, microbial activity) of these soluble pollutants as well as their removal based on infiltration alone.

Proprietary, sub-grade infiltration systems provide an alternative to standard surface based systems. These systems, in essence, provide an insulated location for pre-treated meltwater to be stored and slowly infiltrated, or simply filtered and drained away if ground water sensitivity is an issue. The insulating value of these systems adds to their appeal as low land consumption alternatives to ponds and surface infiltration basins.

For bioinfiltration basins, dry swales and tree trenches, plantings should be designed to mitigate damage from snow and ice removal and storage. Perennials and shrubs should be set back from the curb or other areas where snow piling is unavoidable. It is HIGHLY RECOMMENDED to choose plants that have been shown to be tolerant of higher chloride levels in soil and trees that can tolerate some salt spray.

Filtration and retention practices

In cold climates, stormwater filtering systems need to be modified to protect the systems from freezing and frost heaving. Physical design and operational considerations to keep in mind for filtration systems are included in the discussion for individual BMPs in this Manual (see Filtration).

An infiltration basin adapted for handling spring meltwater runoff would have an adaptation such as a sub-drain installed to dewater the basin of any water heading into the freeze-up. This drain can be closed just prior to meltwater inflow and during the non-winter seasons to allow infiltration to continue downward. Also note that a liner can be added if the need to protect local ground water from infiltrating meltwater is important. If this adaptation is made, the basin is no longer an infiltration system, but instead becomes a filtration system or dry pond.

Recent research by Kakuturu and Clark (2015) that looked into the effect that increased road salt level in filtration media has on the potential for nutrient leaching and premature failure of the filtration practice. In compost amended media, an increase in nutrient and other pollutants leaching from the media has been observed as sodium chloride levels increase. This research would suggest that care should be taken in siting filtration practices in locations where they are likely to receive snowmelt that has increased levels of road salt runoff to avoid nutrient loss into underdrains.

Note that although filtering systems are not as effective during the winter, they are often effective at treating storm events in areas where other BMPs are not practical, such as in highly urbanized regions. Thus, they may be a good design option, even if winter flows cannot be treated. It is also important to remember that these BMPs are designed for highly impervious areas. If the snow from the contributing areas is transported to another area, such as a pervious infiltration area, their performance during the winter season is less critical to obtain water quality goals.

Seasonal ponds

The difficulties of operating an effective storage and treatment pond in a cold climate were discussed previously. Problems exist with the thick ice cover (lack of reaeration, “impervious” cover for settling purposes, reduced storage volume) and under the ice (anaerobic conditions, resuspension of settled material, concentration of Cl and toxic material, dissolution and density stratification).

To overcome these difficulties, some seasonal adjustments can be made to account for winter conditions. The obvious need in this situation is to eliminate the effect of the ice layer. This layer can be up to several feet thick during a hard winter and can greatly reduce the availability of the designed storage volume. The result is usually a small amount of the initial melt diving under the ice in a somewhat pressurized manner forcing out water that might have sat stagnant all winter long. When the available capacity provided by limited uplift of the ice cover is filled, meltwater begins to flow over the top of the ice, which usually means outflow at the other end after very limited exposure to settling due to the “impervious” ice cover.

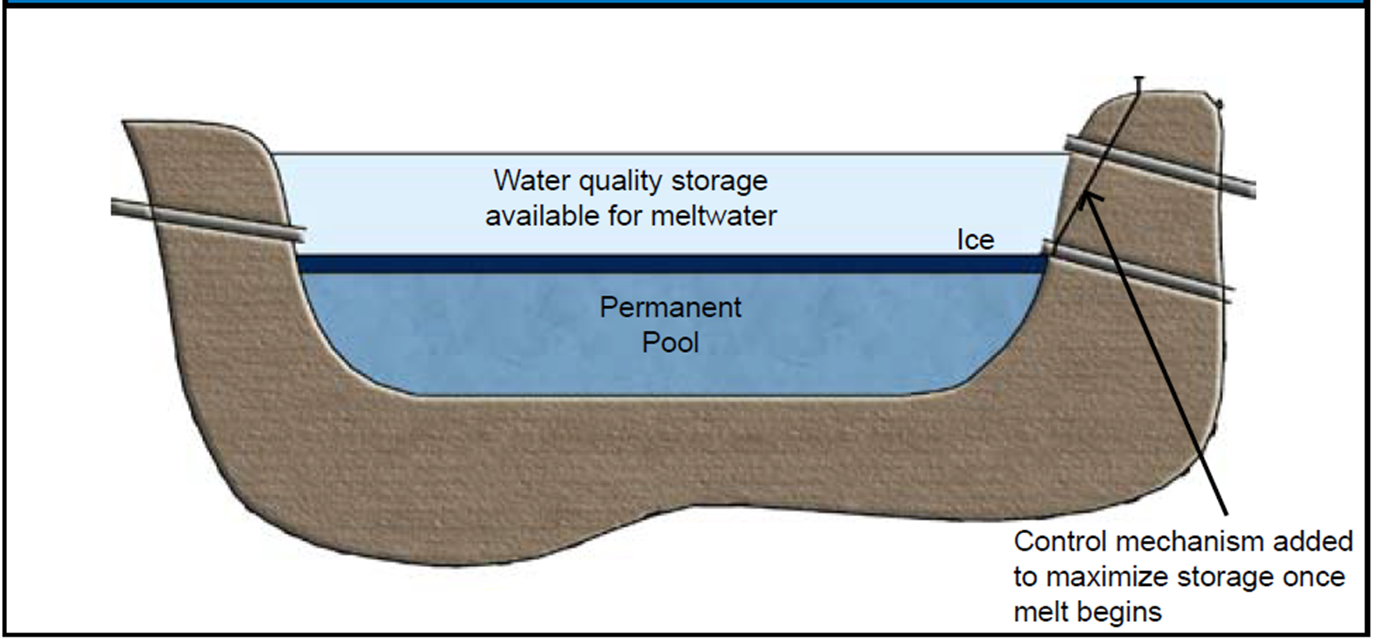

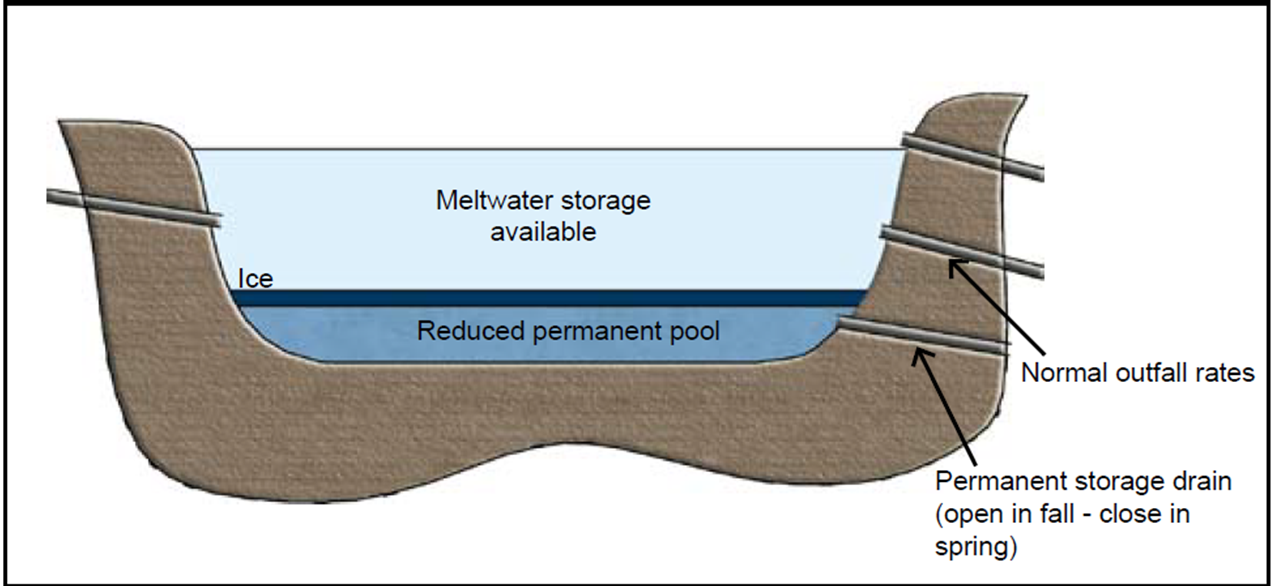

Minimizing the effect of the ice cover can be done passively through the design of surplus storage or actively through the management of water levels before ice has a chance to form and after meltwater inflow begins. In one adaptation, the normal design storage volumes are maintained, but a control mechanism (valve, weir, stop-log) is installed to reduce or even eliminate outflow for the normal water quality volume. This volume is then made available for meltwater, which can be held and slowly released. This approach provides for some settling time and could be used to capture high Cl flow for later slow release. The problems with under-ice build-up of anaerobic conditions and poor water quality will likely not be avoided under this adaptation.

A second adaptation involves a lowered permanent pool control and should be used when concern over the quality of water associated with a pond is paramount. This adaptation requires more active management, but will result in improved performance and fewer downstream water quality problems. This adaptation is especially recommended when sensitive receiving waters are a concern, or if additional treatment effectiveness is needed to achieve a TMDL requirement. Lowering the pool to a lower level will minimize the effect of an ice layer and maximize the storage available once the lower control is closed and the large spring melt occurs. The poor under-ice water quality concerns will be minimized. The “reclaimed” storage volume will equal most of the permanent pool and all of the water quality volume. The storage of all phases of the melt sequence means that solubles will be held, volume will be stored, and particulates will have a chance to both adsorb soluble pollutants and settle.

One caution for this system is that the permanent pool could completely freeze or possibly disappear entirely if the drawdown is complete. Since maintaining a healthy biological system is part of a successful detention system, it is recommended that the permanent pool not be drawn too far down such that total freeze-up or elimination occurs.

The importance of baseflow, inlet and outlet design in ponds

Baseflow

The problems that develop under ice could be overcome in situations where baseflow is sufficient to keep the water refreshed enough to avoid anaerobic conditions and pollutant build-up. An assessment (in most cases a visual estimate) of the rate of inflow from baseflow expected over a winter could form the basis for establishing a drawdown level for the permanent pool. That is, the volume could be designed to be replaced on a frequency determined to avoid the depletion of oxygen and keep pollutant levels below toxic levels. Information on the source and characteristics of the inflow can also be important to pond design levels.

The total absence or occurrence of intermittent baseflow should favor a very low permanent pool level if an active management approach can be pursued.

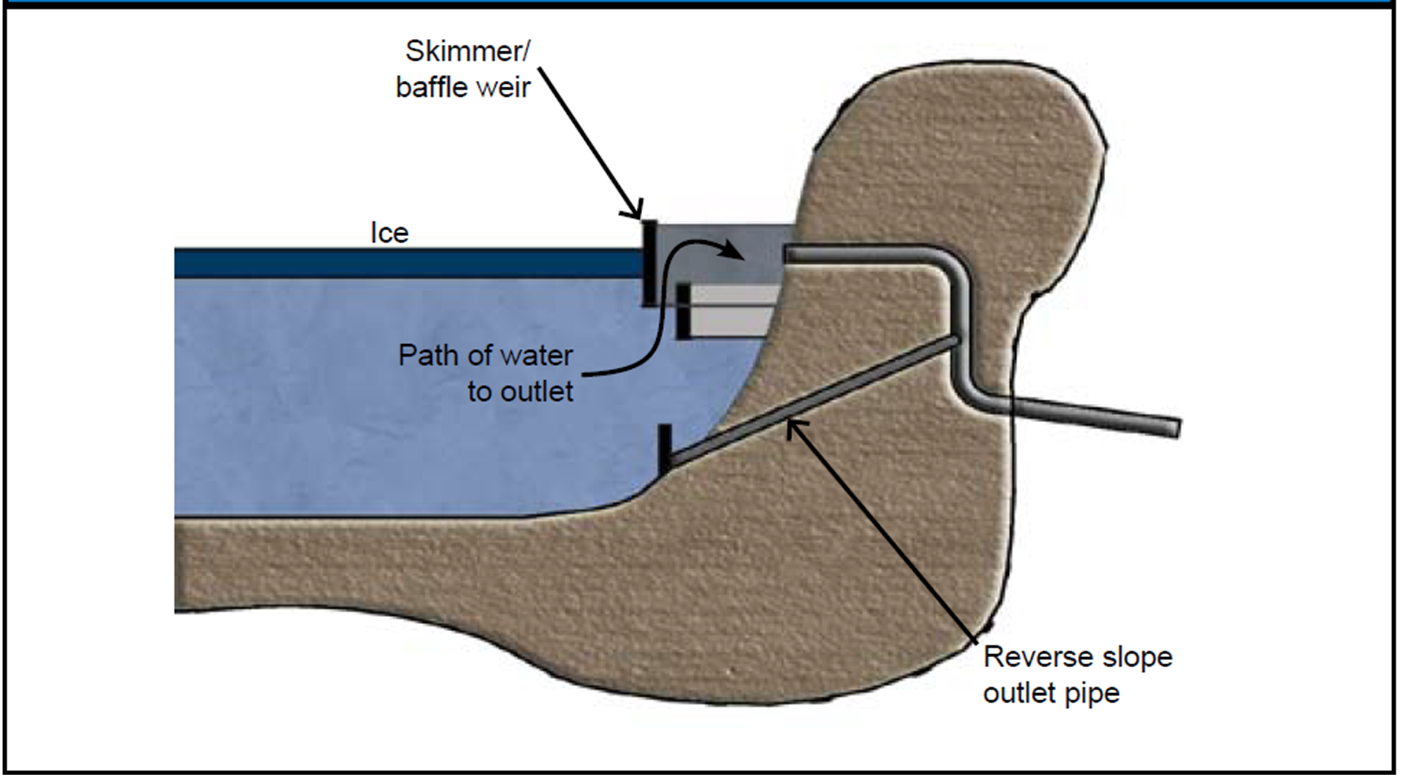

Inlet and outlet design

One of the biggest problems associated with proper pond operation during cold weather is the freezing and clogging of inlet and outlet pipes. Some basic outlet concepts should be mentioned. Perhaps as important as the layer of ice over the permanent pool is the blockage or hindrance of outflow from a pond because of a frozen outlet. There is a need to get water from under an ice layer to exit in a manner that does not cause splashing or gradual freezing of layer after layer of outflow. Drawing water from below the ice via a reverse sloped outlet pipe and installation of a skimmer device (baffle weir) that draws water from below the ice are two options.

Bioretention

Bioretention can be of marginal effectiveness for treating meltwater because of the dormancy of the vegetation during the cold season. However, the incorporation of some sump storage into the design of any bioretention system will provide an opportunity to route and collect meltwater and begin the filtration and infiltration processes. The only adaptation then that should be needed is the incorporation of some storage as part of the system. Once relatively “warm” meltwater begins to accumulate in a bioretention system, some downward migration will likely begin and the system will activate.

Vegetated conveyance

Routing runoff over pervious drainage surfaces is a management method to promote the infiltration of water and reduce runoff volumes. Previous discussion in this paper described both the promise and the problems associated with these systems in cold weather. In essence, any infiltration should be considered an extra benefit, but the systems should not be relied upon during winter conditions to operate as well as they do during warmer weather.

Snow and ice management

Dealing with the accumulation, removal and disposal of snow and ice is not a stand-alone BMP, but rather it encompasses many public works practices that potentially impact on the quantity and quality of meltwater runoff. Practices are as variable as the number of governmental public works departments and commercial maintenance companies providing services. Local snow removal does not usually involve collection and removal to a remote site. Rather, it is typically a matter of plowing to the side of the road or the far ends of the parking facility. Little thought is given to the fact that this snow will melt in the spring and flow into a receiving water or into a conveyance line that will flow to a receiving water.

Options for disposal of snow removed via neighborhood street and major roadway plowing are usually quite limited. The common Minnesota practice of pushing piles back from the paved surface as far as possible is encouraged. Research has shown that up to 90 percent of the pollution accumulated next to roadsides over the winter is deposited within about 25 feet of the road surface. Keeping the melt from this area off of the paved surface to the maximum extent possible is a positive water quality management strategy. Allowing it to soak into the ground is a good first step, followed by exposure of the melt to particulates in the roadside area so adsorption can occur.

Commercial and industrial areas that plow their parking and paved areas into big piles on top of the pavement could greatly improve the management of runoff if instead they dedicated a pervious area within their property for the snow. Even pushing the plowed snow up and over a curb onto a pervious grassed area will provide more treatment than simply allowing it to melt on a paved surface and run off into a storm sewer.

As mentioned previously, alternatives to NaCl for road salting are not currently feasible because of cost (high relative to NaCl) and secondary environmental effects (like high BOD). Until such alternatives become available, a wise-use ethic should be the goal of every salt user. Adaptations in equipment are always being evaluated by Mn/DOT, which continually updates its statewide fleet with improved equipment. Passing down its experience and knowledge on these improvements is an important role for Mn/DOT. Adequate driver training on application methods and monitoring of driver salt use are other approaches to wiser salt use.

There has been a shift in recent years by many public works departments to reduction in anti-skid sand and greater use of salt. This shift has been propelled by the high cost of removing sand from street surfaces and stormwater conveyance and treatment systems. If this trend continues, the adverse impact of salt on Minnesota’s receiving waters is likely to increase. As difficult as sand is to deal with, it is generally inert and can be easily removed. Salt is a conservative substance that readily migrates into soil, ground water, lakes and streams, causing problems at each step along the way. A continued state program to reduce use, keep storage areas covered, educate salt handlers and improve equipment is essential to keep salt loads down as we change to greater application percentages of pure salt.

Finally, reduction in overall salt use has always been perceived as competing with driver safety. The progress made in more effective salt application techniques will hopefully be adopted by all applicators and show how the two important goals of environmental protection and driver safety can co-exist. The ultimate approach must balance safety, economics, and environmental considerations.

High sediment load

The addition of sand as an anti-skid agent to roads and parking lots can lead to the accumulation of sand in conveyance systems and pond inlets, as well as the plugging of infiltration and filtration systems. Frequent inspection of these facilities is essential, particularly in the early spring when large amounts of sand are washed from paved surfaces into runoff conveyance and treatment systems. Examining the need for clean-out of conveyance lines, dredging of forebays and ponds, and debris removal from infiltration/filtration systems should be a part of an annual inspection and maintenance program.

Many of the newly available proprietary sediment removal devices are intended to be installed below the frostline and, therefore, operate as designed under all weather conditions. These systems come with many different design approaches, but as a group they provide a very good method of pre-treating inflow into primary runoff treatment devices during the winter and spring runoff seasons.

Secondary practices

There are some BMPs that are not generally recommended for water quantity or quality improvement because they are not as effective as other available techniques. There are situations, however, when these less used BMPs could have a possible cold climate role. One example of this is the use of dry detention ponds. These ponds have a limited long-term water quality benefit, although there is some benefit from the fact that a portion of the stormwater infiltrates while it awaits outletting. A secondary benefit could be achieved by routing overflow meltwater from a non-functioning practice into a dry detention pond to obtain even a small amount of infiltration and settling.